Watching the Films of Weimar Germany to Understand Our Increasingly Fascistic Present

“My dive into Weimar Germany taught me that authoritarianism doesn’t always follow a linear path.”

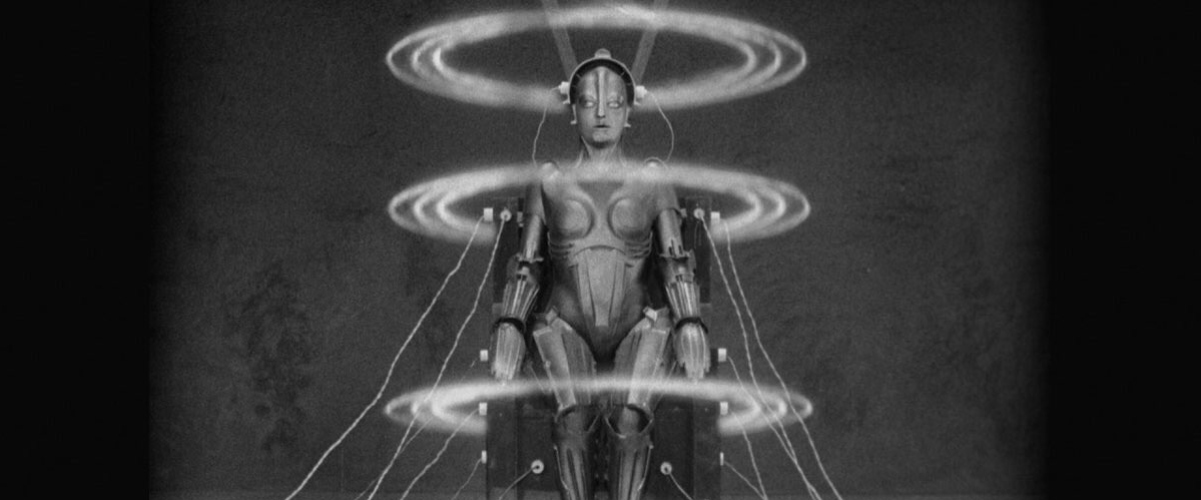

Near the climax of Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi epic Metropolis, an android in disguise delivers an incendiary speech to a crowd of exploited workers. “You have waited long enough!” she (it?) tells them. “Your time has come—!” To us, the viewers, the robot appears unhinged, her arms flailing wildly and her eyes opened unsettlingly wide. The mob, however, is emboldened by their leader’s fervor. They spill into the streets, plow through barricades, climb walls, and push their way up a great staircase to the city’s power center, the Heart Machine.

I’ve seen Metropolis at least a half dozen times, and this sequence is lodged in my memory—a mental benchmark for images of spectacular chaos and crushing waves of humanity. So when I turned on CNN two Januarys ago to watch thousands of indignant rioters fight their way up the steps to the US Capitol, my movie-addled brain couldn’t help but think, “At least the robot had a point.”

*

Like a lot of people, I spent the spring of 2020 cycling through a succession of new hobbies that I hoped might distract me from the seemingly imminent collapse of the American project. YouTube yoga. Sourdough. Getting drunk on White Claws and logging onto Facebook to call my high school gym teacher a fascist. (In my defense, Coach —— is, indeed, a fascist.) None lasted. I threw out my back struggling through a yoga lesson cruelly labeled “beginner,” my sourdough starter died cold and alone in the depths of the fridge, and I was no longer welcome on Facebook after somebody (Coach ——? my MAGA cousin in Ohio?) snitched to Zuckerberg that my account was under a name other than the one on my state-issued ID.

Even as each of these anxiety-induced diversions fell by the wayside, there was one interest that stuck: the movies of Weimar Germany. I’m an adjunct professor of film history, so this development wasn’t completely random, but it was an era I didn’t have much knowledge of, let alone expertise. For reasons I didn’t quite understand, the jagged angles and macabre stories of Expressionist directors like F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang were among the few things that could keep me from obsessive doomscrolling. I was still drinking too many White Claws, but doing so while working my way through G.W. Pabst’s back catalog felt healthier than picking online fights with people I barely knew.

Given the pandemic windfall of free time, it wasn’t long before I was reading books with titles like Film Front Weimar and Weimar Cinema and After. I read, I watched, and I built up a very healthy Duolingo streak. Looking back, I think these movies and the lives of the people who made them offered a window into another moment of social instability and political turmoil.

The Weimar Republic was a brief, volatile interlude of democracy between the abdication of the Kaiser in the wake of Germany’s 1918 defeat in World War I and the Nazi capture of power in 1933, and the echoes between then and COVID-era America are certainly there if you’re looking for them: The looming threat of authoritarianism. Ideological battles spilling into the streets. Right-wing politicians drawing ever sharper lines between the patriots who belong and the racial, sexual, and political others who dilute the purity of the body politic. It wasn’t that I was expecting these movies to provide a step-by-step guide for fending off fascism, but I think I was looking for a lens to make the present a little more comprehensible. That lens turned out to be surprisingly literal, and it was attached to an antique Stachow-Filmer camera.

