Walking Through Jose Esteban Muñoz’s New York City

Marcos Gonsalez on the Great Queer Theorist’s Life and Legacy

More than a decade after his death, Jose Esteban Muñoz’s faculty page is still up on NYU’s website. It lists his former office address, 721 Broadway, 6FL, marking an absence that is now someone else’s presence. Office space in downtown Manhattan, where NYU is located, is too expensive to let the fear of a haunting keep space unused. The website also lists his research interests: “Latino studies; queer theory; critical race theory; global mass cultures; performance art; film and video.” The catchwords seem too simple, too reductive, to speak to the nature of his expansive, unsummarizable theorizing. His email in the corner of the page: jose.munoz@nyu.edu. A lure for epistolary desiring. Cold emails beyond the grave.

*

Whenever I walk to the queer bars in the West Village (places I, a happy-hour connoisseur, frequent often), I pass by the building where Muñoz’s office was located. It’s an unimpressive structure, right on Broadway. The purple NYU Tisch flag waves out front. I stare up at the sixth floor, not knowing which exact window would have been his. The window in the photo of him working in his office could be any of these. Each a windowpane a portal to the sliver of an office inside. I search for an outline akin to Muñoz’s in the office photo: a bigger body, slightly hunched over, in a sweater and glasses. I look for the ghost of him in his former office. Hoping for one of the signs from the dead that my Puerto Rican grandmother believed in so passionately—the departed manifesting in a place they had frequented in life, reaching out, communicating, imparting a message. I stand on the bustling sidewalk, staring into the offices above, fantasizing the outline of the theorist at work, a glimpse of him tap-tapping at his desktop computer, concentrated, laser focused on his next book or article, finessing a new concept, developing upon an old idea, toiling away on his next project, which we will never read and never know. My reverie is cut short by practicality: Why would anyone want to haunt, reside in perpetuity, in their former place of employment?

I was thirty years old when I got my own office for the first time. Before then, privacy had been at a minimum; spaces in which to work and think in were difficult to attain. In high school, my bedroom wasn’t large enough to even hold a desk, so I did my homework and reading on my bed or at the kitchen table. As an undergrad I was fortunate enough to have a desk in my series of cramped dorm rooms, but the hubbub of roommates and college life made the space unideal for writing and thinking. Grad school was the first time in my adult life when my housing had a private bedroom where I could work on my own terms. Because grad school centered on independent studying and writing, I could often work from home rather than go to campus. I quickly realized, however, that working, resting, and sleeping all in the same space wasn’t such a good idea. My body could not distinguish between the time meant for work, the time for unwinding, and the time for sleep.

This was the New York City that marks Muñoz’s entire body of work, making possible the artists he came in contact with and the analyses he produced.

It wasn’t until after grad school, when I began receiving a salary from my first tenure-track job, that I was able to afford an apartment with an extra room for an office. I have never thought so clearly as when I’ve been inside my own office. A room solely dedicated to reading, working, and thinking, where no one can disrupt my concentration by shuffling in or out. I’ve filled my office with ceiling-height bookcases, with a filing cabinet storing all kinds of documents (museum tickets, playbills, syllabi, exhibition handouts, unpaid bills, unsent postcards), with art. My office is a room of intellective possibility. The first place I have been able to get fully lost in thought, where thought and inquiry are nurtured, where I can play around with ideas. Maintaining this office—and by maintain, I mean continuing to earn enough in order to afford the space—is the difficult part. Twenty-first-century capitalism has commodified every last inch of space, particularly those in cities, making it impossible for anyone not making six figures, or those who don’t have a multiple-income household, to secure decent living arrangements.

We all deserve to have a space to think in, even those of us who aren’t writers, artists, or academics. A designated room in which to reflect and contemplate, apart from the routines of the kitchen, the sanctum of the bedroom, the noise and activity of the living room. A room to be alone in. An office really isn’t a luxury, and when we think of it as so—when we agree that having multiple rooms is a privilege that only some can afford—that’s when the bosses and the landlords win. The center can no longer hold. Why not fall through like Alice, curious about the rabbit hole’s end, and see what’s on the other side?

