Vulnerability Never Ends: Madeleine Watts on Coming-of-Age Amidst Climate Catastrophe

Madelaine Lucas in Conversation With the Author of The Inland Sea

Madeleine Watts and I were both raised in Sydney’s inner-west and attended high school in the same suburb, but we didn’t cross paths until one afternoon during our second year of graduate school in New York, making tea in the writing program office at Columbia University. By then, we’d heard rumor of each other—with our first names and origins in common, we had often been confused for one another. These initial coincidences soon gave way to a deeper kinship, and since that first encounter, Watts has become one of my favorite people to talk to about the trials and rare pleasures of the writing process.

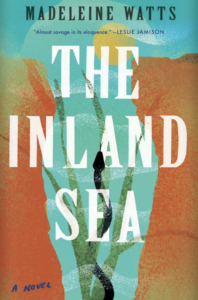

I was fortunate to read her debut novel, The Inland Sea, in its early, nascent form. I returned it to it after its publication in the US this winter, during a particularly bleak and lonely stretch of the pandemic in New York. At a time when I was feeling the distance between where I am from and where I live now more keenly than ever before, reading The Inland Sea felt something like a homecoming: there was Sydney, the city I grew up in, in all its seedy, gothic glory. Not the sunny, beachside paradise that exists in the popular imagination, but an urban inner-city landscape of crumbling terrace houses, brothels and kebab shops that seems, on certain too-hot summer evenings, to pulse with menace.

The Inland Sea follows a young unnamed woman as she drifts through a lost year after finishing university, sleeping with strangers, working at a call center as an emergency dispatch operator and rekindling a slow-burning but destructive love affair with her ex-boyfriend, who she renames after the Lachlan River: a body of water that her ancestor, the British explorer John Oxley, once believed led to a mythical sea at the dry, red heart of the country. The novel is, in many ways, about the hubris of mapping such narratives onto systems of violence, including colonial occupation and ecological disaster.

In different times, this interview would have taken place where so many of our best conversations have—over cheap red wine at a Greenpoint dive bar, while we took turns picking out American country songs to play on the jukebox. Instead, we spoke via Zoom, on opposite sides of the Atlantic—Watts in Berlin and me in New York, both of us far from the shared suburbs of our childhood. Like any conversation between friends, our dialogue was digressive and discursive. It has been edited for clarity.

*

Madelaine Lucas: When I was reading The Inland Sea, I thought a lot about the classic female coming-of-age novels that were important to me growing up as a young woman with literary ambitions, like The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath and Voyage in the Dark by Jean Rhys. Do you see The Inland Sea as a coming-of-age novel? In what ways were you writing into those traditions?

Madeleine Watts: The way the book started is very different how it ended up. Initially I wanted to write about a specific experience of young womanhood, one that was more complicated than what I’d been able to come across. I was always looking for echoes of my own experience in books because books were the most important things to me, and while I loved Sylvia Plath when I was a teenager, I didn’t encounter writers like Jean Rhys or Mary Gaitskill until I was writing The Inland Sea. I was interested in engaging with the coming-of-age novel, but the arc of a bildungsroman generally has the character coming to a kind of resolution at the end, a place at which becoming ends and adulthood begins.

It became fairly obvious to me in the writing process that the character in my novel was never going to learn anything and that I didn’t want her to.

It became fairly obvious to me in the drafting and revision process that the character in my novel was never going to learn anything and that I didn’t want her to. To some extent, it’s an anti-coming-of-age novel now because I was trying to reject any kind of redemption narrative. The narrator never really changes. Even though there’s some time in between the events in the book and her telling of them, it’s not reflective at all. It’s anti-reflective.

ML: The main character in The Inland Sea is also a little older than the Rhys and Plath’s heroines, who are 18 or 19. Your narrator is in her twenties and she’s recently finished university, but she’s just as formless. This felt so true to me—that you don’t come out of your teenage years “finished” in the way that the classic coming-of-age novel leads us to believe. There are other stages of your life where you feel completely lost or unmoored.

