Victoria Shorr on the Art of the Novella

”They take you—for one evening if you don't put it down, longer if you draw it out—to a place that you can see in sharp detail.”

Penelope Fitzgerald wrote novellas. So did Caroline Blackwood, J.L. Carr, Edith Wharton, and so do I. I never mean to. I don’t start out thinking “novella”—it’s not like writing a short story. Because that’s an entirely different approach.

When you decide to write a short story, you go in armed and ready for battle with time and space. You’ve got 13 pages, and you already know your beginning and your end. Your job is to get from the one to the other, meanwhile lopping the heads off the thousand flowers that beckon you away from your clear, concise outline. The muse has come early, but has struck a hard bargain. Inspiration, but you can’t step off the path.

This was perfect for me when I was younger, with three small time-consuming children, but the strong desire to write about Brazil, where I was living then. The short story came to my rescue. I realized that through a series of short stories, written in the hours I could steal at my desk, I could convey some essence of the whole—a picture, in my case, of ex-patriate Brazil in the 80s, told in 13-page increments. Hard work, by the way, but not unsuited to a woman with nothing close to a room of her own.

But then, as the years rolled on, I found myself with more time and space, able now to set my sights on tales that could flow along at a more leisurely pace. The children were away at school. The 1,000-page doorstop could now be mine.

But it hasn’t been, and probably won’t be, because even though it’s been a while since I was up against the thirteen pages, still I rarely find I have much to say that goes beyond the length of the novella.

Partly it’s the internet. We’ve learned to speak more directly to each other, without all the curlicues and asides and explications our forefathers found de rigeur, and that only tend to exasperate, these days—have you tried to re-read Dickens?

But I also suspect something else at play in my case, something to do with being a woman, though older—with grandchildren now, but still the laundry piling up, and an aged mother. Voting rights to support, and a girls’ school on the Pine Ridge Reservation—in other words, a life on the other side of my own pages. This must have, over the years, led to an economy of form, since in my own case, the result of my sitting down to write doesn’t usually go much beyond novella length.

They take you—for one evening if you don’t put it down, longer if you draw it out—to a place that you can see in sharp detail, and feel and know, right then, in that intense moment.

In my defense—and in defense of the novella—the funny thing is that I never feel that I have left anything out. I have found that when I type o fim, “the end,” and look up from my work, I feel that I have satisfactorily, if not exhaustively, chronicled whatever it is that has captivated me in the first place, despite there being no more than, say, seventy pages. Maybe a hundred, once I double space it. Put it into Didot, the typeface that Mary Shelley used. Short works, true, but all I have to say on the subject. I press “Save” and walk away, feeling, I suspect, quite as fulfilled as Tolstoy on page 1231 of War and Peace.

Which actually brings us to the elephant in this particular room: What can you get from a novella of ninety-two pages as opposed to, say, War and Peace? Well, for one thing, if the writer has done her job, you get an intensity that would have been diluted had it been dragged out over several hundred pages. You are sitting with someone who feels like you do about your time—it’s valuable. So is hers. She has a grocery list sitting beside her story outline, and has learned, by necessity, how to essentialize.

There will not, in her novella, be the kind of 300-page side stories where the author’s dearly beloved, bearish alter ego marries the beautiful young girl. Nor can there be much in the way of extraneous events happening offscreen. There will be a young man, injured in World War I, going to a village to fix a damaged church and almost finding love [Carr’s A Month in the Country]. There will be a really brilliant snapshot of a woman and her children living a sketchy life on a precarious barge on the Thames [Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald]. There will be a portrait of a declining genteel WASP family in the New York of the 70s, as they come together at a dinner one summer night [my own Great Uncle Edward].

War and Peace these novellas are not. They don’t offer the broad view, nor do they function through revealing the panoply of an age. Instead, they home in and bring you up close to their subject, right away. They take you—for one evening if you don’t put it down, longer if you draw it out—to a place that you can see in sharp detail, and feel and know, right then, in that intense moment.

They are mindful, like a Thich Nhat Hanh meditation. They want to be, have to be.

Since the writer mostly doesn’t have any more time than you do. Unlike Tolstoy, she has dinner to cook.

__________________________________________________________

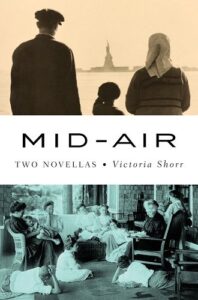

Victoria Shorr’s Mid-Air is available now via W. W. Norton & Company.

Victoria Shorr

Victoria Shorr is author of the novels The Plum Trees, Midnight, and Backlands. She cofounded the Archer School for Girls in Los Angeles and the Pine Ridge Girls' School in South Dakota, the first independent, culturally based college-prep school for girls on a Native reservation in America. She lives in New York, New York.