W.E.B. Du Bois in Paris: The Exhibition That Shattered Myths About Black America

On the Aesthetics of Research

At the turn of the 19th century, in the Americas, in Asia, and across Europe, the readily summoned image of the Black in the United States was that of an enslaved person, a brown-skinned man or a woman of African descent who worked as a sharecropping field hand on a Southern farm or in a subservient role in a white household or business. Born in a free Black community in Massachusetts, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868–1963)—an African American sociologist, historian, journalist, and anti-racist activist—sought to challenge this image.

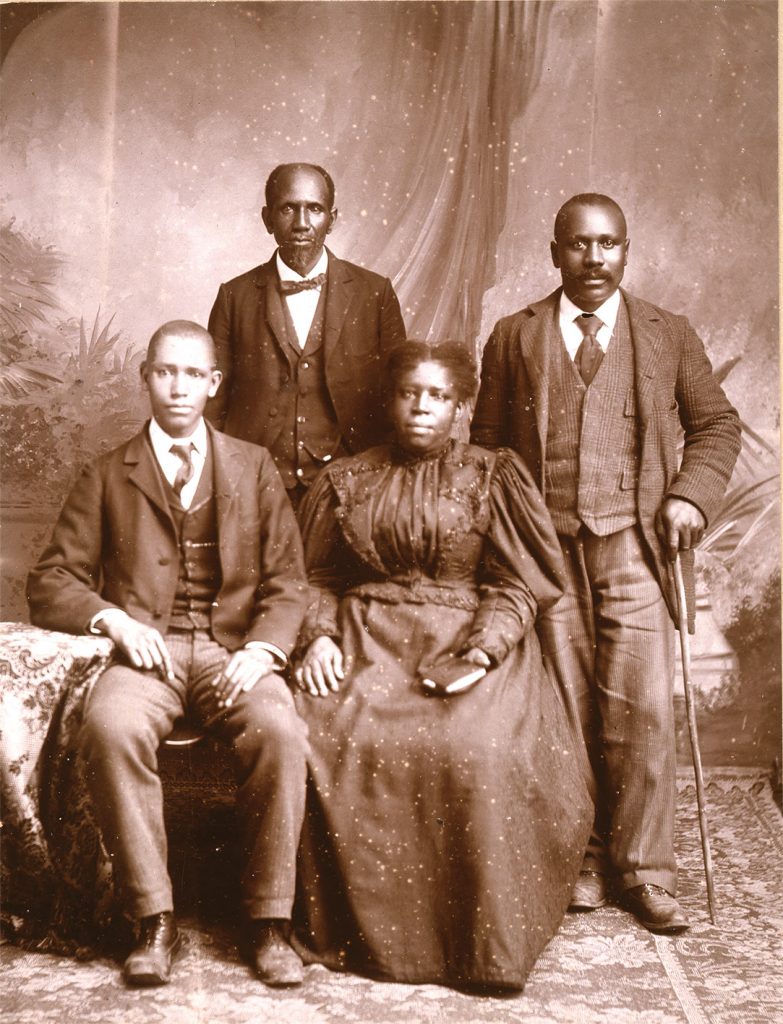

For the 1900 Exposition Universelle (the Paris International Exhibit), he organized a display of hundreds of images: colorful infographics charting African American advancement and monochromatic photographs that presented Black lives, in labor, worship, and leisure, at school, at work, and at home.

Du Bois had been commissioned by his friend Thomas J. Calloway (1866–1930), an African American attorney, journalist, and official for the Exposition’s American Pavilion. His charge was to offer factual information about African Americans, circa 1900, barely three decades after the Emancipation Proclamation that ended the enslavement of Black people in the United States. Calloway’s team also included the famed African American educator and orator Booker T. Washington (1856–1915), African American Library of Congress librarian Daniel Murray (1852–1925), and faculty and students from historically Black colleges and universities.

