In the dream, someone removed her arm and shredded it like a block of cheese, and it would’ve just been a creepy nightmare if she hadn’t woken up with dirt in her bed. A handful of dirt, in a little pile, around the knee area.

I would’ve noticed this in the daytime, she told her boyfriend. I would’ve seen this in my clothes.

It’s such tidy dirt, he said. Who makes dirt into such a nice pile?

They used the hand vacuum.

An animal? She didn’t have a mobile pet, just a few tanked fish.

The second dream was about her legs being cut into strips like pieces of flank steak. She wouldn’t have even remembered these dreams if something of them hadn’t been waking her in the middle, bleary-minded, clock redly stating 4:02, but she found herself this time with a pile of gray silt in the bed, also around the knees, the material softer, no boyfriend sleeping over. She sat up, ran her fingers through it, the apartment so quiet and still around her. She didn’t want to dispose of it because the dirt itself might have some value, seemed dredged from bits of ancient shells, so she scooped it with care into a glass jar that once had held mustard, vacuumed the rest, and scrolled on her phone until light seeped in beneath the blinds.

After breakfast, she decided to go see her grandfather, who concerned himself with matters such as these. She hadn’t seen him in many years but his office was not far, a short bike ride away. He’d spent his whole academic life studying dreams.

He was surprised to see her but welcomed her in warmly and listened with steely eyes, stirring a glass of water into which he had emptied a powder.

So in the dreams, you are in lines, he said. Shreds, strips. In the bed—?

Particles? she said, trying to follow his thinking. Dusts?

Dirt, then silt. Well. He took a sip of his drink, made a face. Terrible, he said, speaking of dirt. You know about the rule of three? Surely there’s another dream coming soon. But what follows silt?

He took a breath like he was going to dive underwater, drank the glass down, and then rinsed the cup at his sink and refilled it.

Pure water, he said. Now there’s a miracle. Anyway, it’s wonderful to see you. Please, return anytime. Definitely after the third.

The third seemed to have been scared off by all the build-up, so it was weeks until she had another, this time her body sliced in half, into two symmetrical pieces, each pierced and then roasted on a spit. Why, she found herself wondering in the dream, rotating, do I keep offering myself up as food?

In the bed, a glop of mud. It looked like a shit until she built up the nerve to smell it and then it spoke of the deep dark earth, like something anything could grow in, fertility made material. She got up, washed her hands, gathered the sheet, and took the mud to the side strip of yard, where she dumped it on the dirt, and then took the sheet straight to the laundry room and washed it on “extra-soiled.” It was early; once again, she biked over to see her grandfather. He ushered her into his office as a young man with red tear-stained eyes hustled into the elevator without looking at her.

Mud, she announced.

I’m so glad you returned, he said, steepling his fingers. I was hoping. Mud. Interesting. What do you think?

I turn into these things? she said. After some time, I too will become dirt, silt, mud?

True. But that’s a long wait. You were roasted on a spit?

Yeah.

Are you aware of who will eat you?

Nope, she said. No one’s around. I don’t really think anyone is going to eat me.

He pursed his lips. If there are additions in the bed, perhaps there are vacancies elsewhere. Can you look for vacancies? Do you have a garden?

Listen, she said. Why did you leave my mother? As a toddler? That fucked her up so bad.

Her grandfather coughed. His steely eyes, formerly clear as split glass, turned lake-like, opaque. I was a young and reckless man, he said. I could not possibly have been a father.

She revered you, said the young woman. She had, like, an altar to you in her bedroom. She said she would literally pray you would visit.

He was silent for a few minutes. It is terrible, he said. How unknowing a person can be of the pain they’re inflicting. I was entirely absorbed in myself.

He raised those lake eyes to her. They were old eyes now, framed in crinkles, his face aged, his hair white. She’d only seen a few photos of his younger self in albums hidden away that her mother would bring out on holidays when she was feeling particularly morose. He did resemble her a bit, she could see that, in the face shape, even in the eyes themselves. Her mother adored her, and it was real, but a tiny part, she knew, was because she looked like the absent father and could accept all the love he never gave.

You owe us, she told him, but it wasn’t full of conviction.

No, her grandfather said. I can never repay. But I can try to help you. He reached into a desk drawer and removed a smooth gray stone.

Put this under your pillow, he said. See what happens. It’s a stone from my own childhood. I used to live near a creek, in Washington, on an island. I’ve carried this with me everywhere, every single place I have lived or worked. If it has any bearing, it will help. It means a great deal to me.

