Viewing Blackness Through the Lives of the Medici

Katy Simpson Smith on Identity, Racism, and Reclamation

There are two extant paintings of Giulia de’ Medici, a noblewoman who lived in 16th-century Italy and did noblewoman things, like marrying a cousin and stockpiling land. In one image she’s a young woman surrounded by symbols of Medici power, and in the other she’s a child, pout-faced and vulnerable. So vulnerable, in fact, that at some point she was entirely painted out—perhaps because she was an illegitimate child, or because she was a girl, or because she had African ancestry.

The Medici, one of the richest and most pope-producing families of Renaissance Italy, had a line descended from Simonetta da Collevecchio, an enslaved or indentured woman who was thought to be Moorish. Alessandro, Duke of Florence, was her son, curly-headed and dark-skinned; Giulia was his daughter, often described as being a mirror of her father. Alessandro was also called “Il Moro,” the Moor, though possibly not till after his death. His Blackness may have been inscribed onto his body later by rivals, or by historians who saw his reign as peculiarly tyrannical.

Twice since the 19th century scientists have exhumed his body to determine, among other things, his race, as if Blackness could be found in bones. Cultural theorist Mary Gallucci wonders why we care, when the Florentines probably didn’t. Because the Medici are synonymous with European power, and Blackness is unexpected in that sphere? What we now think of as race bears only a glancing relation to 16th-century hierarchies of color and caste, what Gallucci calls “a horizontal multicultural world.”

The first painting of Giulia is by Pontormo: a woman (Maria Salviati, Duke Cosimo de’ Medici’s mother) holding the hand of a child. Sometime between 1600 and 1900, the child was painted over; someone decided Maria Salviati looked better alone—haunting, all-over white. When the painting was cleaned in 1937, a girl emerged from the shadows. Some claimed it was Cosimo, a little boy; others said it was Bia, Maria’s legitimate (white) granddaughter. But a shaky consensus, led by art historian Gabrielle Langdon, has settled on Giulia. Does she look Black in this portrait? Black enough to erase?

The second painting is by Alessandro Allori, a protégé of Bronzino, and Giulia now is in her mid-twenties, already widowed. Her hair is still dark and curled, her skin a shade dimmer than the rosy pinks of the other Medici girls. She is distinct, one might say, but not marked. She’s also surrounding by meaning: the symbols and trappings of wealth that families paid painters to include, from the plaintive statue of Rachel to the cameo of Mercury to illustrations of Michelangelo’s sculptures of Day and Night. Wealth, power, piety.

The first painting is housed at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore; the second painting is in Florence’s Uffizi.

In 2015, I began working on a novel with Giulia de’ Medici as a heroine. That painting by Allori became a key encounter; her Blackness became important to her character. I wanted desperately to find these images of her, to see what she saw of herself.

In September 2017, I traveled by train to Florence, where I showed up to the Uffizi on a rainy Friday evening and moved slowly from room to room, waiting for her to appear. Several hours later, having twice passed the gallery of Medici portraits, I approached a security guard—one of those who seem especially chosen because of their invulnerability to art—and asked her in stumbling Italian where Giulia was. She pointed to Room #67, which was roped off for a periodic cleaning. On the far wall, across the wide floor from the flimsy rope and stanchions, a dark rectangle held a flash of gold: Giulia.

I turned to the guard, dug myself deeper into an Italian hole. I am writing a novel about her, I said; I am a historian and a writer and she, that woman, is in my book, and I have come a far way to see her. I am only here for one night, and I am writing a novel, and I only need to see her quick. But the Uffizi was unflinching. I asked another guard, I asked a third, I was directed to a manager. A novel! I kept saying. When there was no one left to ask, I turned my face to the corner of the Medici room and cried. I left Florence the next day on the train.

To find a glimmer of Blackness in the most powerful family in Renaissance Italy is to connect identity and opportunity, to find a seed of the Black self in yet another powerful place.

