Warts and All: In Praise of the Unauthorized Biography

Brendan O’Meara Offers Some Advice to Writers and Journalists Seeking to Go Beyond the Sanitized

When first you hear the words “unauthorized biography,” the knee-jerk reaction is of something unsavory, Grima Wormtongue at the shoulder of the corrupted Theodin, King of the Rohirrim in The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Unauthorized connotes a sneakiness, perhaps even tabloid trash, but all it is is pure journalism free of editorial control of the book’s central figure or figures.

As Kitty Kelley, the author of several biographies on subjects like Nancy Reagan and Oprah Winfrey, wrote in an article for The American Scholar, “Even after all these years I’m still not comfortable with the term unauthorized. Because it sounds so nefarious, almost as if it involves breaking and entering.”

There’s a distinction to be made between collaboration and cooperation. Collaborating is either ghost writing or co-writing a book where the central figure has final say, a way of sanitizing the text. Think of Open by Andre Agassi, Shoe Dog by Phil Knight, or Spare by Prince Harry, all ghost written by J.R. Moehringer.

Unauthorized connotes a sneakiness, perhaps even tabloid trash, but all it is is pure journalism free of editorial control of the book’s central figure or figures.

Cooperation is when the central figures at least grant you interviews, though this is not always a guarantee. It’s preferred that they cooperate, but there’s a good chance that the more famous they are, the less likely they’ll participate. Nevertheless you proceed.

The biographies of Bill Belichick, Aaron Rodgers, and Derek Jeter by Ian O’Connor are unauthorized. As is Madeleine Blais’s biography on Alice Marble and the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies on J. Robert Oppenheimber, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, and Margaret Fuller. In the words of O’Connor on The Creative Nonfiction Podcast, unauthorized is his “cup of tea,” not working as part of a collaboration.

This is, admittedly, more challenging. If they are public figures (and let’s face it, if they are worthy of biography, they most likely are and are thus fair game), it’s a matter of tracking down the people who knew or know them best.

This is journalism. But if we’re to call back to a few paragraphs ago when Kelley said it can feel akin to breaking and entering, there are ways to ensure it doesn’t feel like that. You must be forthright. You must be fair.

Your first call or email is always to the central figure, or the surviving standard bearer of the central figure. Reason being you don’t want to look like a raccoon burrowing through people’s trash under darkness of a new moon. Should they reject participating, you proceed to building out a roster of people who can then start rounding out the whole.

Ultimately, what you’re left with is a truer account of a person’s life, one not airbrushed by their public relations team, one not bleached of anything unsavory. Because it’s these unsavory details that make us human. Without them, we’re left with tripe, something unrelatable and unattainable, worst of all: untrue.

*

Unauthorized biography is the more challenging road filled with potholes and road blocks. Nobody said it would be easy. In Jeff Pearlman’s biography on Bo Jackson, Jackson tells Pearlman at the outset that he wouldn’t participate and wished him luck. The worry is when the central figure begins to run interference and telling people not to speak on the record. What this necessitates is more rigor, more time on the phone, more miles logged in the car, more shitty biscuits eaten in coach.

What’s the best way to find people? It’s both simple and difficult. Online phone books like Fast People Search often provide leads to numbers and emails, but they are just as often dead or wrong. White Pages is a paid service and gives more reliable numbers, but they, too, can be inaccurate. Cross-reference the two sites gives you a shot.

Classmates.com is a repository of yearbook scans, which can give you a roster of hundreds of people worth calling. Browsing Facebook for organizers of class reunions is an apt way to find a master node that can connect you to a vast network of people willing to talk. Then it is up to you to pick up the phone and make the calls.

Which—can I be real?—even as a journalist, is terrifying and anxiety inducing to the point of indigestion. What helped me when reporting on The Front Runner was having a script on my monitor. It said:

Hello XXX, my name is Brendan O’Meara and I’m a journalist and author based out of Eugene, OR and I’m under contract with an imprint of HarperCollins to write a new biography on the life of Steve Prefontaine. It’s my understanding you were teammates, and I’d love to get a sense of what you remember about your time with Steve. No detail is too small. I greatly appreciate your time and I look forward to hearing back from you.

It’s these unsavory details that make us human. Without them, we’re left with tripe, something unrelatable and unattainable, worst of all: untrue.

To quell some of the nerves around this, especially since trust in journalists and journalism is somewhere north of zero and less than one, is, to quote Jared Sullivan, the author of Valley So Low, from his appearance on The Creative Nonfiction Podcast, is to see these reporting calls as asking for help. It doesn’t feel as extractive and makes the person settle in and feel more of an accomplice in getting the story right. It also has the effect of defanging the conversation.

*

David Maraniss, author of several biographies including his more recent title Path Lit by Lightning, has a four-pronged approach to biography. One, go there, wherever there is. Two, interview as many people as possible. Three, get the documents. Four, most importantly in unauthorized biography, break through the mythology.

And this is the crux of a more measured, journalistic approach. So many people worthy of biographical treatment have reached, by and large, mythic status, even legend.

Jonathan Eig, while researching his Pulitzer Prize-winning King: A Life, said in a New York Times interview, “We’d turned him into a monument and a national holiday and lost sight of his humanity. So I really wanted to write a more intimate book.”

Citing Kelley again, she wrote, “To quote JFK, ‘The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived, and dishonest. But the myth—persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.’”

Unauthorized biography done well burrows below the mythology and restores their personhood. Working as part of a collaboration often scrubs the more human elements from the story, those moments that might be unflattering are the moments that remind people that these mythic figures of our imagination are, in fact, flawed humans, just like you and me. Depending on the person, we may even like them more for it. Contrary to what they might think, they don’t own their history.

And it’s only by finding names deep in the roster of record that the less rigorous ignored, that we begin to triangulate a portrait that is all the more beautiful for its blemishes.

You’ll excuse me for quoting Kelley again, but her insights into this form bears repeating. “Still, I believe that the best way to tell a life story is from the outside looking in, and so I choose to write with my nose pressed against the window rather than kneel inside for spoon-feedings.”

The astute reader appreciates the difference.

__________________________________

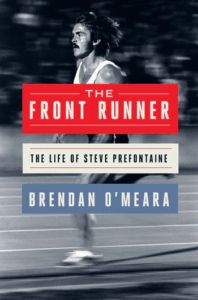

The Front Runner: The Life of Steve Prefontaine by Brendan O’Meara is available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Brendan O’Meara

Brendan O’Meara is a journalist and author of The Front Runner: The Life of Steve Prefontaine (Mariner Books). Since 2013, he has hosted The Creative Nonfiction Podcast where he talks to writers about the art and craft of telling true stories. You can follow him on Instagram @creativenonfictionpodcast and subscribe to his two monthly newsletters, Rage Against the Algorithm and Pitch Club.