She held it. Smooth, almost rounded, with a stripe of white across the far side.

You want it back?

I suppose not, he said. It causes me a little pain to give, so maybe it’ll be worth something to you.

She laughed.

At night, with the stone under her pillow, she fell asleep fast; it had been a busy day otherwise, with work, and jogging, and dinner with those talkative friends who were so funny but then also exhausting.

This dream was different. She was not to be eaten. She was eating noodles in a sauce, the bowl changing size from small to huge and back again. She was high-fiving someone playing basketball in the distance with a giant hand. The noodles were full of laughter.

When she awoke, the stone was gone. A few pebbles had gathered by her feet, little gray ones, as if the stone had broken into pieces and traveled down the length of the bed and somehow eroded enough to be worn smooth again.

She brought the pebbles into the office, let him hold them.

Not sure if they’re the same, she said.

I see no white lines, he said, peering with his reading glasses on.

You played basketball? she asked, and he said yes.

I think I met you, then. We high-fived.

He blushed a little. I was never very good.

He told her he had been thinking. About leaving his child, about how that had shaped her life and her mother’s.

My own father, he said, drumming his thumbs on the desk, was very demanding and rarely pleased. A difficult man. I maybe thought it would be a relief not to have someone like me around, even though I am not like that. Maybe I was worried I might turn into him?

Well, she said, playing with a glass paperweight. That is dumb reasoning. It was not a relief.

She swiveled her chair to and fro.

You talk to people all day?

I do.

They tell you their deepest secrets?

Some do, he said. Some lie. Some tell the surface. It varies.

Is it fascinating?

Often it is, he said. Not always. The other day, I felt such a sleepiness overtake me while talking to someone. Powerful! Like I was the most tired person alive. But when you feel such a sleepiness you need to ask yourself, Is it me? Am I sleepy? Did I not get enough sleep? Or: Is something being skipped over? Is someone dodging the truth and putting us both under? And when I thought of that I became very awake all of a sudden and we got to talking about something very, very different. Really, it is such interesting work.

How do you feel with me? she asked.

Oh, he sighed, with you? With you? I feel nothing is enough. I want to give you everything in this office, the walls, the floor. He reached into his drawer for scissors. I’m ready to chop off my hair, like Samson.

She smiled. Do it, she said.

He only clipped the ends, white, thick, like the bristles of a hairbrush. He handed the trimmings to her from a cupped palm. You hold the power now, he said. Did you check your garden?

I only have a side yard, she said. I don’t plant.

Check it, he said. See if there are holes.

They both stood, high-fived at her initiative.

What does your mother think of all this? he asked, walking her to the door, and she said she hadn’t mentioned it.

I don’t want her to be upset, she said. Not upset like mad. Upset like jealous.

Ah. He glanced at a small mirror at the doorway. Can you see the cut?

Only if you know where to look, she said.

He stood with her at the elevator. He was the neediness now, it was clear. She was sandwiched between their needinesses. What was her own? She’d never had a father but had not missed him in the same way, because there hadn’t been one to miss. But it was nice to have a grandfather now, she could not deny it. She found him elegant and broken in an appealing way. He might offer her things that could be useful to her life at large.

I’ll do the hair tonight, she said, and if anything shows up I’ll bring it and we can take an action with it. Okay?

Okay, he said.

That night she went to see her boyfriend. She was worried about them having sex because of the mud in the sheets and the wild fertility it claimed, but she stopped in anyway. She explained how she had to put the hair under her pillow at home, and she had a new relative she cared about, it was her grandfather, the betrayer of her mother, the traitor of her life, but now she really liked him, he was like her, she could see he loved her, and it wasn’t weird, but it was mean, she felt mean. Her boyfriend listened. He was making them pasta. Pasta and butter and parmesan. That was his best dish, but he did a special move with pasta water so it wasn’t as basic as it sounded.

I don’t judge you, he said. You should have a relationship with your grandfather if you want.

It’s like the dirt, the silt, the mud—they were giving me him. You know? I feel that. Because he’s a fucking DREAM doctor. How could I not go find him? His office is literally twelve blocks away.

That’s a cool job, he said, pouring the full pot into the waiting colander. Could you grab the bowls?

His roommate was out playing cards with some friends. They had the place to themselves. The boyfriend, it turned out, wasn’t in the mood for intercourse-style sex—he’d injured his groin playing soccer the other day. They could do other stuff, though.