After a few months of aimless research, I decided that I should try to do something with all the stuff I was learning from century-old movies and books about long-dead German auteurs. By turning my interest into a project, I could give myself permission to indulge my new obsession. “Why no, Super-Ego. I haven’t taken any steps to publish my dissertation. And yes, I’m five years out of grad school and still languishing in adjunct hell. But could I interest you in a podcast?”

These movies and the lives of the people who made them offered a window into another moment of social instability and political turmoil.

It’s maybe appropriate, then, that as I tried to keep my psychic apparatus in balance, I read From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of German Film by the Frankfurt-born film theorist Siegfried Kracauer. In it, Kracauer argues that film is unique among the arts because since its birth in the late 19th century, its intended audience wasn’t some rarefied class of elites. Movies have always been aimed at the masses—“the anonymous multitude.” The films that resonate with their audience, then, are effectively the dreams and fantasies of an entire culture.

Through his midcentury blend of Marxism and Freudianism, Kracauer put forward the idea that Weimar cinema expressed a fundamentally and intrinsically German desire to be dominated, even hypnotized, by a charismatic leader. Metropolis’s rabblerousing robot is a clear example, but there are others. In The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the eponymous doctor employs mysterious powers to create a sleepwalking hitman who has no choice but to kill on his master’s behalf. Dr. Mabuse—the criminal mastermind of two Fritz Lang classics—uses mind control to force his adversaries to take their own lives. The golem in The Golem is, well, a golem. In all these stories of control and submission, Kracauer saw premonitions of the Führer.

It’s an enticingly simple narrative—too simple for most contemporary scholars. Kracauer was writing from New York in the late 1940s, using the clarity of hindsight to process his home country’s descent into fascism, and he tends to dwell on films that support his thesis and gloss over those that don’t. Whether or not the works he highlighted are representative of their era, Kracauer’s influence helped to surface their subtext and enshrine them in the canon of world cinema.

So while it’s a stretch to say that Weimar film writ large was a symptom of some national psychopathology, From Caligari to Hitler helped to ensure that the Weimar films still watched today disproportionately resonate with the emotional and political harmonics of the time and place they were made. Their commentary may be explicit, as when Lang subtitled Part I of Dr. Mabuse the Gambler—a movie filled with urban shootouts and economic chaos—“A Picture of Our Time,” or implicit, as in the antisemitism suggested by the grotesque hook nose of Count Orlok, the vampire in Nosferatu, himself an Eastern European invader with designs on the blood of Aryans.

Kracauer recognized that films aren’t generally made for posterity. They’re commercial products whose makers want to find a contemporary audience. When Pabst directed Kameradschaft—his story of German miners who put their lives on the line to rescue their imperiled French comrades, national animosities be damned—he wasn’t dreaming that his movie might one day be tapped to join the Criterion Collection.

He was looking around at the Germany of 1931, when the wounds of the First World War were still fresh and hypernationalist Nazi chauvinism was on the rise. He made a movie that spoke to his moment—to Weimar audiences—and insisted that a German miner and a French miner share more in common than either does with a mine owner, an army general, or a Führer on their own side of the border. It was a call for solidarity in a time of jingoism that’s made all the more poignant by our knowledge that the two countries would be at war again in under a decade. These are historical connections I likely wouldn’t have made if I hadn’t spent my pandemic reading books like The Films of G.W. Pabst: An Extraterritorial Cinema, and despite that book’s eye-glazing title, there was something thrilling about how it helped me imagine my way, however imperfectly, into some approximation of how a Berlin moviegoer may have experienced Kameradschaft nine decades ago.

Kracauer put forward the idea that Weimar cinema expressed a fundamentally and intrinsically German desire to be dominated, even hypnotized, by a charismatic leader.

The past, as novelist L.P. Hartley put it, is a foreign country, which I suppose is doubly true if the country whose past you’re examining is foreign to you. I first saw Kameradschaft before I knew much about the finer points of Franco-German relations during the interwar years. The film concludes with a celebration, as the miners from each side of the border come together to affirm the new bonds that they’d forged deep underground. First, a Frenchmen gives a speech, and then a German, played masterfully by Fritz Kampers, replies:

I couldn’t understand what our French comrade just said. But we all understand what he meant. Because it doesn’t matter if you’re German or French. We’re all workers, and a miner is a miner. But why do we only stick together when we’re in trouble? Are we to sit idly by till they fill us with so much hatred that we shoot each other down in another war? The coal belongs to us all… whether we shovel it on this side or the other. And if those above us can’t come to an agreement, we’ll stick together, because we belong together!

Even though I didn’t know much of the context yet, the speech gave me chills. Though I’ve been pumped full of enough postmodern theory that I hesitate to call this or any sentiment “universal,” this rejection of tribal animus sure as hell felt relevant to the Trump era. They’re sending their rapists. The Muslim ban. Build the wall. Shithole countries. Chinese flu. Stand back and stand by. The end of Kameradschaft is sometimes criticized as corny or ham-fisted. Watch it and come to your own conclusions. But for me, at the time I first encountered it, it felt like a celluloid bridge between now and then, here and there, present and past.

