Walking with the Ghosts of Black

Los Angeles

Ismail Muhammad: "You can’t disentangle blackness and California."

My maternal grandmother Olivia Duffy never intended to live in Los Angeles; her arrival in the city was the result of a merciful instance of deus ex machina. A high school graduate without the means to attend college in her home state of Louisiana, but who had heard stories of black communities flourishing in Oakland, California, she joined a childhood friend in stuffing her belongings into the back of a car.

They drove west from Oakdale in the summer of 1945, but their timing was off. The journey ended up being belated, and by the time they crossed into California, America had dropped two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The tragedies on the other side of the Pacific signaled the end of both the war and the wartime economic boom that had drawn so many African American migrants to California. They flocked to Oakland’s shipyards and transformed themselves into crucial elements of the American war effort; in the process, these migrants transformed Oakland into a stronghold of African American political activism and culture.

All that turned out to be of little consequence for my grandmother. Olivia and her friend had been taking their time nearly 400 miles south of Oakland, driving down Abbot Kinney Boulevard in Venice Beach. Who knows why they chose to dawdle—maybe they took news of the war’s end as the end of their dream in Oakland, maybe they allowed themselves to delight in the low-slung bohemian charm and creeping decrepitude of that bizarre neighborhood, a rundown former tourist resort modeled after the Venetian canals, so unlike anything they’d known in the woods of rural Louisiana—but suddenly they felt hesitant about continuing on to Oakland. Luckily, the car made the decision for them; before long its engine began to wheeze. They became Angelenos by happenstance.

Olivia settled into a Venice boarding house while working as a caretaker. Eventually she’d saved up enough money to purchase a bungalow on Broadway Street, at the center of Oakwood, Venice Beach’s black enclave. Her mother got tired of Jim Crow and followed her daughter to Los Angeles, taking up residence in the Broadway bungalow. It was there that Olivia made her life, not Oakland: there that she built a business offering caretaking services to local elderly people; there that she gave birth to five daughters; there that she married men when she was in love with them, and there that she divorced when she tired of them. It was in Los Angeles that my grandmother, seeking a freedom that she couldn’t imagine in Jim Crow Louisiana, decided to make a home.

You can’t disentangle blackness and California.

Olivia eventually moved her family out of the Westside, to the South Los Angeles community of Vermont Square. For the majority of its existence in California, my family has resided in South Central. Venice still possesses a nostalgic appeal for my family, though, as the neighborhood where our history in California begins. It’s part of our origin story, which I proudly recite to anyone who will listen. I got the habit from my mother, who would tell me stories of what it was like to grow up on the Westside in the 50s and 60s, when Venice was dubbed the Slum by the Sea and the neighborhood attracted a motley assortment of black and Latino migrants, European immigrants, and poor artists.

She’d talk about worshipping at Friendship Baptist Church, down the block from Olivia’s bungalow, back when the church could draw more than a dozen worshippers; about barbecues at the park on Oakwood Avenue, and learning to play domino with Kineas at the park’s long tables; about rollerblading over to the beach and attending school at Westminster Elementary on Abbot Kinney, where most of her classmates were black. My mom would tell these stories like a woman possessed. When she told then, her voice was seized by the memory of a lifestyle threatening to waft away on an ocean breeze.

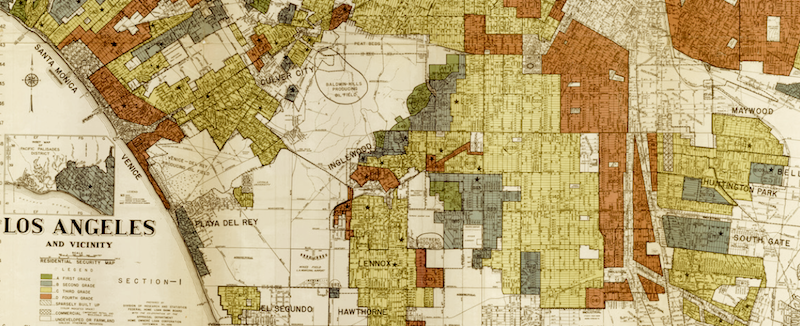

Her memory elided a sobering fact about the social history that created Oakwood. Like many black communities in Los Angeles, Oakwood was in part a product of housing covenants that prohibited black people from living in certain parts of the city. In Venice’s heyday as a resort destination, blacks were forbidden from owning property near the neighborhood’s beaches and canals. Fearing violence if they dared to transgress the city’s de facto segregation, African American migrants in Venice settled slightly inland, creating a community similar to the black ghetto that had coalesced around Central Avenue, just south of downtown Los Angeles. They named their community Oakwood, but white residents had another name for the district: “Ghost Town,” a presence that was, for all intents and purposes, an absence.

