Viet Thanh Nguyen on the Cover of His New Memoir

“It often feels like a cover designer I have not met has captured some dimension of the book I have not been aware.”

The book is finished, in one sense, and not finished in another sense. Story and words are there, copy editing is done, pages laid out, an ISBN number assigned. What remains is the cover, something over which the author has little control, and yet what potential readers will see first.

In many cases, the cover is the only thing potential readers will see of the book. Their eyes will slide over the cover, the title, the author’s name, the endorsements, the excerpts of reviews, the plot summary, and for whatever reason, they will not be persuaded to buy or borrow the book.

I have done exactly this to an untold number of books. I have browsed the book shelves and display tables of bookstores and libraries, and in most cases, I have been guilty of not picking up the book. The cover has not worked enough of its subliminal magic, its mix of art and aspiration and advertising, its flaunting of the title and the author’s name. And then there are many cases where the covers and everything they sported did accomplish their magic, and after admiring the cover, I bought the book, and brought it home, and did not read the book.

The cover can only do so much. It cannot compel the reader to actually read the book, or hide the imperfections of a book or the ways in which it might not be a good match for a reader. But the cover can capture some part of a book, or fail to do so, and knowing this, I wait for the arrival of my own covers with some anxiety and excitement. The covers, or the drafts of them, are always a surprise.

I have never had a direct conversation with the artists who designed my book covers, and for good reason. Authors tend to be anxious creatures, at least about the writing of their books and the reception of them, and it is the job of editors to manage the anxieties of their authors, not expose others to them.

Oftentimes it feels as if this cover designer I have not met has captured some dimension of the book I have not been aware of at an explicit level.

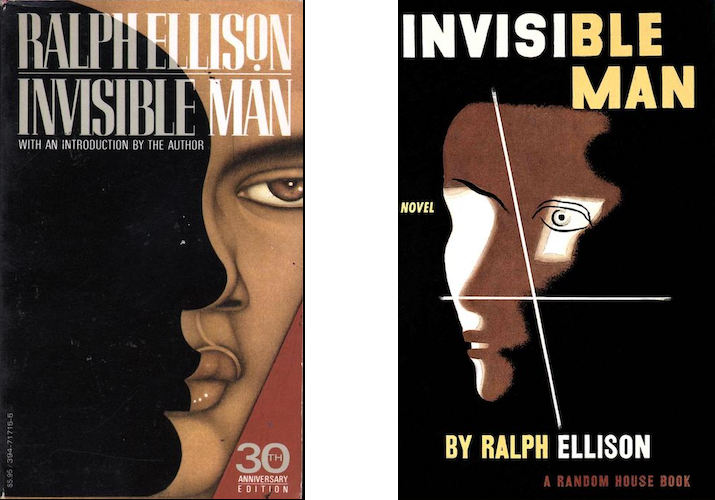

In ideal cases, my editors in the US and UK have solicited my opinions about the cover. Sometimes, before publication, I am presented with one draft of the cover, sometimes with several. I am not a visual person, and so I have little sense of what my ideal cover should be, although I have favorite covers from other writers, including some of the covers for Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, a novel that deeply influenced The Sympathizer. Seeing a beautiful cover is a reminder that covers themselves are works of art, and yet I have little control over them.

My vision is in the service of another artist, sometimes many artists, for I have been fortunate to have many foreign editions of my books. The covers have proliferated, almost always without any consultation from me. Once or twice I have been horrified or disappointed by what I have seen, but oftentimes it feels as if this cover designer I have not met has captured some dimension of the book I have not been aware of at an explicit level, or has created a visual analogue to the book that I could not have imagined for myself. Mostly, I feel grateful that another creative person has gazed into the well of their imagination and found, shimmering on the surface of the water, the idea of my book.