Over four months, they planned, designed, and procured supporting material, including hundreds of books and pamphlets authored by Blacks; they transcribed U.S. laws restricting African Americans’ civil liberties, statistical research about African Americans, and unique objects related to African Americans’ progress. On display in Paris from April to November, the Exhibition of American Negroes (Exposition des Nègres d’Amérique) was a triumph, garnering several medals for its multimedia display of historical African American achievements and contemporaneous African American ambitions, all undeterred by discriminatory laws, the Ku Klux Klan’s racist terror campaign, and other forms of state-sanctioned oppression. The exhibition subsequently toured to the U.S. cities of Buffalo, New York, and Charleston, South Carolina.

Published visual representation of Black people who lived in colonial America (and later, the United States), can be traced back at least as far as the 18th century. An engraving of the poet Phillis Wheatley (1753–84) is believed to be based on a portrait, whereabouts unknown, by the painter Scipio Moorhead (active 1773), who, like his sitter, had been captured in Africa and sold into slavery in Boston. The engraving is the frontispiece to Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, a volume that includes “To S. M. a young African Painter, on seeing his Works,” an ode that is probably dedicated to Moorehead.

The invention of the daguerreotype in 1838 and the subsequent development of photography gave rise to new claims for a privileged access to “reality.” Unlike paintings and drawings, such chemically produced pictures had an indexical relationship with their subject. This association with authority and objectivity meant that photographic technologies were quickly adopted in service of racist propaganda. Swiss-American biologist Louis Agassiz, for example, collaborated with South Carolina photographer Joseph T. Zealy; their daguerreotypes of enslaved South Carolinians in 1850 attempted to argue that Blacks belonged to an inferior race.

Prints and Photographs

Prints and Photographs

Abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth countered such racist pseudoscience by commissioning studio portraits and cartes de visite, which they distributed widely on both sides of the Atlantic. Photos of these celebrities—and those of distinguished groups such as the touring Fisk Jubilee Singers of Nashville, Tennessee, who performed for Queen Victoria in 1873—bore urgent messages about Black American achievement, agency, and subjectivity.

Photographic evidence also documented deadly white supremacy in the U.S.: journalist and educator Ida B. Wells used news images and commercially produced “souvenir” images of American lynch mobs and their Black victims in her campaign to bring international attention to these abhorrent violations of basic human rights. Notably, Wells allied herself with Douglass and other civil rights activists to publish The Reason Why The Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition, a pamphlet of 1893 that protested African American exclusion from the Chicago fair of that year; it also documented Black American self-improvement and condemned lynching, demanding special legislation against it.

Du Bois’ curatorial project for the Paris Exposition advanced this program of displaying research in an aesthetic manner. He assembled into albums black-and-white and sepia-toned photographs of unnamed African Americans; other pictures on view featured sitters identified by names and appositions, depicted activities or occupation. One image, with the caption “David Tobias Howard, an undertaker, his mother, and wife, seated in horse-drawn carriage, with a tree-shaded house in background, Atlanta, Georgia,” tellingly demonstrates the ideals of financial success, nuclear family ties, and domestic order. Dressed in their best and posed with a servant, the Howards illustrate achievement, just as the exhibition’s statistics did.