MW: I think that’s part of the experience of our generation. The tale of people our age is that we graduated into an incredibly bad economy and it never really got better. And now it’s much worse! All the life events that my parents went through, and all the things I had always assumed would give one a sense of security, don’t exist in the same way anymore. Being a teenager is oddly a less anxious period, I think, because when you finish high school there are more institutions to catch you as you exit. But if you go to university, then three or four years later you fall out into the world again, with no trust that there’ll be structures to catch you this time. That anxiety was much more frightening, for me at least.

ML: I noticed the word “safe” comes up a lot in The Inland Sea.

MW: Safety was something that I kept thinking about as I redrafted the novel and found it was becoming more about climate change. Around that time, I started obsessively reading about weather events and environmental catastrophes. When I was looking at these climate change stories—because they were all climate change stories—it felt almost like I was poking a bruise. It had something to do with not quite feeling safe, not feeling secure, but also trying to grapple with the idea that there’s no fix to this. The insecurity I was feeling, and still feel, will likely go on for the rest of my life, because that’s the situation we’ve created for ourselves.

ML: Your narrator has a complex relationship to fear. After taking a job as an emergency dispatch operator, she becomes afraid of just about everything but continues to court deliberately risky situations—like drinking until she blacks out and having unprotected sex with strangers. Can you talk about female recklessness in the novel?

MW: I was interested in writing about the experience of being a woman and the way that intersects with an experience of nature and landscape in Australia. A lot of that was a product of me reflecting on my own experiences growing up, and how I could see echoes of cultural fear threaded through the lives of the women in my family. There’s that famous Anne Summers book, Damned Whores and God’s Police, which I read when I was quite young, and it really informed my thinking about the roles available to white women in Australia—you could be virtuous and moral, or you could be a whore.

Reading stories about climate change has something to do with not quite feeling safe, not feeling secure, but also trying to grapple with the idea that there’s no fix to this.

Once I figured out that the book was about emergencies, I started thinking about how we respond to them. Emergencies tend to polarize people. You become very afraid. You can become radicalized. You can batten down the hatches and become quite conservative. The main character is working at Triple Zero, fielding these emergency calls where you never get the beginning, you never get the end, you just get 30 seconds of the very intense middle. It completely reduces her ability to think outside the absolute present moment. Being black-out drunk is one of the few ways you can mimic that emergency state because you stop recording memories. You have no past and you have no future. You’re all present tense.

ML: Female characters in fiction tend to get divided into a different kind of dichotomy: passive or self-destructive. I find that so limiting, especially because it doesn’t leave a lot of space to talk about vulnerability.

MW: The constant reiteration of the narrator being self-destructive is not something I ever thought about. She behaves kind of badly. She sleeps with some people she shouldn’t and she’s kind of selfish, but she’s not much worse than anyone else at 22 or 23 years old. There isn’t the same moral imperative behind the characterization of men—especially young men—behaving badly, or even realistically, whereas with women, you’re expected to justify it. I this is changing a little bit now with the popularity of things like Fleabag, but even then people tend to characterize characters like Fleabag as unpleasant or unlikable, making terrible choices. I thought she just seemed like a very real person. Like an intensely human human being.

I remember reading Little Women as a kid after having watched the film, and being shocked at how didactic the book was. At the end of every chapter there’s a little moral lesson, instructing you not only in manners and ideas of goodness, but also on how to be the 19th century’s version of an ideal woman. That Puritan streak to the judgement women in literature has never really gone away. Some readers have asked me to make moral assessments of the character in The Inland Sea, and I’m not interested in doing that, and I’m also quite surprised that it’s kept coming up.

The Inland Sea is not a moral book, but also women behave badly! We all know women who do. I wanted the book to inhabit a space of intense vulnerability, where the character doesn’t really know what she’s doing. I didn’t want to resolve that vulnerability, because when I was in that state, I would go to books to help me think and feel my way through it, and they were all like, “And then I fixed myself and got on my feet and got better.” I thought, but what if you just keep going? What if it doesn’t end? And it doesn’t. Vulnerability never ends. If you’re not talking about vulnerability, you’re just going to continue to have conversations that aren’t helpful and that don’t lead anywhere because people are going to make mistakes. People are going to drink too much and have bad sex and be wounded.

