Victoria Chang on the Self

and Its Many Deaths

The Author of OBIT in Conversation with Peter Mishler

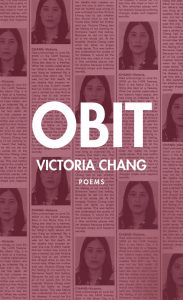

For the next installation in our interview series with contemporary poets, Peter Mishler corresponded with Victoria Chang. Victoria Chang’s books include OBIT (April 2020), Barbie Chang, The Boss, Salvinia Molesta, and Circle. Her children’s picture book, Is Mommy?, was illustrated by Marla Frazee and published by Beach Lane Books/Simon & Schuster. It was named a New York Times Notable Book. Her middle grade novel Love, Love will be published by Sterling Publishing in 2020. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award, the Poetry Society of America’s Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award, a Pushcart Prize, a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, and a Lannan Residency Fellowship. She lives in Los Angeles and is the program chair of Antioch’s Low-Residency MFA Program.

*

Peter Mishler: What is the strangest thing you know to be true about the art of poetry?

Victoria Chang: I find all of poetry strange, truthfully, in the best of ways. It’s so mysterious and I love the process of writing because it is a process of discovery. While working on OBIT, all the usual strange things occurred from the initial trigger to write in an obituary form to the actual writing process itself. The whole process is very magical and it’s so addictive that I find myself seeking that surprise like a kind of drug every time I sit down to write. There’s nothing in the world that makes me quite as happy as when I’m writing. Obviously, it’s hard, but I enjoy that difficulty. I also find it strange that after all these decades of writing, it still feels fresh every time. I find it so odd how boundless the human imagination is. I’m writing you from Marfa, Texas and I am so inspired and excited to write just being in a different physical location.

PM: Would you like to talk a little bit about what you are working on in Marfa?

VC: At the moment, I am procrastinating. I am working on a collection of these sort of hybrid, uncategorizable memoir essays about poetry. It’s really hard to explain because I’m forming it as I go or I should say, it is forming itself as I go. I haven’t written a poem in years, maybe three? I’ve been wanting to write poems but have been struggling. I finally decided that I don’t need to write poems for anyone but just for myself right now. A friend forced me to write poems back and forth as a way of correspondence when he was at MacDowell this week, so surprisingly I have written a slew of earnest bad poems. They are about nothing. They do nothing. They just are.

PM: Would you be willing to talk about a difficult experience in returning to writing after completing a collection or series of poems?

VC: I think all writing is difficult. I get bored very easily and am always looking for the next stimulation. It’s probably my best and worst quality. So I don’t think I struggle to find material to write about. I think life finds us in that way. What I find difficult every time is not boring myself. I read a lot so if I find myself writing in ways that have been written before, I get frustrated. I do think for me, reading is the best way to stimulate new ideas. Walking too. I used to run a lot until I herniated a bunch of discs and so I do a lot of walking now and I always think of new things when I’m walking. Living with chronic pain, as well as the illnesses of others (my parents) for so long, and generally being too busy, has made me really appreciate any time I do get to write so I bring a lot of excitement to the table when I sit down. Urgency is important.

PM: Is there an instance or memory or story from your childhood that you feel, at this point in your life, now stands as a metaphor for your eventual life as a writer, an artist?

VC: I don’t know if there’s one, but I was bullied growing up as a Chinese American in Michigan (I’ve just recently named it as bullying—in the past, I would pretend it never happened, ashamed of that part of my life), particularly in the later years of elementary school. I think that these experiences perhaps turned my usually gregarious extraverted self inward. I think that tension between the inward and outward is important in my work and in a very odd sense, I feel immensely grateful to those people that bullied me, not to say I would necessarily thank them today, but I don’t know if I would be a writer if I were not bullied (much of my bullying centered around both race and my physical appearance).

PM: One of my favorite observations in OBIT is your writing about the feeling of protection and care when the teacher would turn off the lights. Were you a poet in school?

VC: That was in high school. I was always very visible (being a person of color in a predominantly Jewish and white town), yet totally invisible. This tension created a lot of angst. I don’t know if I have ever not been a poet if that makes sense. I have always felt things very deeply, and also very broadly. There are a lot of ways to channel that energy. I am very excitable by nature. One could paint, run, play music, fix things. I’ve always written. I have a lot of secrets. I think people with a lot of secrets are good candidates for writing. I credit any introduction to poetry to my teachers in elementary school for introducing it to us. Once I found it, it wouldn’t leave me.

PM: What observations would you be willing to offer about the relationship between this new collection’s consideration of language, of representation in relation to its highly personal, autobiographical aspects?

