Vocal Effects: How Hormones Change the Way We Sound

Carole Hooven on the Role of Testosterone in Human Speech

Testosterone and related androgens (and also estrogen) direct the body’s energy to be used to build up molecules and tissues, while other hormones, like cortisol and adrenaline, break down tissues and molecules to free up energy to fuel working muscles, among many other functions. Growing and remodeling the tissues of a boy into those of a man is no small feat of physiology. Accomplishing such a metamorphosis requires lots of energy, and it also requires tight coordination between the reproductive, nervous, endocrine, and metabolic systems. T is like the foreman of this massive construction/remodeling project, relying on a cadre of workers with different skills, and the right connections to ensure the smooth supply of a variety of materials. T recruits a team of hormones, including growth hormone, estrogen, insulin, and thyroid hormone, to help out, since they all have different areas of expertise. In general, these all play a role in deciding which tissues have priority at any point in life (e.g., growth hormone for childhood growth, T for muscle development in puberty, and progesterone to support uterine function in pregnancy). With T’s oversight, the team can ensure that the right materials get deposited at the right times and in the right places for male reproduction.

Stopping the action of testosterone won’t undo all its earlier work, even when supplemented with high doses of estrogen. Imagine building a brick house. Once they’re up, the brick walls require little upkeep, but they are also difficult to renovate. The rest of the property, however, requires maintenance—regular painting inside and out, changing the AC filters, repairing the roof, watering the lawn. The construction projects directed by T are of both kinds: those that involve permanent changes requiring little upkeep, and those that need ongoing attention. Developing a boy’s bone structure into that of a man, including growing the long bones, masculinizing facial bones like the jaw and brow ridge, or lengthening the vocal cords or, as specialists call them, “folds,” are like building the brick structures, which are strong and stable but difficult to alter or tear down. But enhancing upper-body musculature, developing the reproductive system, and redistributing fat are like painting the siding and installing air-conditioning. Without maintenance and repair overseen by the T foreman, these other features will lose some of their previous function.

Testosterone’s bricklike effects are the reason that physically transitioning in the male-to-female (MtF) direction is so much harder than the reverse (FtM). Many of the secondary sex characteristics that T produces in puberty, like broad shoulders, square jaw, and greater height, are obvious cues to the male sex and are difficult to eliminate or even significantly remodel or reduce.

*

Castrati were young boys with promising singing voices whose testicles were removed prior to puberty in order to prevent the development of an adult, masculine voice. Without the high T of male puberty, they retained the ability to hit the high notes.

The quality of a person’s voice, including breathiness, pitch, and intensity, provides others with a surprising amount of information.

My 11-year-old son still sounds like a boy. When his voice deepens in a few years (usually around an octave), its sound will signal to me and everyone else that his boyhood is over. The quality of a person’s voice, including breathiness, pitch, and intensity, provides others with a surprising amount of information—about sex, age, health, social status, even the stage of a woman’s menstrual cycle. A deep, strong voice is a potent signal of adult masculinity, sexually attractive, and a signal of dominance to other men.

Meet Kallisti, a trans woman. She transitioned in the opposite direction from Alan, from male to female. But she did this in her early thirties rather than at 13, and so endured the full suite of changes wrought by male puberty.

As a kid, I loved trying on my mom’s clothes. I knew something about the way I was gendered was incorrect, but the people who told me I was a boy were in charge of things, important things like paying the bills etc., and I listened to them. But I knew it wasn’t right. It wasn’t really the clothes themselves. I think I understood even then they were just a costume. But as an actor, I know that a costume can act as a shortcut to expressing something deeper and richer. For me, that was the innate feeling that I was a girl. The clothes helped me to inhabit that feeling, express it. And it just felt… right. I felt somehow more myself.

Testosterone definitely had serious effects and influences on me when I hormonally transitioned as an adult.

Alan wished he could have experienced male puberty a little earlier to gain more height, and while Kallisti is a proud six-foot-four trans woman, her life would have been made easier had she not grown quite so tall or developed a masculine bone structure.

Puberty also gave Kallisti a deep voice. Although she can feminize it to some extent through voice therapy (as many trans women do), it still cues masculinity. I had to make an effort to override the masculine signal her voice sent over the phone, and it was easy to see why this could make life difficult for Kallisti.

The changing levels of several different hormones throughout our lives, such as estrogen, progesterone, growth and thyroid hormone, affect the quality of our voice by acting on the vocal anatomy, most prominently the larynx, otherwise known as the voice box. But none are as impactful as male levels of T in puberty, which are 20 to 30 times higher than in females of the same age. (The effects of sex hormones on the female voice during this same time are small, particularly compared to those during and after menopause when hormonal changes can cause the voice to become huskier.)