*

2020 became 2021, 2021 became 2022, and I hadn’t recorded a minute of audio. It didn’t feel like I understood enough to speak with any kind of authority. I’d be happily working on an episode script, then I’d run into some question at the edge of my knowledge. If cameras in the early sound era were stationary, I’d ask myself, then how was the camerawork in Westfront 1918’s battle scenes so dynamic?

I’d scour the internet until I found my answer: Ah, of course… they shot the scenes like it was a silent film and dubbed the sound effects in later. It was an afternoon of research that would ultimately add up to maybe 15 seconds of airtime. My therapist asked why that detail mattered to me. Was this information important to the story I was telling? Did I imagine that if I got a fact wrong, some Endowed Chair of Weimar Cinema would expose me as a fraud? Was I afraid to actually finish the project? I didn’t know.

As the work dragged on, these movies and the people who made them became a constant household presence. Thankfully, my wife, Laura, was willing to accommodate me. We joked about how Lil Dagover, the female lead in Caligari, has a name that perfectly positions her for a crossover career in hip hop. Laura tolerated my new celebrity crush: Louise Brooks, the libertine icon of Jazz Age Berlin who died at age 78, two months before I was born. On a trip upstate, Laura called me over to the hammock where she was peeking through a crack in the canvas, her face stiff with mock rigor mortis, à la the undead Count Orlok asleep in his coffin. They say every marriage is a culture, and ours was looking ever more Teutonic.

This rejection of tribal animus sure as hell felt relevant to the Trump era.

The more invested I became in these films, the more they—and the era that produced them—became my mental frame of reference. One-hundred-year-old movies and 21st-century discourse increasingly collapsed into one another. The Blue Angel: Professor Rath is pushed out of his job for falling in love with a cabaret singer. The precarity of the academic labor force is truly unconscionable. Die Nibelungen: A romanticized myth that distorts Germany’s past for nationalist ends? I bet Fritz Lang has opinions about the 1619 Project. Metropolis: The best way to stop a mad scientist tech bro from tearing society apart is to throw him off a very tall building.

Early last summer, I marked August 17th on my calendar. “Podcast launch day.” Time to touch grass.

*

October 2022, a few weeks before Election Day. My six-episode podcast series was out in the world. I felt good about it. Criterion said nice things. I could take a breath, relax, and, yeah, brag a little bit.

For my birthday, Laura got us tickets to Company XIV’s Cocktail Magique. In the American imagination, there are, I think, two archetypal cabarets: Nicole Kidman’s Moulin Rouge and Liza Minelli’s Kit Kat Klub. Despite the French-inflected name, Cocktail Magique leans toward the latter. Gender is gleefully bent. The MC presides over the increasingly debauched festivities with a sense of camp that would impress Joel Grey. A woman in impossibly high heels steps from the top of one upright wine bottle to the next, her hair fashioned into the black bob helmet of Sally Bowles (or is it Louise Brooks?).

On the subway ride home, Laura and I discover we’d had the same thought during the show, perhaps because I’d invited those Weimar ghosts into our home. According to the New York Times, Nate Silver, and Kevin McCarthy, the American brownshirts were poised to decisively seize both houses of Congress, riding a wave of economic rage, racial animus, and a neanderthal disgust at “gender ideology.” And here we were, playing our roles as if scripted by Tucker Carlson: her an organizer with the teachers’ union and me a humanities professor, tossing back our drinks at a self-consciously louche Brooklyn cabaret as the Right clawed its way back into power.

The threat may have abated, but it hasn’t disappeared.

Of course, the New York Times, Nate Silver, and Kevin McCarthy got it wrong. I did, too. Some of the scariest candidates lost, albeit narrowly. The post-MAGA reprieve continues, hopefully indefinitely. When you spend a few years mentally living in another time and place, watching the faces of real people who really experienced the collapse of democracy flicker across your screen, your mind starts drawing connections with the world around you. Some are valid, and some aren’t.

But my dive into Weimar Germany taught me that authoritarianism doesn’t always follow a linear path. Like any other political sensibility, it can ebb and flow. The threat may have abated, but it hasn’t disappeared. The House of Representatives is at the mercy of a fascist caucus that is prepared to tank the economy to achieve its ends. Trump is ready for a rematch, and the Florida governor challenging him is no less noxious.

Lately, I’ve been reading a lot about Italy’s Years of Lead, the wave of political violence that rocked the country from the late 1960s into the 80s as submerged wounds from the Mussolini era resurfaced. This stretch coincided with the rise of the Giallo film—a genre of highly stylized crime thrillers from directors like Mario Bava and Dario Argento that, according to some critics, reflected the tensions erupting in Italian society. I think a second season is starting to come together. Fingers crossed that this one is wholly irrelevant to our here and now.

Travis Mushett

Travis Mushett is a New York-based writer and thing-maker. He hosts The Haunted Screen, a narrative history podcast about international film movements that's been praised by the Criterion Collection for how it "shapes swaths of cinema's past into engaging, character-driven stories." In the name of brand consistency, his Substack newsletter is also called The Haunted Screen. Travis holds a PhD from Columbia University and teaches film and media history at Fordham University and Marymount Manhattan College.