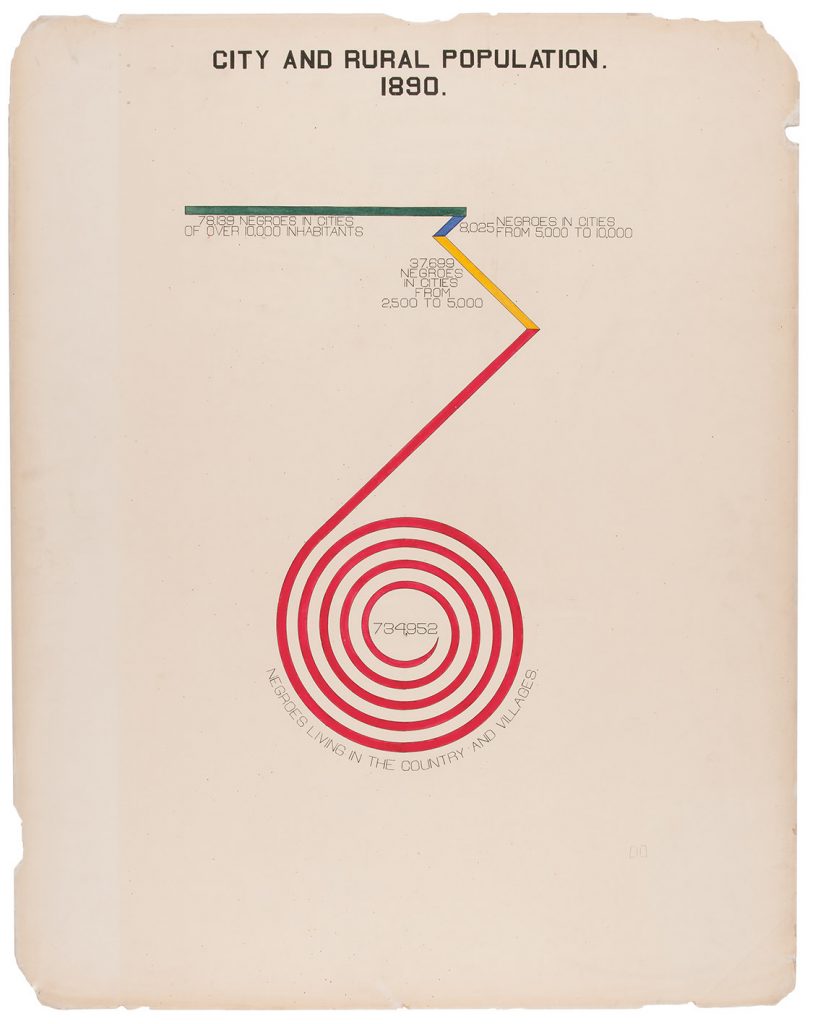

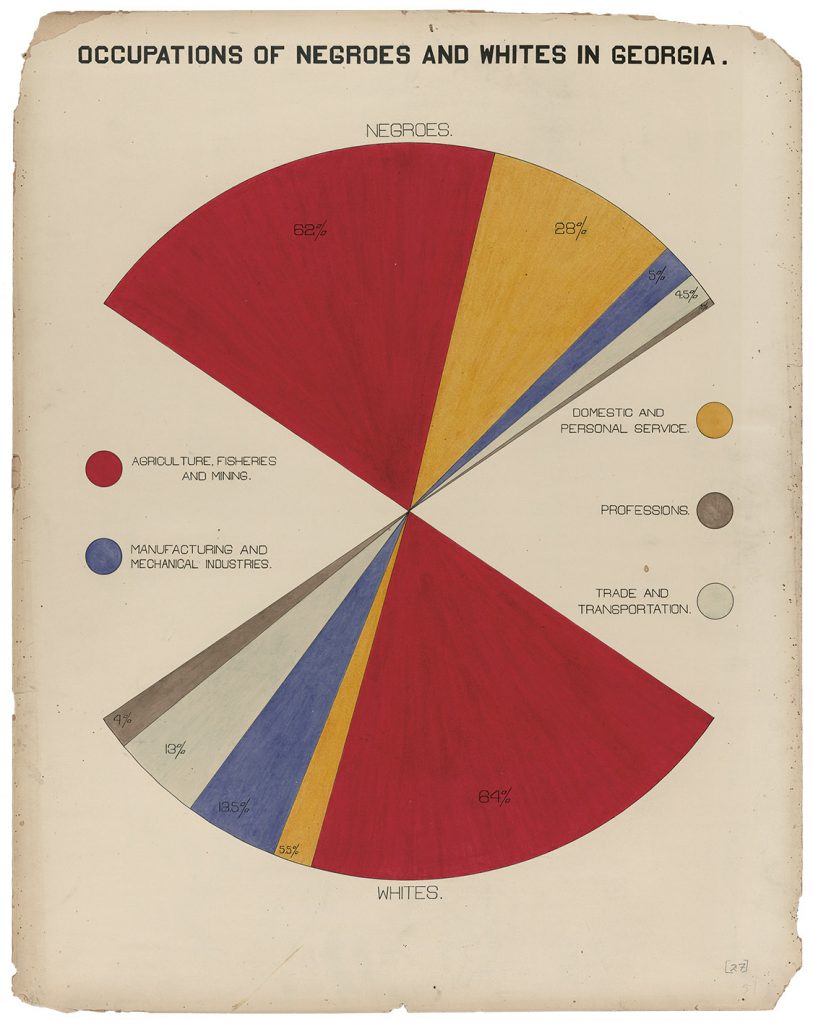

Infographics, realized by Du Bois, sociology students, and graduates of Atlanta University, are grounded in demography, information science, and cartography. The use of basic geometries infuses these sociological documents with authority, indexing the empirical methods of those who gathered facts and statistics, and attesting to their desire for objectivity.

Still, the hand-drawn lines and shapes, and the hand-lettered titles in pie charts, bar graphs, tables, and maps announce that these are unique renderings in graphite, watercolor, and ink (as opposed to cold mechanical prints, reproduced with numbing sameness). While they are not fine art objects, the vibrant palette of these compositions anticipates and resonates with those of Fauvism and Orphic Cubism, short-lived but influential art movements of the early 20th century. As Modernist artists, the makers of these infographics communicated ideas economically, using the universal, highly legible language of design, which was so appealing to popular audiences.

The emergence of Modernist art and design roughly coincided with another phenomenon of modernity: the European colonization of Africa, following the Berlin Conference of 1884–85. The partitioning of the continent, plunder of its natural resources, and exploitation of its human labor provoked resistance and activism across the African Diaspora.

Booker T. Washington, president of Alabama’s Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, admitted Black students from across the world, training them to teach farming and other vocational skills in their communities and home nations. Washington arranged for a program of cotton production in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and German Southwest Africa, and he took a keen interest in supporting Liberia, an independent African nation established as a new homeland for Blacks in the Americas in the 19th century.