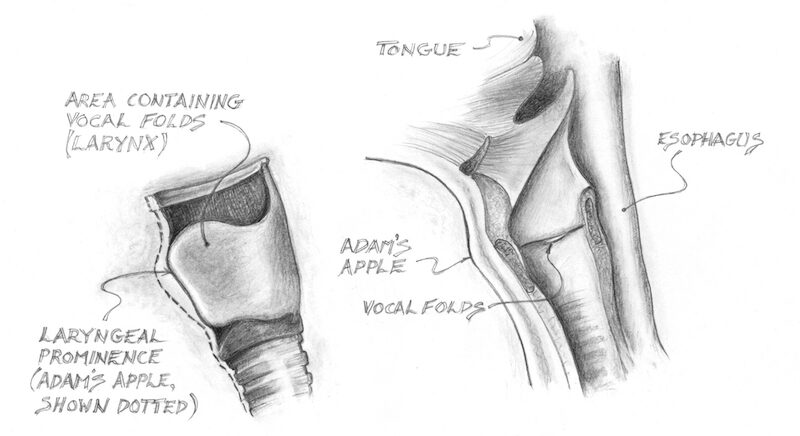

You can picture the larynx as a tubular structure at the top of your neck. Its base connects to your trachea (windpipe), another tube-like structure, that runs down from the larynx into the chest cavity before it branches into your lungs. The whole system allows air to pass between your lungs and through your nose and mouth; the larynx also acts as a valve that closes off the airway to protect it when swallowing. All this tubery is obviously crucial to your survival, but it also allows you to modulate the airflow so you can speak, shout, or sing.

Vocal tract. Illustration credit: Felix Byrne.

Vocal tract. Illustration credit: Felix Byrne.

Inside your larynx are your vocal folds, a pair of short rubber-band-like tissues that stretch across it. We can manipulate our vocal folds to affect their rate of vibration and the sounds that can be produced. By relaxing and contracting the muscles that are attached to the folds, we can alter the folds’ shape, tension, and the amount of space between them, sort of like a pair of lips stretching, closing, and opening. The tissues of the larynx are rich in androgen receptors during male puberty, and T interacts with its receptors to elongate and bulk up those tissues. Among other effects, T causes the diameter of the larynx to increase, creating a wider tube, and it also causes the vocal folds to thicken and lengthen.

The length and thickness of the vocal folds are important determinants of the depth of your voice. If you play a string instrument the principles will be familiar, but if you don’t, take a rubber band, stretch it tight between your fingers, and give it a pluck. Then pluck it again when it has more slack and is thicker. You can also experiment with the length of the rubber band. Longer and thicker strings, bands, or cords vibrate more slowly when stimulated, producing a lower pitch, and shorter, thinner ones vibrate more quickly, producing a higher one.

Cross section of larynx with vocal folds. Illustration credit: Felix Byrne.

Cross section of larynx with vocal folds. Illustration credit: Felix Byrne.

Other T actions also help masculinize the voice, like building up the ligaments and muscles in the larynx and growing bones in the face to produce larger nasal and sinus cavities. T also acts to lower the position of the larynx in the neck during male puberty, giving the voice lower resonances (called “formant frequencies”). These changes all make it possible to project the voice more loudly.

T’s actions on the vocal folds can’t be undone by blocking T or taking estrogen later in life. Once thickened and elongated, the only way to bring them back to their previous state is vocal cord surgery. But the path to a manly-sounding voice is relatively smooth for FtM transgender people, no matter the age at which they start their hormonal transition. The voice will begin to drop within two to five months of starting male levels of T and will stabilize within a year. But it may never reach the same depth as that of a natal male.

This is because after the pubertal growth and remodeling of a natal female’s body, high T, introduced later in life, can thicken the vocal folds, but its effects on the larynx are more limited (similarly, wide hips cannot be narrowed). As a result of having gone through female puberty, the diameter of the larynx is relatively narrow, and high T after the fact doesn’t appear to widen it. So the length of the vocal folds is restricted because they can’t stretch across a wider larynx. The smaller size of the larynx, vocal folds, and resonating chambers, like the chest and nasal cavity, can all constrain the ability to achieve a deep, powerful voice. But overall, most trans men are satisfied with the vocal changes that T brings.

__________________________________

Excerpted from T: The Story of Testosterone, the Hormone that Dominates and Divides Us by Carole Hooven. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2021 by Carole Hooven. All rights reserved.

Carole Hooven

Carole Hooven, PhD, is lecturer and codirector of undergraduate studies in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. She earned her PhD at Harvard, studying sex differences and testosterone, and has taught there ever since. Hooven has received numerous teaching awards, and her popular Hormones and Behavior class was named one of the Harvard Crimson’s “top ten tried and true.”