Wakanda Forever: How the Black Panther Salute Links the Black Community

William Evans on the Light and Legacy of Chadwick Boseman

We catch it at about the 45-second mark of the second Black Panther trailer. Chadwick Boseman, aka T’Challa, aka the Black Panther, is walking through an Afrofuturistic lab where he greets Shuri, the Wakandan princess played by Letitia Wright.

The greeting follows the two-beat tradition. The dap is always on the upbeat. The initiator. Anyone can get this step. Even the outsiders. Even the colonizers. The open-hand clap. We’re not shaking hands. The fingers angle up toward your recipient’s heart, not at their feet. The downbeat is what tells us what the relationship is. If the fingers lock? We cool. A default setting. Maybe we just met. Maybe we ain’t as cool as we used to be. But we respect each other enough. And this is fine. Maybe it’s a hug. Older heads might pull you in. Now the fists are at the center of our chests. New generation, the hand dap breaks apart before the hug. We clear space. Make room for more. Let nothing hinder this embrace. But Black Panther gave us something new.

Chadwick and Letitia were on some other shit. The dap. Then the arms crossed in front of the body. Fists at your shoulders. The sentient form of “you hold me down and I’ll hold you down.” And we all went, “Oh shit. That’s the move.” It was so simple. It followed our rhythms. It fit into our arsenal of greetings that say, “I see you, and by doing this, I know I’ll be seen.”

The clenched fists are perhaps the most important part of the salute. There is a tension between what appears to be an embrace of one’s self vs. the fists tight against your shoulders. It is resistance. It is a coiled snake. Don’t start none, won’t be none. When you make this salute at someone it means “I got you.” But also, “if we need to, we ride tonight.”

After the bombastic success of Black Panther, the actors were everywhere. And as you would expect of the title character, Chadwick was everywhere. It followed the movie-release blueprint, but obviously, something was different. No movie with a predominantly Black cast and a Black director had ever made this much money before. Which is a long way of saying no Black film had ever brought this many white people to the theater. But it was also different because it didn’t submit to the white gaze.

Chadwick and the team worked on a specific, non-colonized accent. Ruth Carter, the famed costume designer, wove together her own ideas of futuristic design with a reported 100 samples of clothing from across the African continent and its communities. And so, the guilt of enjoying something with largely Black aesthetics that pandered to white folks didn’t exist. So we were all aboard. And we all wanted nothing more than to see the cast talk about their experiences with the film, with each other, and with us after the release.

But now, it is no longer just a gift that Chadwick gave us, but an inheritance.I usually have a hard time with the way we conflate a character and an artist. When someone exclusively refers to a performer by the name of a character they played, I’m usually quick to state there’s a real person under that costume and makeup. But Chadwick loved being Black Panther because we, Black folks, loved him being Black Panther. And nobody did the Wakanda salute more than Chadwick. At the MTV Movie & TV Awards, when he won for best hero and then gave his award to James Shaw, Jr., who had fought off a gunman at a Waffle House. On The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, when he greeted fans expressing their gratitude toward Black Panther and the representation it held. At the Howard commencement ceremony, where he told the graduates about legacy and purpose. At the NBA All-Star Weekend, when he gave Victor Oladipo the Black Panther mask and salute during the dunk contest.

And because the living and breathing internet needs to validate its existence from time to time, the discourse became that Chadwick must be tired of doing the salute. That he looked like he was going through the motions. But then Chadwick again showed us who he was. That he was one of us. On a Breakfast Club interview he said, “I’m not gonna tap-dance. It means something. If you give me the salute, I’m gonna give it back.” Black folks know what tap-dance means. There’s a visceral reaction to invoking the action, when it was predicated by a demand. Chadwick was showing a resistance to commodifying the action. The movie was breaking records, the salute wasn’t a promotional tool anymore. If it ever was. It was a communication. A language we had become fluent in.

In 2018, about a month after the movie had come out, I had to replace the tires on my car. Probably overdue. I walked into the tire place and handed them my keys. I was the only Black person in the waiting room including the staff that I could see. They told me it would take two hours and so I walked the two miles back home. When I returned two and a half hours later, my car wasn’t ready. Actually, they hadn’t even started. The man behind the counter wasn’t very helpful or empathetic. They got busy, he was saying. What I was seeing were cars that weren’t here when I arrived earlier already being done. I was about to argue with this man, pin him down, make him admit he had shoved me to the back of the line. But there was a Black employee, the only one I could see now, who had watched the whole interaction from the mechanics’ bay. He came into the store lobby and told the other guy, “I got him.” They began to argue for a moment before the Black employee shut it down: “He’s been waiting, man, I said I got him. I’ll do his car now.” And then he looked at me. He shook his head. And then he gave me the Wakanda salute. And I smiled, probably the biggest smile that my body could produce, and I gave him the salute back.

After Chadwick Boseman died at the age of 43 from cancer, I found myself tagged in different social media posts. They were mostly of me posing with friends at our Black Panther premiere party. Arms crossed across our chests, fists burrowed into our shoulders. The pictures are from more than two years ago, and today they mean “hold fast.” “Hold tight. We lost another one.” I think of the salute as it originated for me before Black Panther. We’ve all seen salutes by the military on TV, whether they were fictional depictions or at a funeral of a former leader lying in state. But I was never in the military, even when so many of the men in my family were. And I still never saw a salute in person. A lot of uniforms but no salutes. And I wouldn’t, by function. The salute wasn’t intended for me. It was a brotherhood in which I was not a member.

The Wakanda salute is a bitter pill in this way. A simple gesture linking so many of us. An evolution of the nod. The dap from across the room when the distance makes knowing glances too ambivalent. I cross my chest like a sarcophagus in a crowded room and you know what I mean. Any of the dozens of things I may mean. But now, it is no longer just a gift that Chadwick gave us, but an inheritance. Black folks inherit so much, even if it ain’t wealth, so much is left for us. And what could be worse than wasting what your ancestors left for you?

__________________________________

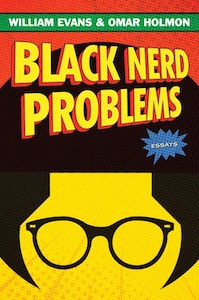

Excerpted from Black Nerd Problems by William Evans and Omar Holmon. Copyright © 2021 by William Henry Evans III and Omar-Abraham Holmon. Excerpted with permission by Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.