It wasn’t until after I dug out her body that I learned to love my sister, Marisol. You’d think it strange, to see destruction as a way to learn her, to grow with her and our people, but that’s how it went. It started with the mudslide that came through and busted my bedroom window. As huracán María raged outside, Marisol slept with all our dreams.

No one can tell you how much pressure is outside during a huracán. In the rain clouds unstitched, the wind breezing, and the storm, a large squeeze in your entrails and a hum so loud, you begin to forget. Those howls sing in tiresome anger. You feel your ears pop. “Las turbinas de un avión,” is what Mami chanted throughout the night. And I felt our house tremble like I believed God was fuming. We all did. Mami held on to us after the lights went. Mami felt the ground shake from under our feet and walked with Marisol and me, hand in hand, to the bathroom. There we curled under the wooden vanity and she prayed, “Dios will be here. He will.”

“But what if he’s not?” Marisol asked.

“He will!” I snapped back.

That was all I could say or needed to say. She tugged on my dress at first, then moved her fingers away from mine and left us there.

“Marisol!”

“Ya, Mami. I’m going to sleep.”

“So, sleep here, nena.”

But she didn’t listen. She went to my bedroom and shut the door and that was it.

*

Utuado was beautiful. A town that reached heaven, at least downtown where the church is. We lived way up; me, Marisol, Mami, and the neighbors. It was a beautiful place, the town center perched on a hill with a plaza central and all the shops run by friends. They sold yarn for knitters and there were cafeterias where you could get bacalao and tostones every day and as much as you like. Mari and me played there often when Mami ran errands. She spent a lot of days with el licenciado Cabán. She said she needed a lawyer a lot back in those days when Papi was still around. I didn’t like Cabán much. He always looked at Marisol funny, with hunger in his eyes even though she didn’t have anything to eat. This was before Papi finally disappeared. After Papi, I was happy because we didn’t need men like him in our lives. That’s what Mari used to say too. She was all sorts of maniática, with that quick and sharp temper which often collided with Mami. But that never bothered me since she loved me in her own way. She was pretty and unafraid. She liked to race me down the thin roads of our barrio, always sprinting down the jagged hillside where the bamboos twisted toward the river crest and the only visible shade of green was a constant fire. Mari wasn’t perfect. She needed things her way. Don Papo, our neighbor, used to joke that her manic episodes were her way of becoming a woman. He’d eye her from his butaca as he rocked back and forth, his hands clasping down at his crotch. An absent stare and deep brown eyes that wanted to penetrate us. His aged white skin like a cow’s hide would slick in sweat. He called me la fea because I was so big for a twelve year-old. My arms thick as palm trees. I was strong. I could lift Marisol up so high she reached the clouds. She told me that it didn’t matter what children said about me, Don Papo was the vicious type. Whenever we walked by his front porch back from school, Marisol always tried to rush me past his gaze, said to never go outside alone, never turn your back to that Viejo sucio. I try to remember as much as I can, but I keep hearing wind and seeing night.

The sea is out there somewhere in the darkness, behind all that used to be green, those tree spines and jagged caves. It takes a lot to get here, the roads narrow as you drive up from Arecibo and I imagine now it is harder to reach us. Energy comes and goes on normal days, so you can guess what mean weather can do. I call it that, even though everyone calls it gasoline and power. But I like Energy because it means more and it’s all the same. The people that brought the Energy my entire life warned that if something were to happen to the roads, the Energy would be difficult to repair because we were so far and high on the mountain. That made me chuckle because Energy is something that’s never consistent. It’s fragile. Some of us bought these portable electricity sources, but I hated them because when they were on, they sounded like lawnmowers, and if the Energy was gone for more than a day, the night was filled with a buzz so loud it was hard to think or sleep. I’m sure the coquíes hated them too because they weren’t able to sing to each other.