In March 2018, I drove from my home in New Orleans to Charlottesville to visit family—and to take the train to Baltimore to see young Giulia. I emailed the museum’s curator in advance to make sure the portrait would be hanging and visible—of course, she said, it’s always there. My first day in Charlottesville I came down with the flu; I spent the next week holed up in a motel, my brother dropping off daily rations of soup and tea, and when I was well enough to stagger to the door without falling, I had to drive the fourteen hours home again. The curse of the Medici, I thought.

Historian Mario de Valdes y Cocom, who helped identify Giulia in the Baltimore portrait, sees the potential of that Blackness as revolutionary. One of the first representations of a Black girl in Renaissance art, it may have been neither an assertion nor a defense, but a simple depiction of a face among other faces in Gallucci’s “horizontal multicultural world.” But by 1902, when Henry Walters bought it for his Baltimore collection, Giulia had been painted over. After X-rays found her in the ’30s and she was dragged through layers of oil back to life, she was reborn into an era when Blackness carried new meaning. The horizontal world had been lost.

In December 2018, I went back to Baltimore. I fumbled my way downtown from the Amtrak station, burst through the doors of the museum, and breathlessly told the young man at the information desk who asked if I needed help that yes, I wanted to see one thing and one thing only, and he pointed out the room on the map, and I ran up the stairs to a long gallery wallpapered in green brocade. Directly ahead of me was a copy of the Mona Lisa. I turned as slow as an inchworm, feeling it in my bones, the hairs on my arms beginning to crackle with the electricity of closeness, and there, directly behind me, was a small mixed-race child, curly-headed, questioning, her fingers wrapped in the fingers of her grandmother, her skin glowing like a metal. Giulia de’ Medici.

Is it useful to project modern ideas about race onto the past? From a historical perspective, no. We learn nothing about the past that way. And yet anachronistic definitions of race matter because contemporary race matters. To find a glimmer of Blackness in the most powerful family in Renaissance Italy is to connect identity and opportunity, to find a seed of the Black self in yet another powerful place. We want to read Blackness backward in time precisely because of the journey it’s taken since.

We look for visual evidence of race not because it mattered to them but because it matters now.

I sat on the bench and watched Giulia for an hour; like all good art, the painting seemed to move. I had seen her grandmother’s quarters in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, a warren of rooms below the Duke’s, with her own privy carved into the wall. I had seen the palace where the Medici children had moved after Cosimo’s rise to power, when the city center was no longer safe. I had seen the burial gown of the woman who raised Giulia after her parents had died. I had tracked the places where Giulia’s body might have gone, and followed her invisible trail through time here, to her childhood nonwhite self, in Baltimore, a city that’s sixty-three percent Black.

Our caring about the Medici’s color has accumulated over the centuries, shifting from racism to reclamation, from normalcy to exclusion to pride. We look for visual evidence of race not because it mattered to them but because it matters now. As a historian, I should see this as dangerous presentism, selfishness leading to inaccuracy. But as a novelist, I also hunt for the way emotion elides time.

We sit in front of portraits in museums because we want to see what someone else looked like, long ago, somewhere else, but also because we secretly hope that we will see some shard of ourselves there, that the past is not really past, but is possibility.

__________________________________

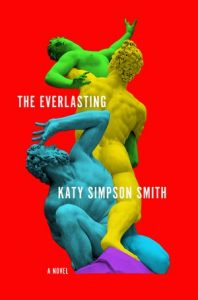

The Everlasting by Katy Simpson Smith is available now via Harper.

Katy Simpson Smith

Katy Simpson Smith was born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi. She is the author of the novels The Story of Land and Sea, a Vogue best book of the year; Free Men; and The Everlasting, a New York Times best historical fiction book of the year. She is also the author of We Have Raised All of You: Motherhood in the South, 1750–1835. Her writing has appeared in The Paris Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Oxford American, Granta, and Literary Hub, among other publications. She received a PhD in history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars. She lives in New Orleans.