Visiting the Old Country by Way of Kew Gardens, Queens

Jane Ziegelman Remembers Dinners at Her Grandmother’s

My grandmother lived in Kew Gardens, Queens, an hour by car from our apartment in Manhattan. The journey took us up the West Side Highway, across the lower part of the Bronx, and over the East River. Since most of our visits revolved around dinner, the drive usually took place during the evening rush hour. Really, it was just an average New York commute, but for me it meant stepping out of one reality and into another.

Among the regulars at these family dinners were my grandmother’s three brothers, their wives, and a scattering of their children and grandchildren. To accommodate everyone, a T-shaped configuration of tables was set up that ran the length of my grandmother’s living room. Simply but festively set, the entire T was draped in white tablecloths and adorned with bright blue and green seltzer bottles, the kind with spigots. Getting the seltzer to flow from them took some finesse. Squeeze the handle too lightly and the bottle would sputter and hiss but release nothing. Squeeze too firmly and the seltzer would hit the bottom of the glass and splash back out, prompting a chorus of “not so hard!”

The room was well-lit, which gave the illusion of spaciousness. Once the meal began, however, and people were seated, to get up from the table you had to shimmy out sideways, except for the children who were able to slink out on hands and knees. Our dinners were multicourse affairs that lasted for hours. Mid-meal, my sister and cousins, tired of all that sitting, would decamp to my grandmother’s room with its two single beds spaced at just the right distance for leaping between. That left me, the one remaining kid at the table, free to concentrate on whatever the adults were talking about.

My grandmother and her three brothers had emigrated to the United States from a town in Poland called Luboml. They came one by one, starting in the 1920s with Shloime (pronounced SHLOY-meh), the oldest, followed by Harry, then Nathan, the “baby,” and finally, Esther, my grandmother. When discussing their departure, they never said, “I left Poland in such and such year.” The phrase they used was “got out,” as in “that was the year I got out,” alarming words, even to a ten-year-old.

My relatives were as mysterious to me as the people we learned about in social studies.

All three brothers found jobs in the New York fur industry. Eventually, Shloime segued into real estate, paving the way for my father, but Harry and Nathan stayed in fur for the rest of their working lives. Nathan dealt in “small furs,” scarves, stoles, and capes made from mink and stone marten, while Harry became a “mouton specialist.”

A fancy-sounding word for sheared sheepskin, mouton was relatively inexpensive and very warm but considered down-market. Knowing how beautiful it could be, and seeing what other manufacturers were doing with it, made Harry crazy. “It’s a crime,” he’d say. “They’re interested only in making a front and a back with a pair of sleeves. The garment needs a little styling!” In the realm of mouton, his innovation was to use only the most flexible skins, which gave his coats a svelter, more modern silhouette. As a college student in the 1980s, I weathered the cold Ohio winters in one of Harry’s mouton creations, an espresso-brown coat with a black satin lining.

My relatives were as mysterious to me as the people we learned about in social studies. By the early 1970s, they had been living in the United States for at least three decades, but they were nothing like the people I was surrounded by on the Upper West Side, Jews as well, many of them, but very much assimilated. The siblings spoke a heavily accented version of English in which w’s sounded like v’s and r’s rumbled, like someone imitating the roar of a lion. English sentences often followed the rules of Yiddish grammar. “You want I should give you some fish?” my grandmother would ask. When a word was untranslatable, they resorted to the original Yiddish.

One word I learned from these dinners was nebakh, which means something like “such a pity.” It usually came at the end of a sentence, as a kind of exclamation point: “The doctor said it would heal as good as new, but she never walked the same again. Nebakh.” Nebakh was also used to cut off a sentence midstream when the speaker felt too overwhelmed to continue.

I remember once asking my grandmother about the food in Poland, what did they eat when she was a little girl. Before answering, she looked at me as if I had asked her what color the sky was in Luboml. “Eat? We were five children. We ate soup, soup with potatoes, with noodles. My mother was a very good cook. She could make a soup from anything. From weeds that grew by the road . . .” Here, she shut her eyes tight and shook her head. “Nebakh . . . nebakh,” she said, and that was the end of the conversation.

Out of all the siblings, Shloime was the most observant. Though he earned his living as a New York landlord, by vocation he was a scholar of Talmud with his own flock of disciples. Like other observant Jews, he kept his head covered as a sign of religious devotion. Shloime was never without his hat, a black fedora with a narrow brim and small red feather sticking out of the hatband.