*

You can’t disentangle blackness and California. California’s history in the public imagination is tangled up with blackness’ history as the fundamental marker of racial difference in the modern world, the sign by which we know what is irretrievably alien, irrevocably other. In my mind, the idea of a “Black California” is redundant: as a concept, California began as a speculative fiction with a disavowed blackness lodged at its center. In 1510, the Spanish romance writer Garci Ordóñez de Montalvo published Las Sergas de Esplandián, a sequel to his popular Amadis de Gaula. In Las Sergas, the Christian hero Esplandián defends Constantinople from an army of Muslim invaders led by the pagan Queen Calafia and her army of Amazonian warriors.

Montalvo’s Calafia was not a delicate European beauty, but a regal African warrior. “She was not short, nor white, nor had golden hair,” he wrote. “She was huge and black, same as the ace of clubs.” She didn’t hail from a land any European had set eyes upon; her kingdom was a matriarchal society of fantastic wealth, “an island on the right hand of the Indies . . . very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise.” Her blackness marks her not only as an irreconcilable foe of white Christian civilization who must be defeated and converted, but also an available, willing target of plunder.

If laws didn’t prevent black migrants from overstepping their bounds, the threat of violence sufficed.

Accordingly, Esplandián defeats Calafia, who accepts Christianity and marries one of Esplandián’s generals before returning to her kingdom and claiming it for Christianity. The Spanish had developed a host of stories similar to the Calafia myth—the seven cities of Cíbola, the lands of the gilded king El Dorado, who coated himself in gold, the kingdom of Gran Quivira—that spurred explorers into the vast unknown interiors of the American continents. But the dream of Montalvo’s “Terrestrial Paradise” was so powerful that it eventually came true.

Envisioning a land awash in gold and ripe for conquering, Hernán Cortés led an invasion of Mexico in 1518, where he instigated the fall of the Aztec Empire before commissioning an expedition to sail west from Mexico in 1533. The Spanish explorers quickly made landfall on what they thought to be an island, but was actually the southern peninsula of a much larger landmass. The Spanish, ever eager to see their visions of paradise materialize, called their island California, after Montalvo’s conquered queen. Cortés himself arrived in Baja California in 1535, and spent years attempting to found a colony on the peninsula’s inhospitable landscape, certain that if he succeeded, he could continue north, penetrating the land in search of untold riches.

*

In the early 20th century, African Americans considered Los Angeles a refuge, a place where they might achieve prosperity unlike any they could know in their Southern homes. Legalized discrimination was less codified than in the Jim Crow South, affording black migrants like my grandmother a level of economic opportunity unheard of in the Southern cities from which they hailed. Settling around Central Avenue in neighborhoods like Watts, blacks began to build a community whose prosperity was, if limited, still unusual among black Americans.

After visiting Los Angeles in 1913, the scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois enthused about the city in terms that evoked Montalvo’s Terrestrial Paradise. “One never forgets Los Angeles and Pasadena,” he wrote in a brief account of a visit to Southern California for the August 1913 issue of Crisis. “One never forgets Los Angeles,” he rhapsodized. “[The] sensuous beauty of roses and orange blossoms, the air and the sunlight and the hospitality of all its races lingers long.” Du Bois seemed most enamored of the material comforts some black migrants were able to achieve in Los Angeles. He punctuated his article with photographs of handsome homes, successful black-owned businesses, and respectable middle class families. On the issue’s front cover a nattily dressed black Angeleno reclines on a craftsman home’s well-manicured lawn, enjoying a palm tree’s shade.

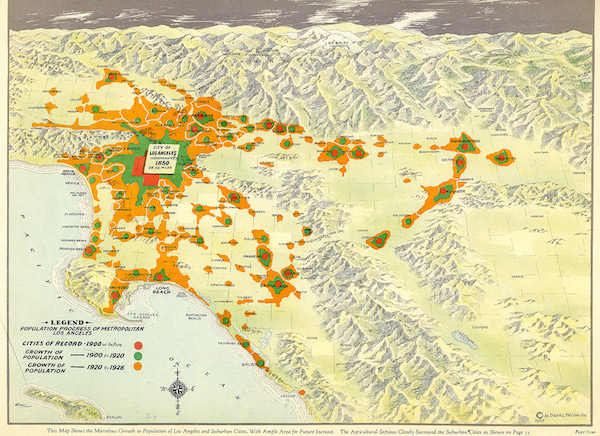

What Du Bois would not or could not say, lest the California myth dissolve: this prosperity was contingent, wholly at the mercy of the city’s white power brokers. As migrants of all races made their way to Los Angeles, the city’s population grew at a rapid rate. Many of these migrants were white Midwesterners. By 1926 nearly 90 percent of all Angelenos were white, and they used the law to ensure their power. Even as Du Bois sang black Los Angeles’ praises in 1913, the California legislature passed the Alien Land Act, which prohibited the sale of land to Japanese immigrants. Within this power structure, blacks could prosper—but only if that prosperity didn’t threaten that of white Californians.