That Puritan streak to the judgement women in literature has never really gone away.

ML: At Columbia I took Rebecca Godfrey’s antiheroines seminar and something we spoke about a lot in that class was how to write an ending for a disruptive or unconventional female character. In classic literature, the unruly heroine is either “tamed” into marriage by the end of the book, or she is killed off and therefore punished for her bad behavior. So, how do you write an ending that resists those two pathways?

MW: There were books that I found really useful as models. Reading A Girl Is A Half-Formed Thing by Eimear McBride was important. I took a lot of inspiration from her ending, in which there is no redemption for the main character. The book ends with The Girl entering the water. My ending is less ambiguous than McBride’s, but there is a sense that both characters have lived in these liminal spaces the whole time.

While I was at Columbia I was working on the novel and came up against questions about self-pity, which I didn’t quite know how to get my head around. I had a very helpful conversation with Leslie Jamison when I was feeling overwhelmed by those questions, and she very wisely started talking to me about Jean Rhys. Afterwards I went straight to Book Culture and bought After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, Good Morning, Midnight and Quartet. In those books it’s nearly always a depiction of the same character who, you know, gets money from some man and then she spends it all on dresses and booze and then has to get more money from a man. Jean Rhys’s characters are self-pitying, but there’s a glassiness to them. They’re never trying to justify anything to you, and you don’t get promised that everything will work out. The Inland Sea doesn’t have the arc of a climax and resolution because I began to really hate those kinds of books as I was writing it. I hated the false imposition of logic on to a world when my world—the political and ecological and economic world I lived in—felt like one of complete chaos.

ML: At one point in the book the narrator’s ex-lover, Lachlan, says, “We are all the victims of the stories we tell ourselves.” In what ways is that true of the characters in The Inland Sea?

MW: It’s certainly true of the narrator and it’s also a cultural truth, more generally. That line came from a really early draft but in the editing process it began to take on a different meaning in connection to the environmental and historical theory I was reading, a lot of which was about the ways we choose to tell stories, and how those stories affect our ability to understand what we can see around us. That’s why, in the essayistic parts of the novel, I bring in anecdotes about the way previous cultures have interpreted natural disasters, as well as old kinds of apocalyptic and religious thinking, because those are all ways of making sense of the world. I remember being someone at parties who would fall into conversation and be like, can I tell you about a river that’s dying? For years I’ve just been a big bummer in social situations. I mean, you’ve been there!

ML: I can’t help but think of Joan Didion’s line from “The White Album,” “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” It’s been a while since I read that essay, but if I remember correctly, she is talking about a similar thing—using narrative as a crutch to make sense of the senseless. There is a side to that that can be really cathartic and healing, but that essay and also your novel are really alive to the ways the narrative impulse can do damage by justifying things that shouldn’t be justifiable, like, in the case of The Inland Sea, climate disaster and colonial violence.

MW: I was thinking about that Didion essay when I was writing The Inland Sea. The literature and thought of the early 70s was very much in my head and continues to be in my head. It helped a lot in terms of my thinking about narrative because I didn’t have such clear ideas when I started writing the book. I knew I wanted to write a novel because I loved novels and I grew up liking narratives because they all had narratives. But what was really appealing to me was getting introduced to books that broke narrative apart. It was a huge deal to me to read Renata Adler and William Gass, and then more contemporary writers like Ben Lerner and Jenny Offill.

When I was working on the novel, I was reading a lot of creative nonfiction. My copy of Notes From No Man’s Land by Eula Biss comes with me everywhere. It’s clearly my Desert Island Book because it was the one book I picked to take with me to Berlin. The way she structures something that has a flow and a shape but doesn’t conform to a narrative arc was so important. I was reading a lot of prose poetry as well, a lot of Anne Carson and Mary Ruefle.

ML: Did you have shape in mind for The Inland Sea when you started writing it?