Except for my father, all the men in the family wore fedoras, but Shloime was the only one who kept his on while eating. He was a distinguished person, one foot in real estate, the other in a remote, spiritual realm. Shloime had met his wife while living on the Lower East Side shortly after arriving in New York. As deeply pious as her husband, Necha was an amazingly small person with a wizened face who looked as if she’d spent her life in the fields. Her most unusual feature was her teeth, which were crooked in a way that reminded me of a spiral staircase.

Her cooking was like the rest of her, refined, meticulous, elegant.

My great-uncle Harry had a booming voice and thick, steel-gray hair, which he combed straight back and held in place with Vitalis, like a 1930s movie star. His eyebrows were dramatically arched, like two furry circumflexes, which made him look as if he was always about to ask a question. Harry dressed in double-breasted suits and shirts with cufflinks. His wife, Rose, also flamboyant, was a bottle-blonde with a taste for frosted lipstick and earrings reminiscent of door knockers.

My grandmother and her siblings were deeply devoted to one another, more so, it seemed, than to their own spouses. The brothers adored their only sister and doted on her, and in return she catered to them, literally. My great-uncle Nathan had remarkably full lips, almost purple in color. A heavy smoker of Kent cigarettes, he had some unusual food quirks. Most notable was his aversion to onions, an ingredient found in just about every Jewish dish you can think of.

Each December, at Hanukkah, when his wife, Dorothy, made him latkes (potato pancakes) with onion, he refused to even taste them. “But you can’t make latkes without onions,” she used to say. The one person who could perform such a feat was Esther. Between my grandmother and the rest of womankind there was no competition. She was the exemplary woman, beautiful, loving, pious.

My grandmother’s uniform was a silk blouse, the kind with buttons down the back, which she tucked into a straight skirt made smooth by a girdle. Her hair was always “done,” an hours-long process that involved curlers and a rattail comb. Her accessories were tasteful: pearls and a brooch. Though only 5’3″, she had the posture of a duchess, which made her look taller than she was and which she maintained deep into old age, even in the wheelchair that served as her throne at the end of her long life.

Her cooking was like the rest of her, refined, meticulous, elegant. Her chicken soup was the color of sunlight, her gefilte fish was as delicate as a French quenelle, her latkes were evenly browned.

Esther was revered for her outstanding cooking ability, and as the bestower of food, we were all indebted to her. Her ability to exact fealty through nourishment was something that impressed me, so it seemed natural that as I became more interested in cooking, I would turn to her as a role model. Someone who cooked from muscle memory, never with a recipe, she had her own nonstandard way of giving directions. “You take a carrot, and you rub it,” meant “grate one carrot.” “Put it to the flame,” was her way of saying “sauté.”

Most of what she prepared for us she had learned to make in Luboml. The menu was consistent from one dinner to the next: gefilte fish crowned by the mandatory slice of carrot, followed by chicken soup, potato kugel, roast chicken, and her signature achievement, roast breast of veal, stuffed with challah or matzoh, depending on whether or not the meal took place during the eight days of Passover. Her one concession to American cooking was “salad,” which consisted of iceberg lettuce and green peppers tossed with lemon juice and Wesson oil.

The word she used to describe her cooking was “plain,” a legacy, I believe, of old-world fears about the dangers of vanity. Raised in a culture where advertising one’s talents was an invitation to the evil eye, she was careful not to boast. It’s true, the only seasonings in her kitchen were salt, pepper, onion, paprika, and the occasional scattering of fresh dill. However, minimalism was her asset. The flavors she managed to coax from a few simple ingredients were deep and pure, which she knew as well as anyone.

The relatives ate with a mixture of businesslike efficiency and gleeful abandon. Picking up a drumstick and gnawing it clean, past the cartilage and down to the bone, was accepted without a second look. The same went for veal bones, which left such a sticky residue on your fingers that when you tried to pat them clean, the napkin would tear.

The point being, I couldn’t have told you why my relatives sang at the table or what they were singing about, each melody delivered with mounting gusto.

Some bones, however, were pliant enough to receive special treatment. The relatives—males only—would grind these in their teeth until achieving a mulch-like texture, then spit them neatly back on the plate, all so expertly executed that it never struck me as unappetizing.

The final course was Tetley tea served out of glass cups, always with a slice of lemon that turned the tea a pale amber color. Instead of sweetening it, the relatives clamped a sugar cube between their incisors and loudly sucked the tea through it. As they continued drinking, the cube slowly dissolved, so by the time the cup was drained it had melted away completely. It was during the tea course that the men at the table would begin to sing their afterdinner hymns, their voices accompanied by vigorous table tapping.