Once the war was over, though, white Los Angeles saw the city’s black residents as a problem to be curbed.

Southern black migrants tested this delicate balance over the course of the 1920s and 1930s, flocking to Southern California in numbers that swelled the ranks of the South Central community. In 1920, African Americans were a small minority in Los Angeles, around 15,000; by 1940, they numbered over 100,000 people. The city’s white power structure responded by intensifying racial discrimination. Racially restrictive housing covenants, restrictions around where and when African Americans could use public swimming pools, and school segregation became the norm.

If laws didn’t prevent black migrants from overstepping their bounds, the threat of violence sufficed: the year after my grandmother arrived in the city, O’Day Short and his family integrated a white neighborhood in the de facto segregated city of Fontana. White neighbors greeted them with a cascade of death threats culminating in a bombing that destroyed the family’s home. Short, his wife Helen, and their two children Barry and Carol Ann were murdered.

In 1952, William Bailey, a science teacher at Carver Junior High School, moved into a house in the West Adams district with his wife and son. West Adams, a white neighborhood on the western edge of the South Central ghetto, had been the site of violence a year earlier when a Japanese American doctor’s home was bombed. Bailey’s home suffered the same fate; witnesses reported feeling the explosion’s force up to ten miles away from the blast.

Los Angeles’ transformation from a sleepy agricultural town into an industrial city was in part the result of African American migration to Southern California. Once the war was over, though, white Los Angeles saw the city’s black residents as a problem to be curbed. The prosperous little paradise that Du Bois encountered during his 1913 visit began to tremble under the weight of white fear.

*

People tend to speak of South Central Los Angeles as a homogenous neighborhood, an undifferentiated community of African Americans wracked by poverty, gang violence, drug use, and general social disorder. In actuality, South Central is not a neighborhood at all, but a massive swath of the city settled by black migrants in the 20th century. It’s a radically horizontal post-industrial landscape where buildings rarely exceed two or three stories and pedestrians find little shelter from the sun. Down Slauson, decommissioned train tracks that once carried freight from the Port to the inner city call to mind the region’s formerly robust economy.

Surreal sights crowd the streets: men dressed as the Egyptian Pharaohs to whom they believe themselves related; the inordinate number of storefront churches that line the streets of any community wealthier in hope than capital; music video shoots depicting absurd extravagance while obscene poverty lingers just outside the frame; Nation of Islam adherents dressed in gray suits while hawking newspapers in hundred degree heat. Looking up from the basin that South Central occupies, one’s eyes make out the opulence of hillside communities to the north and south, the beauty of the San Gabriel Mountains rising to their snowy peaks. It is an impossible land, a land of preposterous contrasts.

South Central became a catchall term for anywhere black bodies were found.

The region’s boundaries expand and contract depending on who you ask: for some, it might include only neighborhoods within Los Angeles proper, bound by the 10 freeway to the north, the 105 to the south, Alameda Street to the east, and La Brea to the west, an area that spans from tony mansions of West Adams in the northwest to poverty stricken blocks of Watts in the southeast. Practically, South Central might also include cities that are technically separate from Los Angeles, but feel culturally contiguous; its difficult for me to imagine a definition of South Central that doesn’t include the cities of Inglewood and Compton, where many of my aunts, uncles, and cousins lived before leaving the city.

The name “South Central” is itself rather meaningless: it refers to the historically black district just south of downtown Los Angeles, anchored by Central Avenue. As new migrants arrived, affluent black Angelenos pushed their way westward, gradually expanding “South Central” until it included areas far from Central Avenue. South Central became a catchall term for anywhere black bodies were found. Anywhere that white people did not want to be.

South Central is a rhetorical ghost town. It’s a synonym not only for black Los Angeles, but the inner city blight that overtook black communities in the late 20th century as the industrial economy ground to a halt and the crack cocaine economy rose to take its place. In common parlance, “South Central” is a synonym for “black,” for undesirability, for occluded possibility, for the end of the dream of prosperity. Today, South Central functions as a ghost town, an absence rather than a presence.