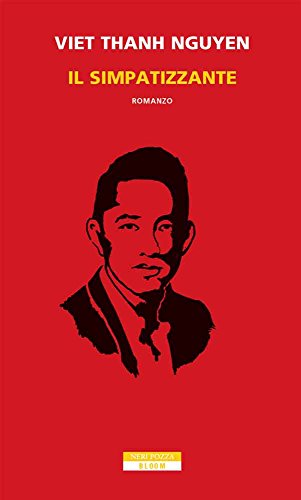

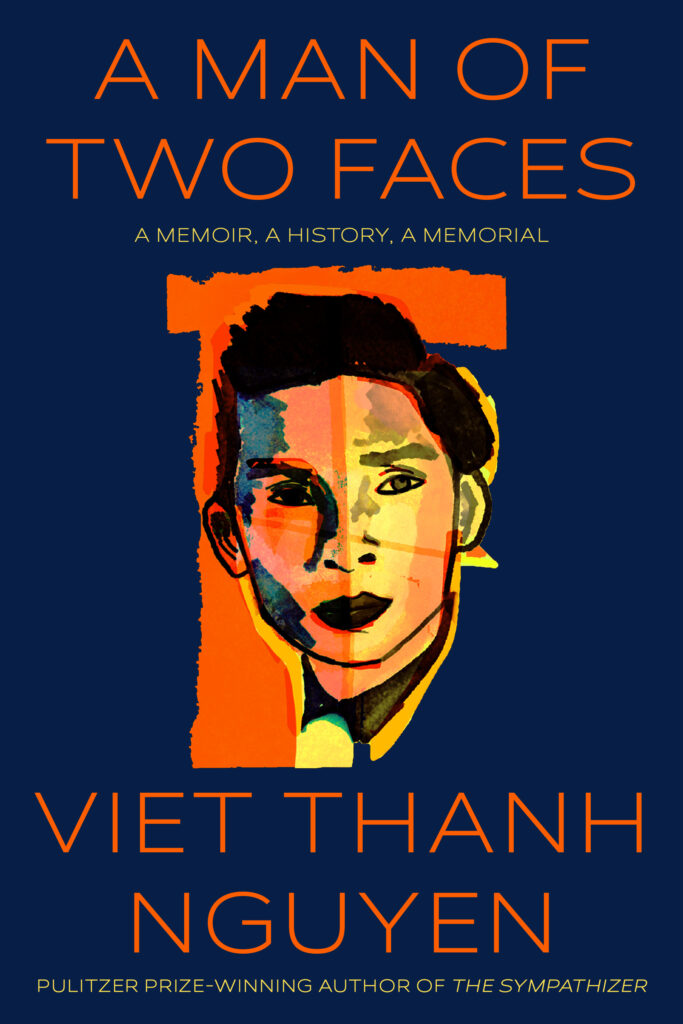

This newest book is titled A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial. The subtitle is mine, but the title comes from the writer Laila Lalami, who read the book in manuscript and grasped the essence of it. The cover design is by Kelly Winton, under the supervision of Gretchen Mergenthaler, the art director for Grove Atlantic, my American publisher. Not surprisingly, there is a face on the cover of the book. I felt a shock of recognition, seeing that face on the cover for the first time. The reader might think that the face is mine, which is definitely the case on Il simpatizzante, the Italian edition of The Sympathizer.

Perhaps Corrado Bosi, the cover designer, discerned something about the novel, namely that there was a considerable degree of me in the novel’s narrator, who introduces himself to the reader as “a man of two faces.” Strangely enough, my creation of this man of two faces—the Sympathizer—was what would allow me, eventually, to write A Man of Two Faces. Reluctant to write about myself, I imagined the Sympathizer writing about me as if he were me, which I suppose he might be.

And yet the face the reader sees on the cover of A Man of Two Faces is my father’s, taken from a studio photograph of him when he was in his twenties or early thirties. The photograph appeared in the penultimate draft of the book, but has since been taken out by me. So it was wonderful to see that Winton had used this particular photograph, because, as she puts it, “I love his elegance and expression.” As do I.

Taking a cue from me, Winton was inspired by the covers of Invisible Man, and perhaps I am an invisible man lurking behind my father’s face, waiting to be born. And, eventually, to grow into my father’s face. Not exactly, but somewhat. Not only physically, but psychically. I wonder if I sometimes wear his face. I certainly feel that way when I speak to my children and hear myself speaking like a father. Like my father. Like someone I never thought I would become.

If readers are so tempted as to pick up the book and open it, they will see a photograph at the beginning which is of my mother and me, around three years of age, walking under an archway of rubber trees on a distant plantation, heading towards the photographer. I have no memory of this moment. I assume my father took the photograph. Who else would? I have never seen the physical photograph. My older (adopted) sister, left behind in Việt Nam during the chaos that was the end of the war, which turned the rest of my family into refugees, sent the digital version to us some 40 years after it was taken.

If readers flip the pages quickly to the end, they will see another photograph, this time of my mother and me walking away from the photographer. Towards a future that we, blissfully unaware, could not yet see. My father, always keen for the latest in technology, has just pressed his shutter, the camera against his eye. Against his face. The readers see my mother and me, but they are seeing through my father’s gaze. The gaze that looks out at them from the cover of the book they hold in their hands. The eyes of the potential readers meet my father’s eyes. For a moment. And if that glance is all there is, that, for me, is enough. My father has been seen.

A Man of Two Faces will publish from Grove Press in October 3, 2023.

Viet Thanh Nguyen

Viet Thanh Nguyen was born in Vietnam and raised in America. He is the author of The Committed, which continues the story of The Sympathizer, awarded the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. He is also the author of the short story collection The Refugees; the nonfiction book Nothing Ever Dies, a finalist for the National Book Award; To Save and to Destroy: Writing as an Other; and is the editor of an anthology of refugee writing, The Displaced. He is the Aerol Arnold Professor of English and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California and a recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim and MacArthur foundations. He lives in Los Angeles.