The pandemic had not taken my family by surprise. As soon as word spread about the dying people in the streets near the port and the alarming number of blue corpses in the morgue, my father, Arsenio Del Valle, calculated that the plague would not take more than a few days to reach the capital, but he did not lose his calm. He had prepared for this eventuality with the efficiency he applied to his business. He was the only one of his brothers on track to recover the prestige and wealth that my grandfather had inherited but lost over the years because he’d had too many children and because he was an honest man. Of my grandfather’s fifteen children, eleven survived, a considerable number that proved the heartiness of the Del Valle bloodline, as my father liked to brag. But such a large family took a lot of effort and money to maintain, and the fortune had dwindled.

Before the national press ever called the illness by its name, my father already knew that it was the Spanish flu. He kept up to date on the news of the world through foreign newspapers, which arrived with considerable delay to the Union Club but provided better information than the local papers, and via a radio he had built himself by following the instructions in a manual to keep in touch with other enthusiasts. And so, punctuated by the static and shrieks of the shortwave, he learned of the havoc wreaked by the pandemic in other places. He had followed the advance of the virus from the beginning, and he knew how it had blown through Europe and the United States like a deadly breeze. He deduced that if civilized countries had experienced such tragic consequences we should expect worse in ours, where resources were more limited.

The Spanish influenza, “the flu” for short, reached us after almost two years’ delay. According to the scientific community, we’d be spared infection entirely due to our geographic isolation, the natural barrier afforded by the mountains to one side and the ocean to the other, as well as our remoteness. Popular opinion, however, attributed our salvation to Father Juan Quiroga, in whose honor precautionary processions were held. Quiroga is the only saint worth worshipping, because no one can outdo him when it comes to domestic miracles, even if the Vatican has failed to canonize him. Nevertheless, in 1920 the virus arrived in all its majestic glory with more force than anyone could have imagined, toppling the notions of scientists and theologians alike.

The onset of illness brought first a terrible chill from beyond the grave, which nothing could quell, followed by fevered shivering, a pounding headache, a blazing fire behind the eyes and in the throat, and deliriums, with terrifying hallucinations of death lurking steps away. The person’s skin turned a purplish blue color that soon darkened until the feet and hands were black; a cough impeded breathing as a bloody foam flooded the lungs, the victim moaned and writhed in agony, and the end arrived by asphyxiation. The most fortunate ones were dead in just a few hours.

My father suspected, on good grounds, that the flu had reaped a greater death toll among the soldiers in Europe, huddled in the trenches with no way to mitigate the spread, than the bullets and mustard gas had. It ravaged the United States and Mexico with equal ferocity and then turned toward South America. The newspapers said that in other countries the bodies were piled up like cordwood along the streets because there was not enough time or cemetery space to bury them all, that a third of humanity was infected, and that there were more than fifty million victims. The reports were as contradictory as the terrifying rumors that circulated. It had been eighteen months since the armistice had been signed, putting an end to the four horrific years of the Great War in Europe. But the full scope of the pandemic, which military censorship had covered up, was only just starting to be understood. No nation had wanted to report the true number of deaths. Only Spain, who had remained neutral in the conflict, shared news of the illness, which is why it ended up being called the Spanish influenza.

Before, the people of our country had always died from the usual causes, which is to say, crushing poverty, vices, violence, accidents, contaminated water, typhus, or the normal wear and tear of years. It was a natural process that culminated in a dignified burial. But with the arrival of the flu, which pounced on us like a voracious tiger, we were forced to dispense with consolation for the dying and the regular rituals of mourning.

The first cases were detected in the houses of ill repute near the port in late autumn, but no one except my father paid them much mind, since the victims were mostly women of dubious virtue, criminals, and smugglers. They said it was a venereal disease brought over from Indonesia by sailors passing through. Very quickly, however, it was impossible to ignore the widespread catastrophe or continue blaming promiscuity and happy living, because the illness did not discriminate between sinners and saints. The virus triumphed over Father Quiroga and moved freely through the population, viciously assailing children, the elderly, rich and poor alike. When an entire company of zarzuela singers and several members of Congress fell ill, the tabloids announced the Apocalypse and the government decided to close the borders and restrict the ports. But it was already too late.