MW: No, I wish I had. It took two big structural revisions after the first draft to find the right shape. I found myself constantly frustrated the whole time that I was working on it because I would write essays and feel so much happier with the writing I was doing. They felt freeing, in a way the novel wasn’t. I realized I had to try and take what was exciting me when I wrote those essays and put that into the novel. At that point, I did a really close read of Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill, which helped me figure out how she introduced fragments and bits of nonfiction in a way that felt seamless. Then I tried to re-structure my book to do something similar.

ML: I wanted to ask you about your revision process. How did you approach taking the novel through so many drafts while workshopping it in the MFA?

MW: I had to take a lot of time away from it. There were many months when I would try to write something else. Every time that I came back to the novel, it helped to print it all out and put it on the floor and move it around with my hands. On the computer screen, it has a linearity, and when you’re revising you have to let your brain loosen the joints between different parts and different sections. It helped so much to get scissors and sticky tape and have a tactile relationship to the book. I did that a couple of times once I realized it worked. I never did any handwriting. It’s too slow. I can’t do it. Partly, the problem is that I don’t think in a linear way. I can’t even tell an anecdote in a linear way. It was important for me to encounter the work of Rebecca Solnit when I was younger and see how the structure of her work mirrored the way that she thought.

Once I saw her read and I asked her, how did she structure these things? She said she just followed her intuition. She made the form fit the content of her brain. Whatever I write has to have the ability to circulate and have elastic joints, to make the content fit the flow of my own particular thinking. There are still bits and pieces of the book that I probably could have put in different places. Even towards the end, I feel like the prose still had a moveable quality. There is a way in which the revision process is partly battling your own demons, I think. You have to deal with the limited capacity of your own mind.

ML: That feels very accurate to me. I’m trying revise my own novel right now and I keep feeling like I’m just not smart enough to do it.

MW: Nothing makes you feel more stupid than writing a novel.

ML: It’s so true! For me, it feels like the work requires an intelligence that I haven’t yet acquired. But maybe that’s the project of writing. You’re always writing towards that intelligence or understanding you don’t have yet.

MW: I think you get through the new work by having hope that you’re fixing the problems that you know were in the last piece of work. And who knows, I’m probably still going to write the same things for the rest of my life. I think it’s fine for people to write the same kind of book.

ML: People have their subjects. The novels I love best always feel like the interior of someone’s mind and people have the same preoccupations a lot of the time—or even if they don’t, it’s all filtered through the same consciousness that’s going to pay attention to similar kinds of things.

MW: I agree with that. Every time I teach I tell my students that there are lots of different art forms that people can express themselves in now. Film and television, to a large extent, have taken over our narrative capacity. You can write narrative in literature, but it’s not unique to writing in the same way that it’s not unique to writing to express emotion because music can also do that. The one thing that literature can do that no other medium can is express interiority and express what it’s like to be inside someone else’s head. That feels like it’s strength. Inhabiting the consciousness of someone else feels much more exciting than reading like, Nancy Mitford talk about the problems at the country estate. Although that’s exactly the kind of narrative book that I want to read when I’ve got a cold, so it’s not like I’m completely anti-narrative.

The one thing that literature can do that no other medium can is express interiority and express what it’s like to be inside someone else’s head.

The writing I find most energizing borrows from creative nonfiction, even if it’s not necessarily autobiographical, like The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald. It’s all Sebald’s perspective and experience, but it’s not confessional. It’s fiction, but it’s also travel literature and history. It’s a really unclassifiable book. When I was in my early twenties I was very interested in the confessional. The confessional felt radical to me, in a political way. I still hold those opinions, but I also think that there is a kind of economy where women in particular are asked to put their personal experiences on a plate and offer them up to the world, and there’s not a lot of pay-off for that.

ML: I think I was also drawn to the confessional because I’m always looking for intimacy in whatever art I engage with. But reading Sebald, or Rachel Cusk, reveals that a text can still feel intimate without being confessional. I don’t think I really understood that until I read those writers.

MW: It’s the difference between something being first-person and something being autobiographical and something being confessional. I’m not as interested in the confessional anymore but I’m very interested in writing about bodily experience, and there’s a way the two can get conflated. I’ve seen some responses to the book that assume it is autobiographical, which I expected, but am still a little disappointed by. I think it comes down to the ways in which I lean in to writing in a detailed way about what happens to the narrator’s body, because there is an intimacy to writing about the body. There is an abortion. There’s quite a lot of sex, and there’s a failed IUD insertion scene. If that’s going to be construed as confessional, so be it. I think it’s important to read about what it’s like to inhabit the human body.