Moral suasion, a tactic of anti-slavery forces in Europe and North America in the 18th and 19th centuries, was also brought to critiques of colonialism. George Washington Williams (1849–91), author of The History of the Negro Race in America 1619–1880 (1882), successfully lobbied King Leopold of Belgium to end the inhumane conditions of the Congo’s rubber industry. Alexander Crummell (1819–98), a New Jersey-born Episcopal minister, educator, and Black nationalist, articulated the concept of Pan-Africanism—worldwide Black unity—while earning a degree at Queens’ College, Cambridge. A founder of the American Negro Academy of scholars, authors, and artists in 1897, Crummell influenced a generation of civil and human rights campaigners against racism, colonialism, and discrimination, Du Bois among them.

Just prior to the Paris Exposition, Du Bois traveled to London for the First Pan-African Congress. He was one of 37 delegates who met from July 23rd to July 25th in Westminster Town Hall to discuss a range of subjects: ancient Africa’s contribution to world history; Christianity’s origins on the continent and the effects of missionarism; the legacy of trans-Atlantic slavery; Black self-governance in Ethiopia, Haiti, and Liberia; and self-empowerment strategies. At the conference, Du Bois drafted “To the Nations of the World,” a humanitarian appeal sent to political leaders in the United States and of the European nations to acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent and to end colonial abuses.

In this document, Du Bois re-articulated one of his most famous pronouncements, first offered at a meeting of the American Negro Academy in December 1899: “The problem of the 20th-century is the problem of the color line.” Du Bois’ formidable proposition also appears in one of the infographics for the Exhibition of American Negroes: it is the last bit of text on the introductory plate titled “The Georgia Negro: A Social Study By W. E. Burghardt Du Bois.”