*

Muñoz lived in the New York City of the 1990s and 2000s, which was very different from the one I live in now. He lived in a network of artists and critics running about the city, high off cheap rents, cheap taxis, and cheaper living. He saw experimental theater flourish, saw performance artists of varying races and classes doing the most in the clubs. Later, he witnessed the “cleaning up” of Times Square, a process of gentrification set in motion by Mayor Rudy Giuliani, documented in Samuel R. Delany’s 1999 essay collection, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (a text Muñoz wrote about). He was here during 9/11 and its aftermath, as he wrote about in a pedagogy essay. He visited queer clubs in Manhattan and Queens spending time in those spaces so that he could later theorize upon them in his books, noting how one day the clubs were there and the next they were gone. This was the New York City that marks Muñoz’s entire body of work, making possible the artists he came in contact with and the analyses he produced.

Muñoz and I shared the same New York for three years—starting with my arrival in 2010, ending with his death in 2013—but that New York was already so different from the one he’d come to know in the 1990s, when he started his job at NYU. The New York that greeted me as a precocious eighteen-year-old was one of unaffordable rents and high prices. Splurging on a drunken night out and a cab ride home would mean a skipped dinner (or two) to make up for the costs of such opulence. I have watched the city expand its army of cops through the years, to harass children jumping the turnstiles and unhoused folks sleeping on subway platforms. At Rikers, the jail overstuffed with incarcerated humans, conditions have worsened year by year, inmates dying at alarming rates, the carceral state consolidating its power in order to make the wealthy few feel “safe” in the big city. The New York I have lived through is one where artists and critics can no longer afford to build a life as our elders did, those who came before us with no money to their name but still made it, Warhol, Ginsberg, Haring, their names now monetized by the same city officials and the bourgeoisie who are actively erasing the material conditions that gave rise to such innovators in the first place.

Under twenty-first-century capitalism, New York artists and intellectuals cannot create communities organized around experimenting with aesthetics, sexuality, ideas, gender expression, or forms of living. At least, not together in person. Perhaps social media and online forums will host the next great wave of the avant-garde. But I am not too sure about that either because no matter where we are in the world, capitalism still stifles, interjects. Even when you’re behind a computer screen or your phone, your rent is still too high, your credit card and student debt are through the roof, you’re working too much, your attention span is absolutely shot from the stress of it all. Internet prices continue to surge too, further hampering the prospect of your digital avant-garde! Where and when can art and ideas still flourish, under the global conditions we all must endure? There has never been a utopia in New York. No true utopia can blossom on stolen land whose keepers refuse to return it—who refuse, even, to admit that a violence has taken place, refuse to atone materially or structurally for all the enslaved and exploited who were forced to build a society, brick by brick. The New York of the 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s was by no means even close to utopia, especially for folks of color. But there were glimmers of possibility that we can mine for a politics of the utopic. A utopia we have yet to see, that may require revolutionary gusto, a demolition-like impulse that isn’t afraid of a world entirely strange to this one. We may not have Wilde’s map, but we can work to draw it.

_____________________________________________

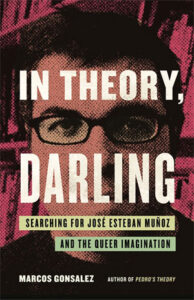

Excerpted from In Theory, Darling: Searching for José Esteban Muñoz and the Queer Imagination by Marcos Gonsalez (Beacon Press, 2025). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Marcos Gonsalez

Marcos Gonsalez is a writer and doctoral candidate in English Language and Literature based in New York City. His memoir about coming of the queer son of an undocumented Mexican immigrant and Puerto Rican mother in white America, Pedro’s Theory, is forthcoming with Melville House. His essays have appeared in Electric Literature, Ploughshares, Inside Higher Education, Ploughshares, Catapult, The New Inquiry, and elsewhere.