ML: What were the challenges of bringing those scenes to the page? The failed IUD insertion is particularly visceral.

MW: The failed IUD insertion scene and the abortion scene are twinned reproductive events. One could say it’s political to write about how women experience their reproductive potential, but I think it’s also just real. For women of a reproductive age, your reproductive cycle dominates your life. It does something to your experience of time and your feelings about how in control you are. It was hard to write those scenes and sit in those images. You find yourself wanting to write a sentence that makes it pretty, or gentler, because it’s confronting. In the same way with writing about sex, it can be easy to fall into cliché or nonspecific language, but the writing is always better if you strip away metaphor and simile because those are smokescreens. There’s also the question of how do you depict pain? Because even when you’re in the worst pain that you can possibly feel, all you can really say is “it hurts,” but then you also say “it hurts” when you stub your toe. You have to use pacing and rhythm and the internal sounds of a sentence to try and depict it. Those are the best challenges for writing, I think.

One could say it’s political to write about how women experience their reproductive potential, but I think it’s also just real.

ML: An important thread of novel is the affair that the narrator embarks on with her ex-boyfriend, Lachlan. How did you balance this storyline alongside some of the larger concerns that the novel grapples with, like ecological crisis and colonial violence? Did you ever worry these threads would compete for the reader’s attention?

MW: Yeah, I did, but you can’t have the narrator’s story without that relationship. If you take it out, then it’s just free-floating anxiety. There’s a lot of playing around with metaphor in the book in a way that is a little cheeky in its heavy handedness, but I was trying to find a way to talk about these things outside of the terms of the redemptive arc or the conventions of the realist novel. Allegory and metaphor were ways that I was thinking about writing. The allegory of the river that goes backwards, it’s about false belief. The Lachlan character is named after the river because the relationship is also a false belief, but it’s the thing the narrator uses to try to give herself structure—which also has something to do with narrative, and the way it isn’t enough to encompass the world we live in but we continue to seek it anyway. She keeps pursuing the relationship because, even if it’s a bad affair, it still has a narrative. She knows it won’t work out and that’s comforting. There’s a reliability to doing something bad sometimes. You know how it’s going to end, and that’s nice to know!

ML: I want to talk more about allegory and the environment. One of the epigraphs to the book is a quote from Judith Wright about how colonial Europeans perceived the Australian environment as “the outer equivalent of an inner reality.” This idea also comes up in the essay you wrote for The Believer about the preoccupation with lost children stories in Australian bush mythology. How did Wright’s thinking contribute to your own approach to writing landscape in The Inland Sea?

MW: The Judith Wright essay is called “Preoccupations in Australian Poetry.” I read it at university in a class I took called “The Australian Gothic,” which is probably the single most important class I ever took in terms of how I think about Australian literature and how I think about the environment. That essay defines the way that the environment has been construed as a kind of mental or emotional part of the Australian character in the art we make about it, and how that relationship has been produced by colonial violence, and codes of silence.

My experience of growing up in Sydney was one of taking the environment personally, but that line from Wright also felt important in terms of how I think we experience extreme weather now. On a basic level, the weather affects our lives and our moods. This past year in particular, I think everyone has been much more attuned to it. I’ve never heard so many people talk about the equinox with so much intensity. So, there’s that level, but there’s also the way in which, in Shakespearean plays and in the Bible, bad weather is caused by God. That idea is deep within the Western subconscious, and so I think it’s really natural to make these kinds of personal assumptions about weather.

ML: Something you capture in the book that felt very true to my experience growing up in Australia is the feeling that nature is always intruding. Tree roots cracking open the pavement, flying cockroaches coming in through the windows. The boundaries between outside and inside are not secure.

MW: I think that’s also very specifically Sydney thing. The fecundity of Sydney is more immediate when you don’t live there anymore.