Masses presided over by three priests with little bags of camphor tied around the neck did nothing to ward off infection. Winter was just around the corner and the first rains made the situation worse. Field hospitals sprang up on soccer pitches, makeshift morgues appeared in the meat lockers of the local slaughterhouse, and mass graves were dug for the bodies of the poor to be dumped and covered in lime. Since it was already understood that the illness entered the body through the breath and not from a mosquito bite or stomach worms, as had been widely believed, the use of face coverings was ordered. But since there weren’t even sufficient masks for health workers, who fought on the front lines, there certainly weren’t enough to go around for the general population.

The president of the nation, son of an Italian immigrant, with progressive ideas, had been elected a few months prior thanks to the vote of the emerging middle class and the worker’s unions. My father, like all his Del Valle relatives, friends, and acquaintances, distrusted the man because of the reforms he’d vowed to implement—highly inconvenient for the conservatives—and because he was an upstart without an old Spanish-Basque surname, but my father did approve of how he’d tackled the public health crisis. The first measure was a stay-at-home order to curb the spread, but since no one heeded it, the president decreed a state of emergency, a nightly curfew, and a ban on free circulation of the civil population without due cause, under penalty of fine, arrest, and, in many cases, beatings.

Schools were closed, as well as shops, parks, and other places where people typically congregated, but some public offices and banks remained open. The trucks and cargo trains continued to deliver supplies, and liquor stores had license to operate, since it was believed that alcohol with a large dose of aspirin would kill the virus. No one counted the number of people poisoned by that combination of alcohol and aspirin, as pointed out by my aunt Pía, who did not drink and didn’t believe in pharmaceutical remedies either. The police were overwhelmed and unable to impose order and prevent crime, just as my father had feared, and soldiers were called in to patrol the streets, despite their well-earned reputation for brutality. This rang an alarm bell for the opposition parties, intellectuals, and artists, who had not forgotten the massacre of defenseless workers, including women and children, carried out by the military a few years prior, as well as other instances in which they’d brandished their bayonets against civilians, treating our people like foreign enemies.

The shrine of Juan Quiroga was thronged with devotees seeking to cure themselves of the influenza, and in many cases they saw improvement. The skeptics, who can always be counted on to give their two cents, said that any person who could climb the thirty-two steps of the San Cerro Pedro Chapel was already on the mend. This did not discourage the faithful. Despite the fact that public gatherings were prohibited, a crowd led by two bishops marched to the shrine but were quickly scattered by soldiers doling out bullets and beatings. In under fifteen minutes they left two bodies dead in the street and sixty-three wounded, one of whom perished later that night. The bishops’ formal protest was ignored by the president, who refused to receive the prelates in his office and instead answered in writing through his secretary that “anyone, even the Pope, who disobeys a public ordinance will feel the firm hand of the law.” No more pilgrimages were attempted after that.

There wasn’t a single infected person in our family because, before the government had even issued measures to curb spread, my father had already made preparations, taking his cue from the methods of combatting the pandemic in other countries. He got on the radio and contacted the foreman of his sawmill, a highly trustworthy Croatian immigrant, and had two of their best loggers sent up from the south. He armed the men with ancient rifles, planted one at each entrance to our property, and assigned them the task of ensuring that no one entered or exited the premises, except himself and my oldest brother. It was a ridiculous order, because they couldn’t realistically shoot members of the family, but the presence of these men was mostly meant to dissuade looters. The loggers, transformed overnight into armed guards, never entered the house; they slept on pallets in the garage, ate food that the cook served them through the window, and drank the mule-killer aguardiente that my father provided in limitless supply, along with handfuls of aspirin, to keep the illness at bay.

__________________________________

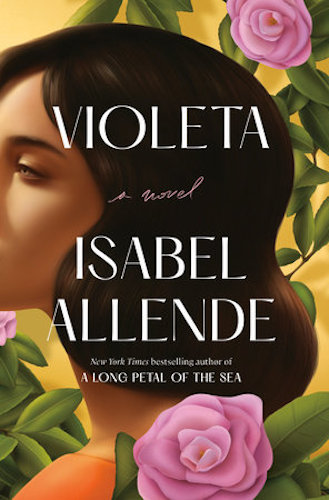

Excerpted from Violeta by Isabel Allende, translated by Frances Riddle. Used with permission of the publisher, Ballantine Books. Copyright © 2022.