Walter Benjamin sits on a bench scratching his elbow and staring at the sea. He does not stare emptily: images and memories of other seas he has stared at in his fifty-five years on this earth (as a child, the Baltic; as an adult, the Mediterranean) pile on top of each other as he notes how similar and how different they were to the one he now stares at. He is disappointed in himself when after observing qualities of blueness, stillness, and size, he can come up with nothing better than noting that this one is, after all, more pacific.

Walter Benjamin stares at the sea and wishes he had something better to do. Sitting still and staring is something he does often, and is good at, a rare moment of time freed from capital, but he cannot deny that it is, quite simply, boring. Time has never been his friend, but never before has it felt quite such an enemy. He is on the edge of comparing the sea to time but blocks the thought before it turns banal. He thinks he should set out on another book, a long one, but even though he stares peacefully at the Pacific Ocean, he cannot settle for the time needed to concentrate on even the idea of a book and thinks he should instead try to finish the many things he has started. The big book about Paris, for one, but Paris is so distant now. A book about Los Angeles, perhaps, where he currently, unexpectedly, finds himself, staring at the sea, fascinated and bored in equal measure.

A large car pulls up alongside the bench next to him. A man get outs, takes a small black suitcase from the passenger seat, puts the case on the bench, then sits down next to it. Walter Benjamin likes to observe but does not like to engage so does not attempt to strike up a conversation with the man who, in any case, is, like him, staring out at the sea, though in a noticeably more agitated fashion. After a few minutes the man gets up again, returns to his car and drives off, leaving the suitcase on the bench.

Walter Benjamin briefly considers taking the suitcase, as if to replace the ones he has lost, but swiftly dismisses the idea. He no longer wishes to be involved in other people’s lives. He stares at the sea and wonders if anyone thinks of him anymore. If they did, he thinks, they would imagine him exactly as he is: sitting on a bench, unmoving, staring at the sea. He doesn’t talk to many of the old lot anymore. Max, Teddy, Bert. He never really had that much time for them, really, nor they for him. They’re trying to make a go of it out here, but Walter thinks he has come as far as he can and can go no further. He stares at the sea. Everyone, said someone, has one big idea or lots of small ones. He stares at the sea and thinks that he had lots of big ideas.

Another car pulls up, and a woman gets out and sits on the bench next to the suitcase. She is wearing sunglasses and has a scarf pulled around her head to protect her hair from the insistent breeze. She looks out at the sea, then looks over to Walter, but Walter does not meet her gaze. She picks up the suitcase, gets back in her car, and drives off. He thinks again about the suitcases he has lost, and who may have claimed them.

He stares at the sea and cannot stop himself from thinking of what brought him here and remembering the journey variously, perilously. After the scramble over the mountains and the switch in the grubby hotel, he could have taken another long walk to Barcelona and from there boarded a ship bound for safety, or he may have taken a train to Madrid and from there one to Lisbon and stood on a hopeful quay, or a train farther south to Algeciras, then a boat to Tangier, from where he would have travelled to Casablanca and waited, or maybe he never took that route at all, and had got out earlier with an exit visa from France and an entry one to the US, but however he did or didn’t get here, slipping away into crowds with documents and papers and passports forged or real, he is here now, sitting on a bench, quite alone, staring at the sea.

Walter Benjamin decides to make use of his boredom and go to the cinema. He goes to the cinema often, and alone, and he loves it. The Picfair, the Movie Parade, the Hollywood, the Vista, the Million Dollar, El Capitan, the Egyptian. The cinema is, as Gorky said, the kingdom of the shadows and the best place to vanish for a while.

The walk is long, and no one walks in this city but he will not learn how to drive. He has no ability, no interest, and is far too old. There is no bus service he can discern. As he walks, cars occasionally slow and either regard him warily or offer a lift. The latter he waves away. He wants no charity from strangers.

He loves the cinema but often hates the films. The only ones he likes are the crime films, though not the ones with gangsters but the ones about lonely and desperate men or women trying to find a foothold in life, taking risks, disappearing then remaking themselves. He should write something, he tells himself, about these films, though he knows he never will. He walks into the movie theatre even though the show has already begun. He enjoys watching films this way, walking in halfway through and not leaving at the end of the screening but waiting for the programme to begin again. In this kingdom of shadows everything has already passed, and not yet come.

A woman comes in and sits near him. She puts a bag on the seat next to her (a suitcase, notes Walter, thinking about how all suitcases look the same but never are), then fidgets and looks over her shoulder as if waiting for someone to arrive. No one arrives. The woman opens the case, takes some things from it (Walter cannot see what they are), then leaves in the direction of the restroom. A few minutes later she returns, a different woman. This woman is dark-haired, whereas before she was blonde. This woman is heavily made up and wears a scarf around her neck. She waits a few more minutes, then leaves, not taking the suitcase with her.

Walter Benjamin stares at the screen and thinks he should be a detective. Every corner of this city, he thinks, is the scene of a crime.

Walter Benjamin sometimes wonders what he is doing here and other times if he is here at all. As he leaves the movie theatre and begins the long walk back to his bench overlooking the sea he passes the precinct police station and thinks he should go in and report himself missing. I am Walter Benjamin, he will say, and I am a missing person. There will be the usual confusion, and the desk sergeant will register him as Benjamin Walter. He will then leave and remake himself as Ben Walter, a private detective, or a photographer, or a newspaper drudge, a hack writer of pulp novels or screenplays. Ben Walter could smoke lots of grass and listen to jazz. He could wear a hat.

__________________________________

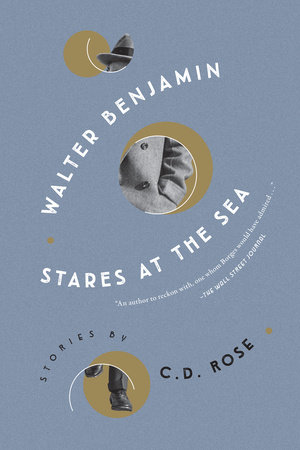

From Walter Benjamin Stares at the Sea by C.D. Rose. Used with permission by Melville House Publishing, Copyright © 2024 by C.D. Rose.