ML: The Inland Sea was written while you were living in America, during a period where you did not go back to Australia for several years. In what ways did that geographical distance feel necessary?

MW: I think it’s personal as much as it is cultural. For both you and I, our families are over in Australia and once you move away, Australia becomes associated with one’s family. It’s really hard to think in a family space, is my experience. What do you think?

ML: At a distance, certain things become large and other things fall away. For me, what I don’t remember can be just as generative as what remains. When I go home, everything is dialed up so much that I feel like I can’t see anything. It’s only at a remove that I feel like I have the ability to gain some perspective, I suppose. I’m not confronted with the reality of that day-to-day experience, so my memories can become something more malleable or symbolic.

MW: You’re right about everything seeming more dialed-up. I remember when I went back for the first time after five years, everything was so intense. The smell was so intense!

ML: Oh, the smell gets me every time! Sydney smells really good, especially after you’ve lived in New York. Even just driving out of the airport, it hits you in the face. The smell of hot air and freshly cut grass and salt.

MW: And the sound of birds. It’s just cacophonous in this really operatic way. It’s like living in a Wagner opera.

ML: Thinking about the idea of the environment representing an inner reality, it occurs to me that this is also how we’re taught to read nature in literature—as symbolic. What problems does this present when writing about climate change?

MW: Part of what I was trying to accommodate in the book is our propensity to create those kinds of stories in our heads. Amitav Ghosh talks about the how the literary structures we have available to us from realist novels are not sufficient to deal with climate change. In the writing about climate change that I really enjoyed, nature is allowed to be a protagonist as much as the people are, but it’s an unknowable protagonist. You can’t understand nature because it doesn’t have motives. It’s humans who to give it agency, in the Judith Wright way—as the outer equivalent of the inner reality. We can make it mean something. We can make it feel malevolent, but it’s not. It’s just nature doing what nature does. In terms of writing about that, a book that was really important to me was MacArthur Park by Andrew Durbin. It starts with Hurricane Sandy and this incredible writing about apocalyptic thinking. The impact of the hurricane continues to be felt as an emotional ripple throughout the rest of the book, even as it leaves New York and travels to London and LA, without adopting the hurricane as a structure with a climax and resolution.

I wouldn’t tell every writer that you have to write about climate change because it’s the biggest thing that we’re facing, but I do think it presents a challenge to the way that we write books and the way that we write in general, because writing about one event or one individual, is not quite enough to capture what it’s like to be alive right now. You need a way to hold a collective as well as an individual experience. Alice Bishop’s book A Constant Hum, about the Black Saturday bushfires, is a good example. You get a really good sense of that particular climatic event through a chorus of voices. That was what I tried to use the emergency calls in The Inland Sea to do—to act as a chorus.

While I was working on the book I was reading a lot of nature writing and I felt frustrated that most of the novels about climate change were marketed as science-fiction or futurist because they deal with the cataclysm after it’s already happened—you know, ten years the future when the ocean has already risen. I wanted to write about what it was like in my lifetime. What is happening with the environment is a catastrophe that’s happening really slowly. We’re not used to that kind of timescale, especially now.

ML: In a recent essay for this website on your relationship to plants and nature in your daily life, you write, “There is no neat happy ending to be found in this story, no arc of redemption. But everything we can possibly love, in all its brokenness and beauty, is here.” It struck me that there was more tenderness in your writing about nature here than in The Inland Sea—and maybe even a tentative hope. Has your thinking and writing about the environment changed since writing The Inland Sea?

MW: Yeah, I think it might have changed. I don’t see apocalypse in everything anymore. I feel like I’m more in touch with how utterly dependent I am on the natural world, in a way that quarantine has really brought home. I put a lot of faith in the ability to pay attention now, and to think less perhaps about the outcome, and more about the day-to-day. There is some hope in that, I think.

__________________________________

The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts is available now from Catapult. Copyright © 2020 by Madeleine Watts.

Madelaine Lucas

Madelaine Lucas is the author of the debut novel Thirst for Salt and a senior editor of the literary annual NOON. She teaches fiction at Columbia University and lives in Brooklyn with her husband and her dog.