Later, after dinner, after other stuff, she showed him the locks of hair, white and bristled. The boyfriend did not make fun of her. You want to try it here? he said, holding up his pillow, but she thought her bed was the place.

I like taking his stuff, she said.

She got home late, tired, but she didn’t forget to tuck the hair under her pillow. She tossed and turned, and a part of her mind was always aware of her knees and feet, awaiting a deposit, wondering where it would come from, how it would arrive. She finally fell asleep soundly in the early hours of the morning, and she dreamed, this time, of walking with her mother through a mall, slightly levitating, holding large shopping bags full of wigs. Wigs of all colors and lengths, red curls, long blonde tresses, short and capped and black. Hairs tendriling out of the tops of the bags. When, in the dream, they reached the food court, the mother turned to the daughter and said: I will order you for lunch.

She didn’t even check right away when she woke up, startled, alert. I will order you for lunch, she thought. What the fuck. She replayed it in her memory. It was not: I will order you lunch. She was the lunch, that was for sure.

She was getting up to shower for work and only the prickly sensation by her feet alerted her, and then, yes, grass, cut grass, green, not so unlike hair, a pile of it, almost looking like it had grown right out of the bedsheet. Smelling of spring, even though it was fall. The hair under the pillow, when she checked, was gone.

She called in to work. Said she was sick. Put the grass into a little baggie. Stopped and glanced at the side garden on the way out. The dirt didn’t look different to her: no holes, no ripped piece of lawn, but was there something growing in the mud glop? When she stepped over to look she glimpsed the edge of a white stem, almost like a doll tooth, poking out the top. That mud, still wet, even though the days had been dry. What was this side yard for anyway? How come no one ever used it?

She got to his office as fast as she could, but when she arrived, the door was closed. When she knocked, no one answered. Was it the weekend? No, it was a Wednesday. She checked her watch. Nine am. She’d been there at this time before.

For a strong moment, standing there, holding the little baggie of lawn grass, she felt a sensation of freefall in her own body. Had he left? What if it was too much for him, again? What if he was gone, forever, packed up, to China, or Australia, or a conference in New York? She had never before felt her mother so clearly inside her own body, the ache, the helplessness, the feeling she’d done it somehow, she’d chased him off. Then the elevator dinged and he exited with his briefcase and uncombed slightly shorn mane and he grinned at her, a beam of light, and everything that had been tossed into hell resettled in its proper spot, and he said he was so glad to see her, he started late on Wednesdays, and she said she too was glad, she was glad, but an uneasiness remained.

I got a muffin, he said. Bran and blueberry. Want half?

It was her mother in there with them now. She had been peripheral but now she was firmly ensconced in the middle. What a sadness her mother had felt. She had only held a second of it, fully grown, and it still had taken her breath away.

You okay? he said, opening his door, ushering her inside.

She sat down in the swivel chair. I don’t know, she said, swiveling. She held up the bag. You turned into grass.

Really? he said. His eyebrows raised with interest. Look at that! So textural, isn’t it, this spirit of yours! Quite poetic.

She handed him the bag. About the same amount, too, she said.

He turned it over in his hands. Smelled it, as she had.

Absolutely fascinating, he said. You have a lawn?

Just that strip of dirt, she said. With nothing growing except one tooth thing in the mud. Lawns are going out of style.

A tooth thing? he said.

She thought of her mother in the dream ready to order her at the food court, the pretzel stand, the burger stand, the Chinese food stand, her.

I thought you’d left, she said. When I was waiting. I thought maybe you’d flown the coop. I’d never really felt anything like that before.

He paused his eating. The desk was covered in muffin crumbs.

She sighed. Do you have a little time? she said. Can you come with me somewhere?

They walked the twelve blocks to her apartment. She would not take him inside; that felt too much. He would see the pictures on her walls. He would see her pots and pans, whatever that meant. But they went to the side strip of dirt. She showed him the glob of mud, the white tooth-like stem growing out of it.

Should we plant the grass?

There are no seeds, he said. It won’t grow.

No, she said.

They stood together.

No holes either, he said.

No.

It looked like a grave, the long rectangle strip of dirt with the tooth plant right around where a head might be.

Can I keep you? she said. Am I allowed to keep you?

Please, keep me, he said. You could sprinkle the grass. Like a blanket. When I die, will you bury me here?

Oh, I don’t own the building, she said.

Sneak me in, he said.

She smiled.