Beneath this sign lies the reality. South Central is an imbricated set of communities whose commonality begins and ends with their blackness—or, at this point, the memory of the black people who once called those neighborhoods home, and the culture they gave rise to. It’s a space of stunning social and economic heterogeneity, where the worst effects of the Reagan years coincide with the material ease that Du Bois envisioned.

*

I grew up in Windsor Hills, an unincorporated community in southwest Los Angeles County, sandwiched between Inglewood to the south, Culver City to the West, and the Crenshaw district to the north. Perched above South Central’s post-industrial flatlands, Windsor Hills was something of an anomaly in the 90s and 2000s: a cluster of middle class black prosperity nestled among communities that outsiders thought of as cesspools of poverty and gang violence.

The locals call it Black Beverly Hills, and even as a child, I perceived the neighborhood’s unlikeliness. A certain unreality draped itself over our green lawns and two-car garages. If Windsor Hills was all you knew about South Central, you might think the last 30 years of American history had never happened. The crack epidemic, the War on Drugs, the explosion of the prison industrial complex—none of that seemed to have touched Windsor Hills. That was the point of Windsor Hills. It provided us with a reason for optimism, an exception to the despair that reigned just to the south and north of us.

For most of my youth, Windsor Hills was all I knew about South Central. My life was in pointed opposition to those of my aunts and cousins who lived just down the hill in the Crenshaw district. It was a youth spent with both my parents in our nicely appointed four-bedroom home, where gaudy rococo furniture carved out of polished wood held aloft busts of imagined African royalty, and portraits of African American political heroes—Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey—lined the walls.

I had my own bedroom, a bedroom bigger than some people’s kitchens, with a window that looked west out over Culver City so that I woke up to the sight of palm trees swaying in the morning wind. My mother shepherded my brother Isaiah and I to school in her roomy sedan, then whisked us home in the afternoons so that we would complete our homework under her stern supervision, without the distractions that my older cousins fell prone to on South Central’s wide tree-lined boulevards. I would never fall prey to gun violence, or a police officer with an axe to grind on a black youth, or drug dealer attempting to make a bit of money. Instead, every night I ate a homemade dinner—some variation on a soul food recipe that my mom inherited from Olivia—then finished the night reading next to my younger brother in our spacious living room before bed.

The conditional nature of our exceptionality never felt truer than when a white family arrived to claim a foreclosed property.

What is there to say about my mom? Her life encompasses South Central’s extremes. She grew up in poverty in Vermont Square and Crenshaw after the Watts Riots, then opened up a string of small businesses that eventually earned her enough money to achieve that oldest of Los Angeles dreams: buying property. By the age of 35, she had ascended from the city’s flatlands to Windsor Hills. Her trajectory meant that she knew how easily a black life in Los Angeles could veer into tragedy, how simple it was to be introduced to heroin or crack cocaine at a party, how simply one crossed the threshold into the walking death of addiction, how rare it was for an addict to retrace their steps back over that same threshold.

Fear imprinted itself on her mind and despite her best efforts, she would reflexively transmit that fear to us. When I refused to do my homework, she’d chastise me with the examples of the addicts who ambled up and down Florence or Slauson Avenue. Once, when I was ten, she caught me playing a video game instead of doing my math homework—a sure sign I was headed to prison, or worse. The next morning she woke my brother and I up early and took us cruising down Slauson, pointing out the homeless people who ambled alongside the avenue’s defunct railroad tracks. “Do you want to be like them?” she asked me. “Keep fucking around and that’s what will happen.”

I never forgot the image of one woman, who dug around in a dumpster outside a grimy fast-food restaurant. With one hand she tossed the useless trash into the street and separated the potentially valuable recyclables into a grocery cart that she held steady with the other hand. My mom came to a stop at a red light, and suddenly the woman and I were parallel to one another. Sensing an audience, she glanced up; we made eye contact through the window, and her hazy brown eyes transmitted something to me: a mix of fear, shame, and anger. I remember shuddering in receipt. In South Central, we were always wallowing in this mélange, breathing it in, drinking it in with our mothers’ milk.

*

Windsor Hills hadn’t always been a black district. Until the Supreme Court ruled in the 1948 case Shelley v. Kraemer that racially restrictive housing covenants were illegal, Windsor Hills was an exclusively white community in the mold of Brentwood. Its story is consistent with the history of housing in 20th-century America—as blacks fanned out across South Los Angeles, they triggered a decades-long white exodus from the county’s southern reaches. The truth is that Windsor Hills exists because white people did not want it. When I grew up in the Hills, it was easy to forget this, to pretend that it was an ahistorical black utopia, some kind of exception to the tragedies that unfolded beneath it. It was our dream of plenty.