In Du Bois’ sociological text The Souls of Black Folk (1903), this sentence was later expanded to account for race as a designation grounded in comparative descriptions of skin tones and their appearance in the global community: “The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.” For Du Bois, the origins of the problem were found in Europe, the self-assigned center around which “the other,” relegated to the margins, revolved.

What then, could Calloway and his team hope to achieve by mounting the Exhibition of American Negroes in 1900? With dignified studio portraits, genre scenes of workers and students, and an impressive collection of printed matter, they pushed back against ignorance and fought to overturn indefensible and persistent stereotypes about Black Americans. Lively data graphics favorably compared Black American demographics with Germans (fewer of whom were married), the French (less youthful), and Serbians, Romanians, and Russians (lower literacy rates).

Twenty-seven statistical charts offered information in English and French, ensuring that literate citizens of the host country could comprehend the data. The organizers’ efforts indicate their full awareness that they needed to make the most of this rare opportunity to script and visualize narratives of Black accomplishment. Surrounded by exhibits communicating the superiority of European nations and degrading the colonies of Africa and Asia as primitive societies, the producers of the Exhibition of American Negroes identified the Exposition Universelle as a competitive arena in which to garner attention and change minds and hearts about Black humanity.

In 1926, decades after his triumph in Paris, Du Bois published “Criteria of Negro Art” in Crisis: A Journal of the Darker Races, which he had founded in 1910. Du Bois announced to his predominantly Black readership (and, before that, to the Black audience for whom he delivered this text as a speech, during a meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) that all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda. But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.

Although penned in response to literature written by younger African American artists and thinkers during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, it is useful to consider Du Bois’ declaration in the context of the groundbreaking Exhibition of American Negroes. This enterprise responded to propaganda, which is defined as biased and misleading information and the dissemination of it. Confronting historical and contemporary fear and hatred of Black people in Europe and in North America, the organizers of the Exhibition knew that art is a vehicle for ideas, both lofty and ignoble.

They recognized the power of design and display to shape viewers’ experience and create meaning. The above excerpt from “Criteria of Negro Art” is generally read as Du Bois’ attack on the notion of “art for art’s sake.” Yet what also comes across in this passage is Du Bois’ commitment to facilitating “Black joy,” a phrase currently used to describe African Americans’ pursuit and documentation of self-affirming activities. Looking back to the Exhibition of American Negroes, we might view it in a similar light today: namely, as a space of Afrophilia.

__________________________________

From Black Lives 1900: W.E.B. Du Bois at the Paris Exposition. Used with the permission of the publisher, The Redstone Press. Copyright © 2019 by The Redstone Press.

Jacqueline Francis and Stephen G. Hall

Jacqueline Francis, Ph.D., is the author of Making Race: Modernism and “Racial Art” in America (2012) and co-editor of Romare Bearden: American Modernist (2011). With Mary Ann Calo, Francis is working on a new book about African-American artists’ participation in federally funded art programs of the 1930s and their impact on the emergent, US art market of the 1940s. She has published articles on contemporary artists Olivia Mole, Joan Jonas, Andrea Fraser, Mickalene Thomas, and Kerry James Marshall) and (with Tina Takemoto) David Hammons, and on the hot topic of Fair Use. During the 2016-17 academic year, Francis was the Robert A. Corrigan Professor in Social Justice in the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University. In the spring of 2017, she delivered the Richard D. Cohen Lectures at Harvard University. This fall she is the Paul Mellon Guest Scholar at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. She is Associate Professor and Chair of the Graduate Program In Visual and Critical Studies at California College of the Arts (San Francisco Campus).

Stephen G. Hall is a historian specializing in 19th- and 20th-century African American and American intellectual, social, and cultural history and the African Diaspora. As a 2017–18 fellow at the National Humanities Center in Research Triangle, North Carolina, he worked on his second book manuscript, titled Global Visions: African American Historians Engage the World, 1885–1960, which explores the scholarly production of black historians on the African Diaspora. He is the author of A Faithful Account of the Race: African American Historical Writing in Nineteenth-Century America (University of North Carolina Press, 2009).