We Don’t Celebrate the Boring Years of Social Movements—But We Should

Julia Baird on the Long, Hard Work of Activism

In a corner of a lower floor in the Museum of London stand several glass cases that hold relics of the suffragette movement. In the rows of inert objects you can glimpse the force of the protestors’ actions, their anger, and their daring: large, broad brown leather belts with thick chains that stretched through dresses to railings, and axes that slashed through paintings and smashed windows. It is these signs of guerrilla combat that are the most striking. The axes are slender, almost delicate. And next to them are memorial brooches featuring axes on backgrounds of flowered material; you can imagine them being pinned to bosoms at meetings—“Nice work at the National Gallery, love.” Slash, destroy, pin on a pretty brooch.

Yet what is also significant is what is not displayed in these boxes, not pinned and preserved as emblems of combat: the ephemera of the grinding middle years, the time after the initial excitement of starting a movement and before the eventual triumph of reform. Absent are the memoranda from the decades before the public eruptions, from the decades of slog and sweat and boredom; the times of endless meetings and arguments between the suffragettes (militant, violent, female-only protesters), suffragists (peaceful campaigners, among whom men were included), and others who wanted to improve the lot of women, all eventually muddling together and gathering behind the banner of VOTES FOR WOMEN; the years when it was a battle to get anyone to turn up, when the air was thick with the smoke of social disapproval, when individual agitation was undermined by internal bickering, when the strength of opposition or the glacial pace of change made dissent seem futile, or when a handful turned up to protest only to find it seemed like no one cared.

We don’t celebrate the boring years of social movements, only the daring actions and headlines, the eventual victory and acclaim. We hunt for evidence of the headiness of solidarity, not the interminable minutes of, say, a hundred women’s groups, laced with passive aggression and conflict along with a thirst for change. But the history of women’s liberation has not been just bonnets bobbing behind banners—remembering that the first official “wave” was about suffrage for white women—or Indigenous women like Faith Bandler successfully campaigning for the vote in the lead-up to the 1967 referendum in Australia, or the brilliant activism of African American women during the civil rights movement, or an ocean of pink pussyhats (which were criticized for excluding transgender women and women of color) flooding the streets of Washington, DC, during the 2017 Women’s March, or the lava flow of #MeToo stories after the rapacious film mogul Harvey Weinstein was finally outed as a predator.

It’s not just the story of eventual, roaring, undergarment-tearing success, but also the story of a thousand “failures”—of women who continued to speak when no one was listening, bills had been defeated, the numbers were against them, and they’d been told to give up; of women who burned with the fervor of hope for equality only to be dismissed as insane, troubled, hysterical, or angry by their entire neighborhood, family, or community.

It’s the story of women who kept marching, through the long years of ignorance, in the hope that others might hear their footfalls and join in; who knew that this marching really meant making countless phone calls, or sitting by a printer, photocopier, or even fax machine for a week, or some other dull, repetitive, unglamorous work, or painting signs, or making large pots of tea. None of this was failure—it was persistence—even if it felt like failure to those in the thick of it. It’s a feeling I am very familiar with.

*

It is difficult to say exactly why for two decades I kept nine boxes stuffed with clippings, newsletters, minutes, and court transcripts from work I did at university. They traveled from a tiny studio apartment in Sydney’s inner city, to musty homes on sea cliffs, into storage for years while I lived in America, and back again to perch on crowded shelves in a little cottage sitting on a peninsula between the harbor and the sea.

They followed me everywhere, these large inchoate cardboard cubes, cracking at the corners and bursting with paper. They were untidy and unresolved. They bothered me; but I could not throw them out. I could not entirely figure out why. I think I wanted to think that the tale they told mattered.

Why do we keep these fragments, why do we honor these moments of our younger selves?

I guess I hoped that one day I would have a story to recount about my twenties, a period lived on inner-city streets and sandy beaches and punctuated by exams, a strange crew of delightful albeit temporary boyfriends, explosive parties, and trips to India. Throughout that time, as I was falling in and out of love, cramming for law exams, and repairing boots when soles wore out on dance floors, I was trying to challenge the Sydney Anglican (Episcopalian, or Church of England) Church’s oppression of women, a church I had begun attending with my family when I was ten, and which I have struggled to remain in ever since I began to question their views on women when I was a teenager.

This was a church that still told women to be silent, to not speak of the Bible when men were present, to submit to male authority. A church that tried to rebrand and prettify patriarchy, to pretend it was not ancient but countercultural, resisting the sinful pull of modern feminism. A church many of my friends had fled. For those who stayed, there was comfort and community but often a cost—one uniquely talented friend told me that when she accepted her husband’s proposal she had somehow prayed away her sin of ambition.

The boxes dared me to remember.

What is it about a youthful bout of activism that stays with you so long, no matter if you succeed or, in my case, fail spectacularly? Why do we keep these fragments, why do we honor these moments of our younger selves? Is it the memory of hope? Is it the belief that even this history, piecemeal and peripheral, matters? What makes a story worth remembering? Should we collect only remnants of success and sweetness, or also pay homage to foul odors and failure? Is the sweetness simply in the achievement, or more in the striving, and the dreams?

I was a mother of two children in primary school by the time I began going through my boxes. I was tempted to just throw the lot out, but was also conscious of how much of my early self was stuffed in there—all the foolishness and earnestness and taking-myself-seriously. I tried to skip through them quickly, but kept getting snagged on snippets.

There is a certain poetry to campaigning for reform: circling an institution, blowing trumpets and occasional raspberries, and demanding to be heard. And what I realized was that here, in my own life, was proof that what we often miss in many sweeping histories of protest—of, say, “waves” of women’s protests—is an account of the decades in between, the middle phases of drawn-out campaigns, the years when often all seems futile and lost, and yet people still persist.

That’s not just the story of feminism; it’s the story of anyone who has sat through PTA or city council meetings, tried to clean up local football fields or stormwater outflows, worked to improve community sport or foster art, or cared about something bigger than themselves, and who found their good intentions led them into a quagmire of boring meetings and years of crushing inaction before things, finally, shifted or changed. It’s also the story of those who tried, but never saw anything change, not in their lifetimes. And it’s about allowing ourselves to try, and honoring ourselves for caring, striving, and giving a damn.

__________________________________

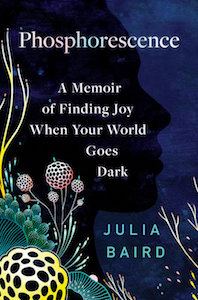

Excerpted from Phosphorescence: A Memoir of Finding Joy When Your World Goes Dark. Used with the permission of the publisher, Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Julia Baird

Julia Baird is a journalist, broadcaster, and author based in Sydney, Australia. She is a columnist for the International New York Times and host of The Drum on ABC TV (Australia). Her writing has appeared in Newsweek, The New York Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Monthly, and Harper’s Bazaar. She has a Ph.D. in history from the University of Sydney. In 2005, Baird was a fellow at the Joan Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University.