I should explain here that my immediate family was not at all religious. My mother didn’t keep a kosher kitchen, and we didn’t observe the Sabbath. My sister and I were getting a secular education at an outrageously progressive school on Central Park West. On weekends, we attended Sunday school at a reformed Manhattan synagogue led by one of America’s first female rabbis.

What I remember most clearly about Sally Priesand is that she had lanky brown hair, like Joan Baez, and wore glasses shaped like stop signs. Under her guidance, we read bible stories and performed the “vine step” in Israeli folk dances, but learned very little about the rituals and observances that fill the everyday lives of religious Jews. The point being, I couldn’t have told you why my relatives sang at the table or what they were singing about, each melody delivered with mounting gusto. To my ten-year-old self, it was a musical performance filled with secrets and suspense.

Suffice it to say our dinners were high-spirited affairs. In addition to the obligatory singing, there was abundant conversation. Sometimes, the relatives talked about Poland, what life was like there. They remembered details about their former home and recited them easily—which neighbor lived on the right and which on the left, the name of the butcher, the way the water froze around the pump in winter.

At times, they would turn to us, the kids, and tell a story: When the siblings were children themselves, the family owned a cow. She was a notoriously mean animal, who kicked viciously when people tried to milk her. The only person who could get near her was Shloime. In summer, when she was most productive, their mother made sour cream, which they spread on slices of rye bread. A gourmet treat. In winter, they brought the cow into the house as a heat source. “You see, she was our furnace!”

Over the years, they told the same stories over and over until we, the children, could recite them ourselves. “When I was a youngster,” Nathan used to tell us, “I followed my mother everywhere. I wouldn’t let her out of my sight. Sometimes she would walk to a neighboring town to sell something. Well, I insisted on going with her, two miles there and two miles back. Quite a walk for a little fellow!”

Our family stories were like those holographic pictures that came in Cracker Jack boxes. Tilt them back and forth, and they flickered between two distinct images. Balance them just so and it was possible to see both images at the same time. Like the story of the housebound cow, which I knew was told to amuse us. A tilt in perspective, however, and it became a tale of stark poverty, the family too poor to afford wood for the stove. Then there was Nathan, the dedicated son. Tilt and the gallant escort was replaced by a boy too traumatized to leave his mother’s side.

I had seen flashes of that beauty at our family meals, as the men sang, faces flushed, and the women drank their tea.

At home, my sister and I had a copy of D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, which was where I first read about the goddess Demeter and how she had cursed the earth. I imagined that something similar had happened in Luboml, that it had been cursed, and the people who lived there were doomed to unhappiness. A person’s only hope was to leave, like my relatives who were lucky to have “gotten out.”

My problem was how to square that with something else the relatives impressed on us. In Luboml, a person would do anything to help another, family or friend; there was no limit. That willingness is what the siblings called “devotion.” To describe someone as “devoted” was the highest accolade, on par with “learned.” Nowhere on earth could you find people so devoted as the Jews of Luboml.

I had reason to believe that by the time I was born Luboml no longer existed. No one ever said, “I hear they’re paving the streets in Luboml,” or “I’m considering a trip to Luboml.” All discussion about Luboml was conducted in the past tense. Luboml belonged to a different time when life was both harder and more beautiful. I had seen flashes of that beauty at our family meals, as the men sang, faces flushed, and the women drank their tea. The great mystery for me was how and why Luboml had met its end. On this subject, not a word was uttered by any of the siblings.

I spent many hours as a kid wondering about my grandmother’s eyes, why they didn’t stop tearing, and Nathan’s dark moods. I’d learned to tread carefully when talking about Poland, a subject I was enormously curious about, but was never sure which questions I was allowed to ask and which were forbidden. As it turns out, the stories I wanted to hear were contained in a yizkor book that was sandwiched into the bookshelf in my parents’ bedroom where it sat, undisturbed, for decades.

__________________________________

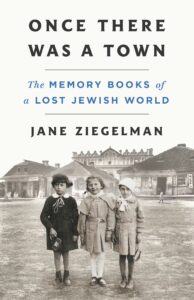

From Once There Was a Town: The Memory Books of a Lost Jewish World. Used with the permission of the publisher, St. Martin’s Press. Copyright © 2025 by Jane Ziegelman

Jane Ziegelman

Jane Ziegelman is the author of the classic 97 Orchard, and coauthor of the James Beard Award winning A Square Meal. She lives with her husband in Brooklyn, New York.