We all thought we were ready for María. Mami made sure to prep all the food and batteries and clothes. She had her machete sharpened. She was sure the trees around us would snap and fall everywhere, and she’d be the one to clean it all up. As the big night approached and María started making her mess, Mami sent me to the backyard as soon as the lights went to get the lime green kerosene lamp and machete. The lamp sat in the wooden shack that Mari and me helped build. We looked all over the sides of the mountain for wood the day we decided to build it and Mari always made me carry all the wood. She said I was the strong one even though she’s the eldest.

The machete was pierced into a wooden stump. I liked going out into the night because the air felt clean and the stars cast a large net above. I watched as the stars moved and the trees shuddered with the wind and I saw long stacks of smoke rising over the mountain’s silhouette as if a giant was ascending into the sky.

I grabbed Mami’s things and rushed back and yelled to them that there was something dark climbing our way.

“Mami, two long clouds are out there, and they keep moving toward us.”

Mami walked over to the kitchen window and pushed the curtain. “That’s smoke, Cami. Don’t worry about it. They must be burning something en la plaza.”

“But it’s moving toward us,” I said.

“Estúpida, that’s the wind.” Marisol said and rolled her eyes.

“Mami . . .” I said. I wanted to cry.

“Leave her alone, Marisol.” She turned to me and put her big hands over my head. “Cami, it won’t come this way. Don’t worry about it, mija. Now, you two come. Let’s go to my room.”

Mami wanted to sing us both a lullaby, which I always liked but Marisol hated. As María came and turned everything dark, Mami made us crawl into bed with her that night to sing. She started by first humming the words to “Lamento borincano” before shifting to La Lupe. La Lupe was Mami’s favorite. I liked La Lupe because her words sounded determined as though she were always angry at someone. They sounded like she needed to sing her songs, or she wouldn’t be able to live happily. Mami growled the same way, grunting when she reached for the highest notes. The whole house shook and the flames on the devotionals flickered. That was the power of her voice and she tried to tell us that La Lupe was the person to listen to if we were sad because she gave you powers through her songs. Marisol hated La Lupe, but I liked her.

So Mami started grunting and growling and her dark skin was fire and shadow in the darkness. I curled up next to Mami as she orchestrated the notes with her hands. The wind started picking up outside. Marisol sat on the edge of Mami’s bed and picked at her toes with a nail clipper. Her curly black hair fell down her back and she looked beautiful, as if she were a still bronze statue. But as Mami kept singing, Marisol grew impatient.

“Ya, Ma! It’s loud outside and now loud in here. I’m tired of those same songs again and again.”

Mami didn’t listen and kept singing. She winked at me as she continued to move her hands and it made me smile because I knew that Mami was there protecting us with a spell.

“Okay, Ma,” Marisol said getting up from the bed and walking toward the door. And Mami stopped midsong.

“Marisol! Come back here. I’m not done.”

“It’s really hard trying not to freak out and you’re over here acting like this is a game.”

“A game? Who said anything about a game, Marisol?”

“Forget it, Ma. I’m going to la sala.”

“Marisol, ¡quédate aquí! It’s safer here.”

“It’s like death and church in here. I’m going. I need quiet.”

“Marisol! I’m not telling you again.”

“Ya, Ma!”

Marisol opened the door and a shudder came into the room and the hairs on my back rose and it felt cold. Mami moved out of bed and grabbed Marisol by her thin arms and forced her back inside. She then slammed the door and sat on the bed next to one of her devotionals.

“Ma!”

“Ya, Marisol! Ya! It’s safer if we stay together.”

The wind started thumping on the windows and the trees outside were alive, screeching and howling louder and louder. I started to miss Mami’s singing.

Mami’s room was damp and cold and I knew Mari hated being there because she felt everything in there was judging her. Mami’s religious things, her many bibles, some bound in leather inscribed with our names, el padre nuestro framed nicely in gold over her night table, crucifixes on the walls, and devotionals.

She’d light them every night before bed. Some were lined on the nightstand and others on the wooden dresser. She had a few more in the bathroom behind the toilet seat. I smiled at those because it was like Mami needed help doing her business.

Those devotionals surrounded Mami and I think they made her feel safe and closer to God. Mami was that way. She even tried teaching me how to make rosaries once, but I never got the rhythm because my fingers are sausages. Mari would’ve been good at it if she had wanted to learn. She had those nice delicate hands, thin and long. I really liked her hands.