That changed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when foreclosure signs began to appear in the windows of my neighbors’ houses and weeds began to choke their immaculate front lawns. Suddenly our community felt contingent. Black Beverly Hills started to fray at the edges. The conditional nature of our exceptionality never felt truer than when a white family arrived to claim a foreclosed property.

Picture me walking down the street early one fall evening in 2011, that utopian fiction fully naturalized in my head. I’ve just gotten off the 212 bus from downtown Los Angeles after spending a day at the Central Library doing research for my graduate school applications. I’ve recently graduated from Columbia University so I’m feeling like nothing can touch me—I’ve managed to avoid the fate of the woman on Slauson.

Then I see a trio approaching me from up the street. They are newcomers to Windsor Hills. Gossip about them has spread across the neighborhood in short order: a young white couple and their five-year-old daughter, recently arrived from Studio City. They are hand in hand in hand, arms swinging arrhythmically—they seem happy to have found a house in my prosperous neighborhood. They’re sporting that mask of joviality common to rich white people, the kind I associate with Republican presidential candidates and people who aren’t against affordable housing per se, just the potential damage it might do to their property values.

Eventually they are no more than ten feet away and I can tell they’ve spotted me because those masks slide and I can see something shift in them. The mother’s hand tightens around her daughter’s, the father pulls his wife closer to him. I feel something shift in myself; my ears go numb, my face feels hot. Eventually they outright cross the street and I am on that sidewalk alone again, but changed. The whole of Windsor Hills is changed; history has returned, and I feel like a ghost in my own life.

*

The artists of the Los Angeles Rebellion took a particular interest in South Central. They were a cohort of black filmmakers who gathered in and around the graduate film program at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the aftermath of the Watts Riots. Though, like so many black Angelenos before them, most of the LA Rebellion filmmakers did not hail from Los Angeles—Julie Dash came to UCLA from New York, while Charles Burnett arrived from Mississippi—they were drawn to South Central. In its boulevards they perceived a possibility or spiritual charge that others could not.

Many of their films take place in the post-apocalyptic streets that my mom taught me to avoid at all costs, mining their surreal tragedy as the source of a spectral power. Barbara McCullough’s 1979 short film Water Ritual #1: An Urban Rite of Purification opens on a dilapidated shack in the midst of field choked with destroyed houses and desert shrubs. It’s a section of Watts that the city emptied and then bulldozed to create a path for a freeway. A lone figure reclines in a ruined house whose stucco walls have crumbled, revealing the absence within.

Yet she luxuriates, stepping out to sit amidst statues that resemble the orisha of Yoruba faith. As the camera pans across these totems, we find ourselves suspended in a realm of possibility: South Central’s bombed-out landscape becomes the grounds upon which we might summon ancestral spirits, a blank space in which our protagonist summons a new kind of sociality, one that might exceed the devastation wrought upon the landscape. Insofar as McCullough intends Purification to be a participatory film, not just a viewing experience but a ritual into which we might enter and through that entry be changed, the film ushers us into the embrace of this trans-temporal summoning.

Then, suddenly, in the top left hand corner of McCullough’s camera, one can spy a car speeding up the street in the distance. Rather than edit that car out—whether because of the necessities of shooting an independent film on the cheap, or out of specific intent—McCullough has allowed the details of Watts in 1979 to penetrate her purification rite.

This is not a new space: we are still rooted in black Los Angeles, a space characterized as much by loss and absence as by the vibrant creativity of the people who call it home. I love that moment because, when that car cuts through McCullough’s film, dreams of escape, untold riches, and utopian achievements fall to the wayside. She allows black Los Angeles to be what it is, a constant churning wherein absence becomes the condition of a new summoning, and where summoning will always yield an absence of some sort. Black Los Angeles becomes the ghost town in which, like my grandmother did in 1945, we yield to chance’s capacity to create beauty. It is the space in which the city’s capacity for constant reinvention takes its clearest shape.

________________________________________________

The preceding is from the Freeman’s channel at Literary Hub, which features excerpts from the print editions of Freeman’s, along with supplementary writing from contributors past, present and future. The latest issue of Freeman’s, a special edition gathered around the theme of power, featuring work by Margaret Atwood, Elif Shafak, Eula Biss, Aleksandar Hemon and Aminatta Forna, among others, is available now.

Ismail Muhammad

Ismail Muhammad is a writer and critic based in Oakland, California, where he works as the reviews editor at The Believer and a contributing editor at ZYZZYVA. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, Bookforum, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among other venues. He is currently working on a novel.