My ashes, my body, whatever I am, he said. Please. I’m serious. What an end that would be, to rest at the place that brought you to me, the great gift of my old age. Twelve blocks from my work!

I’ll move someday, she said. Maybe even soon. This is just a temporary station.

The little tooth plant swayed in the breeze.

Even better, he said. Bring me here, and leave me.

__________________________________

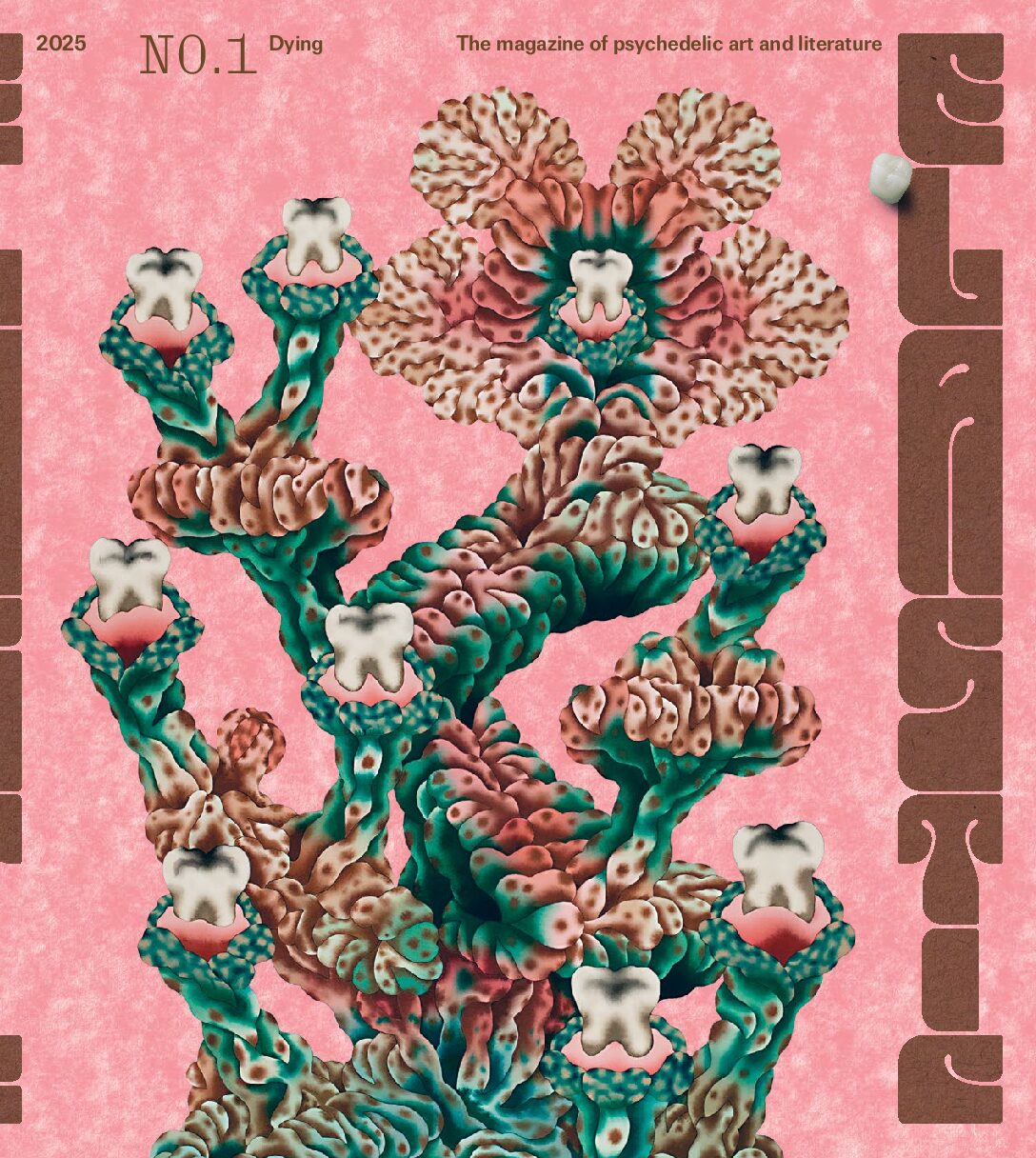

“Visitations” first appeared in Elastic magazine’s spring 2025 issue. Copyright © 2025 by Aimee Bender. Reprinted by permission of Elastic and the author.