VC: This relates to what I was just writing about above—I think if I were to look at my writing from the outside, the tension between the interior and the exterior is in the writing. Because I was trained to assimilate at such a young age, which has its pros and cons, I think I can be anything anyone wants me to be, meaning I am keenly aware of how other people feel or what other people want. I’m also very curious (too curious) about other people. I sense that in my own poems. The minute I sense that I’m too interior, I bounce back out into the world. I see this as both a kind of verticality and also a horizontal movement in perspective. I am in the end, very private and don’t like to talk about myself, so I think this is reflected in the writing too.

When my mother died, I died. But I am still here. How can that be?PM: Speaking of interiority, Tranströmer has earned your only obit for a writer in the collection (besides yourself—). What has his work taught you?

VC: The essays I’m working on now look toward poets like Tranströmer. Poems teach me everything. I look toward them when in need (which is all the time, it seems). Tranströmer casts spells as the writer Teju Cole once said in a review. There’s a kind of mysticism in his writing that I’m drawn to. He seems to address larger existential concerns that go up and down in the ladders of my own mind. Yet, he is all feeling. His poems feel like mist to me. I am in them when I read them. Fully embodied in mind and soul. Yet completely lost and in many ways released from the need to understand.

PM: Could you talk about the obits of yourself?

VC: When my mother died, I died. But I am still here. How can that be? I think writing those self-obits was a way of grappling with my own death. With my mother’s death, I had to change because I didn’t have that much time to grieve. I had to take care of my father, now on my own. He has help, of course, as it’s an impossibility to take care of him as one person, and I feel lucky in that way. But I had to step up and learn how to manage his care. I grew up faster than perhaps I wanted to.

The old self dies all the time, and it’s quite miraculous. Yet, I asked the man who runs these residencies in Marfa on the way in, what it’s like to be 77. He said, “I feel exactly the same.” How can this be? The tension between what remains and what is discarded in the self was really interesting to me. I always find it odd thinking about how we spend our whole lives learning and all that experience and knowledge accumulates, and then we die. Who designed this thing?

PM: Could you talk specifically about the final poem, the final Tanka, in the collection and where it appeared for you in the process of writing the book?

VC: The Tankas came after writing the majority of the OBITs. I was writing some formal poems just for fun, experimenting and not knowing how they would or if they wouldn’t fit anywhere and they didn’t (I was writing sestinas, villanelles, ghazals, etc.). I thought it might be fun to write Tankas, so I started writing them and never stopped. I’ve told this story a few times, but these were all in the back of the manuscript and a friend took one look (he’s one of the quickest, sharpest readers I know) and said, “Why don’t you spread these out? Put them throughout the manuscript?” I did and moved them around so that there was some kind of arc. He was right, of course. Sometimes we can’t see things that are obvious to other people.

PM: Would you be willing to make an observation about the constraints of the ‘obit’ form in terms of revision?

VC: These are essentially skinny prose poems and I’ve tried the prose poem form many times before but for whatever reason, it hasn’t worked well as a vessel for other poems. In this instance, the formal constraint seemed necessary. The form was less of a constraint though and was actually freeing—not having to focus on line breaks was very freeing. During revision, I just typed them into the document and voila, no line breaks necessary!

PM: I wondered about the book’s shift toward contemporary America—namely, American violence—that contextualizes the final poems in the book. What observations can you make about this gesture that arrives at the end of the collection?

VC: I wrote a few of those more “contemporary America” poems very late in the process, long after the two-week rush where the majority of the poems were written. The poem about gun violence was a prompt that Derek Sheffield, poetry editor of Terrain.org, asked me to write for their wonderful Dear America series. I hate writing towards prompts, despite loving to dispense them, so I thought I would try it and so that’s the penultimate poem in the book. Gun violence appears in the Tankas, and as I was working on this book, America was changing for the worse as I wrote so you can see it in the book too.

PM: What observations do you have in terms of writing directly to your children or including them in your work?

VC: I have a whole book of essays that continued from these Tankas to my children (or all children) so I never stopped! My children are such a big part of my life. A friend yesterday asked why I never talk about my family. He always bothers me about that. You see, they are 95 percent of my life. Why would I want to spend the last 5 percent of my life talking about them? The last 5 percent is also divided between work and other things so what’s left for me? 1 percent Well, I would like spending the last 1 percent of my time on myself, my writing, reading, talking about books, writing, etc. So they do appear in my writing sometimes.

Children are puzzles to me. I don’t understand them at all. I think writing to them or about them is another way of understanding not only them but also the world and our future. The world is a giant puzzle too. I don’t understand any of this. Why we are here, what we are supposed to do when we are here, how we grapple with the idea of leaving the earth. None of it makes any sense to me. I don’t care if they ever read what I write or not. They are not like me in many ways because they are growing up in a different city in a different time. They don’t experience the same kind of hardships that I did growing up in Michigan. But they have other hardships. I don’t know what to make of them at all. I have no idea what my role in their lives is supposed to be. It’s all very confusing all the time. If you figure it out, let me know.

__________________________________

Victoria Chang’s new book OBIT is coming out in April 2020 from Copper Canyon Press.