“War Plants Paper Flowers.” New Ukrainian Poetry by Iya Kiva, Ostap Slyvynsky, and Halyna Kruk

“At every step one could wind up in someone else’s poem.”

Poets have long defined Ukraine. In the year since Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukrainian poets have helped to share with the world not only the country’s rich textual tradition, but also what is worth fighting for: children’s futures, self determination, the “freedom to rest in a land of love,” as Iya Kiva wrote in a poem from the brutal spring of 2022:

we’ve packed a contraband humanitarian aid kit of war songs

and shipped it to Europe America India and China

paving the silk road with great Ukrainian literature

what have you got there, brothers—they ask at the borders—

silence dressed up in cyrillic letters

the sacred fire of the candlelight letter “ї”

our and your freedom to rest in a land of love

Scholars and translators of Ukrainian have acknowledged receipt of this aid kit, mobilizing to render Ukrainian poetry into a variety of languages.

To mark the passage of a year since the full-scale invasion, a year of Ukraine’s battle for independence, we are sharing the work of three Ukrainian poets. The poems by Iya Kiva and Halyna Kruk were written during the past year and are part of forthcoming collections, which I’ve translated together with Yuliya Ilchuk. The poems by Ostap Slyvynsky were written shortly before the February 2022 invasion. “Amber” is a joint translation that emerged from a poetry workshop at the recent virtual gathering of the American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages (AATSEEL).

–Amelia Glaser, UC San Diego

*

Two poems by Iya Kiva

memory dries like grass in summer’s garden

(air raids in most regions of Ukraine)

i turn the key in a broken lock

and the door to the past closes

somewhere in my inner east, space

is overgrown with danger weeds, somewhere and nowhere

a favorite childhood hobgoblin falls in the slag heap

(attention everyone to a shelter)

what do you feel now

they ask in almost every interview

Creaky krieg

throat cut with a bottle shank—shape of a Donbass rose

glass shards of a stolen youth in your hands and feet

these pretty metaphors are literature’s crooked mirror

I can’t remember

what I feel

(attention the air raid is going off)

and I’m trying to escape the parentheses

***

on the unmarked graves of our lives

war plants paper flowers

The suffocating blossom of frozen time

its eyelid pages cut with a death knife

the borders of light and dark flatten into a platter of laughter

over the old fable about good defeating evil

cozy world, your unwanted children

have lost the ability to hear anything but atonal music

lost the ability to spell the word “love” out of legos

lost the ability to look their future in the face

with trusting eyes empty as their parents’ houses

long as the road to safety, this epic tale of freedom

smeared in the blood of the new abc’s of history

where every word must be looked up in the dictionary

and our mouths fill with the body of the earth

that’s caught like a noble beast in a trap of courage

pushing with all its weight our immobilized tongues

toward a mute boat amid rocks of pointless testimony

I’ve seen these deserted shores of justice before

I’ve seen these keys before in the beaks of birds of passage

Translated from the Ukrainian by Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk

***

Amber

by Ostap Slyvynsky

Tell me, was that a joke? I dug

all night long, like you ordered me to,

the mice mocked me.

I seemed to see, on the other side

how the leaves were warming,

children readied for school,

dressed in starched collars,

how they double-checked that the iron was off,

watered the petunias with a tin

watering can.

And I could swear I heard

a heart beating through the clay. So, did I

intrude on hope for nothing?

Turned the earth for nothing, digging

for one bright line?

Explain this to me, as I stand here,

staring at my own palm,

where, under the very ring finger,

that rubbed against the shovel’s handle,

a grain of amber is ripening,

like a lamp, briefly lit

in some purgatory of mine

by my own hand.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vitaly Chernetsky, Sibelan Forrester, Amelia Glaser, Olga Hasty, Yuliya Ilchuk, Roman Ivashkiv, Iryna Kovalchuk

Last Letter

by Ostap Slyvynsky

You leave, shutting the darkness like a folding table.

How much clothing we’ve ravaged!

How many yachts sailed into our waters, how many

fireworks there were and bodies! How we slammed

into the sleepy crowd, armed with an accordion!

But a thousand quiet Tuesdays are worth an hour’s weeping.

Sometime a neighbor will stop your hot clock hand.

Children will make their hideouts on the open

side of the rain, and there won’t be a minute without their knocking and laughter.

You’ll celebrate the evening arrivals,

you’ll sink into the plush carpet, full of sparks;

your quiet magnet will sparkle, while a wet hand

knocks at the door. And all this will happen as though you’d

long been praying to the beautiful Sunday gods.

Stay with me the whole sleepless night,

the whole night of watchfires.

If I should stumble, hold me

by my pale foot.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Amelia Glaser

***

bifurcation point

by Halyna Kruk

in wartime Lviv, (they’ll write later)

there was a strong literary milieu,

most likely, they published as a group (like those modernists in “Mytusa”)

or gathered for readings (because what else would poets do in wartime!)

there were so many there:

the internally-displaced and the externally-dysfunctional

like briefly during the first world war, and the second, on their way through Europe,

before the iron curtain tore the modern world’s voluptuous naked body

wide open

back then it was more about Prague and Podebrady, Warsaw and Munich,

but this time they’ll talk about Warsaw and Lviv,

Chernivtsi and Uzhhorod, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil,

where there were so many of those poets it seemed

at every step one could wind up in someone else’s poem

in nightmares, in history, in the news, on the floor where you share a mattress,

under a single borrowed patchwork quilt

(what a perfect metaphor for human coexistence in wartime,

too bad it’s worn out!),

for one family, fractured and incomplete…

then explain to someone how in those first months we only crossed paths accidentally

for a few minutes just on business, sometimes on the street, not acknowledging each other at first,

startling, as if recalling something hopelessly lost and irretrievable

hugging instead of words to hide streaming tears:

—how are you—how are you (not a word about literature)—hang in there—hang in there

silent and focused, like the first Christians

who witnessed Christ’s miracles with their own eyes and had no idea

how to fathom it and how to tell others so they’d believe and wouldn’t mock them,

how not to twist or muddle things,

because it’s never clear which are the important details and which can be disregarded

then in each account we omit the parts about ourselves,

like apostles on opposite ends of the world, each preaching our own version of the gospel

because any faith depends on a million eyewitness accounts,

on countless private stories from that point in reality,

where no one knows anything yet, or understands

what that man did beside the dead Lazarus, and how he did it,

how everyone saw, but not everyone immediately believed…

especially if this faith in victory comes from a point not yet visible

this is how they’ll describe it in the early ’30s in the relevant chapters on Ukrainian literature

the main thing is not to forget that none of this was about literature

***

by Halyna Kruk

and Jesus ascended at the Mount of Olives

in the city of Bucha, in the city of Irpin,

in the town of Hostomel, in the village of Motyzhyn

in the town of Borodianka

in the city of Chernihiv, in the city of Kharkiv,

in the long-suffering city of Mariupol

and prayed to the Father–

let this cup stop with me,

crucified on a bodily cross

on an unidentified mortal’s body

2022 the year of our Lord

in a soulless world

heaven and earth walk on by

Translated, from the Ukrainian, by Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk

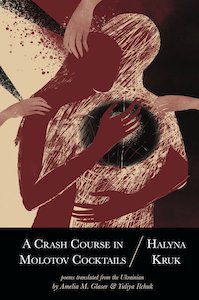

From A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails, forthcoming with Arrowsmith Press

___________________________________

Halyna Kruk’s poems are from A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails, from Arrowsmith Press.