Voices of the People: On Folk Music as a Living Art Form

Ellen Harper Remembers Her Mother and the Gift of Making Music

My life has seen an endless flow of musicians, activists, and artists eddying through my home and the Folk Music Center my parents founded and I maintain today. Some were musicians who played and sang for a living. Others played and sang for the sheer joy of it. They were working people, union people, family people, and traveling people. Some had money and some were broke.

Some had recognizable names—Doc Watson, Jean Ritchie, Hedy West, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Pete and Mike Seeger, Joan Baez—but most did not. What all these musicians, music lovers, pickers and players, songwriters, painters, poets, dancers, political activists, and their husbands, wives, and children had in common was singing. Singing was essential. Everyone’s voice mattered, regardless of fame, or skill, or any other label. Community mattered. We were all singers, and singing could change the world.

My mother, Dorothy Udin, gave me a great gift: the world of folk music and folk musicians. She sang me to sleep with mournful lullabies from eastern Europe, the British Isles, and the American South. She taught me the power of music through the work of great folk singers and musical ambassadors such as Pete Seeger and his American Folk Songs for Children and Woody Guthrie’s Songs to Grow on for Mother and Child—the joyous, raucous albums that inspired and empowered me. I grew up listening to her giving music lessons. My ears were filled with the music of hootenannies and song circles, the glorious sing-along music of the union, civil rights, and antiwar movement songs, along with the blues, hymns, and gospel tunes that undergirded them. I took up the guitar and learned to play the songs I had been singing my whole life, including the beloved folk classics “Gold Watch and Chain,” “Goodnight, Irene,” “So Long. It’s Been Good to Know Yuh,” “Single Girl, Married Girl” “Midnight Special,” and dozens more.

I developed my own musical passions. I embraced the music of my generation—folk rock, rock and roll, and psychedelic rock. I joined my fellow musicians and explored the sources of our music, such as Delta blues and country music. I discovered that all these genres grew from the same roots, the music of generations of anonymous musicians who made music for their lives and communities, the music that we call folk. Not the commercial-variety folk music that bloomed and faded in the 1950s and 1960s, but the legacy of the voices of the people expressed in poetry and lyrics that shaped my life, my musical taste, my style, and ultimately the music of my children. Throughout my life the traditional folk songs I learned at my mother’s knee have always been in me, old friends that speak the wisdom of the ages as I faced new challenges.

Folk music is a living art form that tells and retells its history, even as it creates it.

Folk music is a living art form that tells and retells its history, even as it creates it. As with any vital art form, there are passionate debates. The very term folk song is contentious. Blues musician Big Bill Broonzy, upon being asked “What is folk music?” is purported to have answered, “All music is folk music. I ain’t ever heard a horse sing,” a comment that unleashed a decades-long feud among musicologists about the origins and definition of folk music.

Ultimately it doesn’t matter. What matters is that the music lives on, enriching our lives. We know enough. We know that American folk music originated in the oud strummers of the Middle East; the lute pickers of Europe; the balladeers and bawdy pub singers of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Brittany; the fiddle bowers of eastern Europe; the n’goni pluckers of Africa; the chants, plaints, calls, and hollers that came from everywhere to the New World, bringing lyrics, melodies, marches, and polyrhythms that invented and expanded the American musical horizon forevermore. No matter how much Americans tried to segregate themselves, the music ignored boundaries and slipped in and out of parochial communities, creating something bigger than the sum of its parts: American music. The folks who created folk music borrowed, stole, shared, and learned from each other until the music became something distinctly American, something that went on to influence world music, which in turn influenced American music.

For me, a good song is a good song. Defining folk music is best left to the experts; it is a rabbit hole I’d rather avoid. What matters are the songs, which connect us across generations and cultures. What matters is the singing.

The community and the social and political activism that are as integral to folk music as the music itself are woven throughout my story—our story. It begins in New England during the early days of the folk music revival and travels through the fear and hatred of the McCarthy-era blacklist that drove so many nonconformists, bohemians, leftists, and ordinary people who believed in a better world—including my father—out of their jobs and underground. Forced to leave our home, we moved to the West Coast, and my parents founded the Folk Music Center and went on to play a vital role in the 1960s folk boom that impacted the counterculture and its music—influence that reverberates to this day.

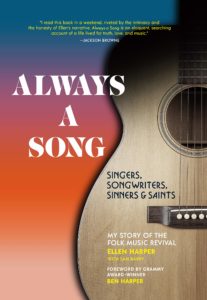

Always a Song is the story of the challenging, transformational times in which I have lived, loved, and sung, from the dawn of the age of the singer/songwriter as the premier artist and the guitar as Western music’s dominant instrument, accompanied by the popularization of new, “exotic” instruments such as the sitar and the ukulele and the legacy of love-ins and decades of protest movements. Always a Song is my witness of the world of folk music that is the fuel and inspiration of American music. It is the story of the extraordinary times in which I have lived and the people who have flowed through my world with a song for every reason—songs about hardship and good times, songs of love and loss, songs of hope and hurt, songs of endurance and solidarity, and some songs just for fun—but always a song.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Always a Song: Singers, Songwriters, Sinners, and Saints: My Story of the Folk Revival by Ellen Harper. Copyright © 2021. Reprinted with permission of Chronicle Prism, an imprint of Chronicle Books.

Ellen Harper

Ellen Harper is a singer, songwriter, musician, and owner of the Folk Music Center. She released her first solo album in 2018, Light Has a Life of Its Own, at the age of 71. Ellen and Ben Harper collaborated on the album Childhood Home and went on tour together in 2014. Ellen lives in Claremont, California.