__________________________________

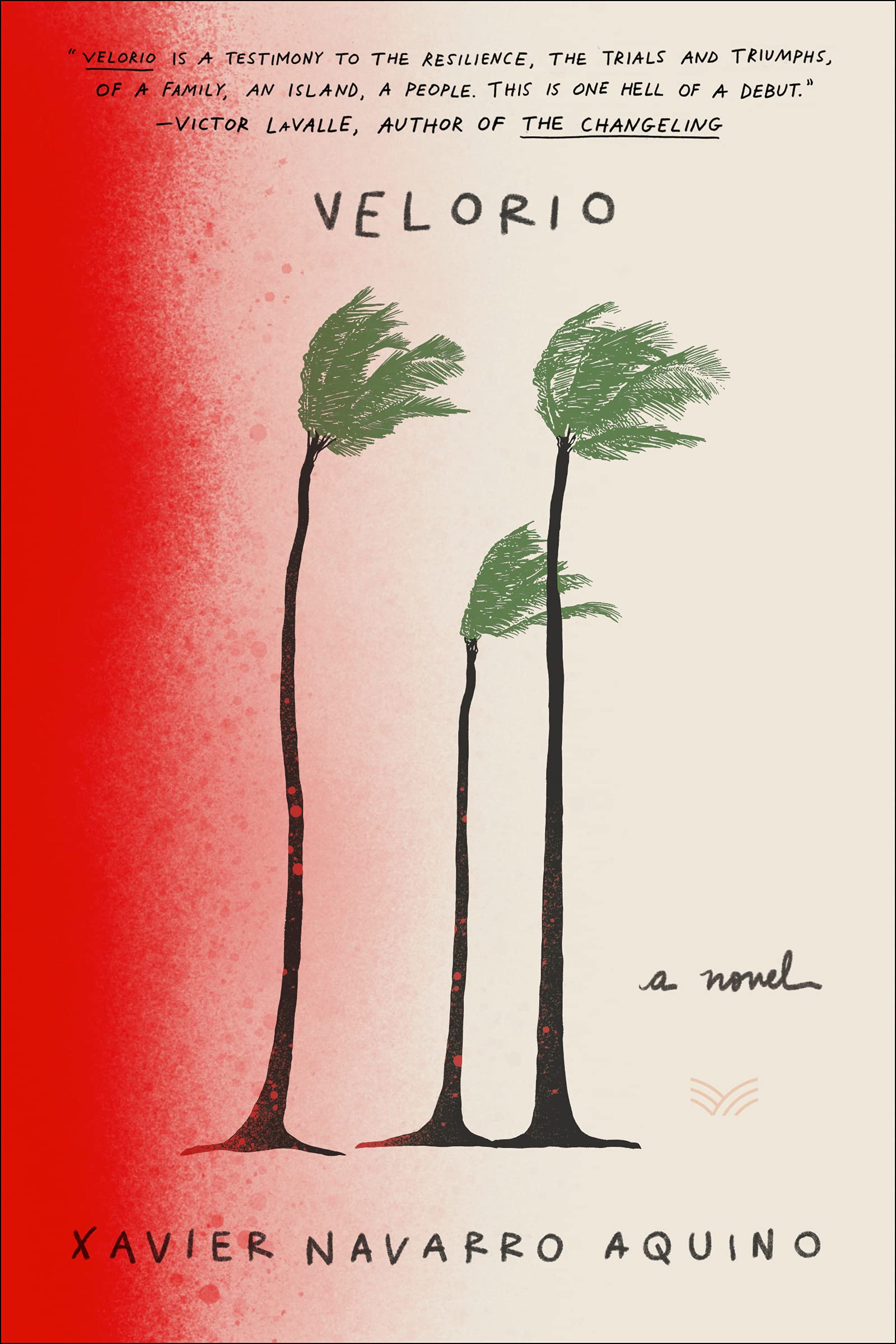

Excerpted from: Velorio. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2022 by Xavier Navarro Aquino.