Zenaida ignored the metallic taste of her thirst and the nausea surging inside her, determined not to let her symptoms get the better of her. She wrapped her hand around the pencil, disregarding her employer’s advice about how to position her fingers when writing.

The occasion arises and decides what occurs.

Her crooked letters stained the notebook paper like a scandal. She copied the words again on the next line, paying attention to the spelling of the original phrase written in the woman’s perfect penmanship.

The occasion arises and decides what occurs.

Her apron strings came undone behind her with a tug. Isabela had been untying them lately, delighting in the repetition.

“Zena, why is your handwriting so bad?”

The girl grabbed a plastic cup and tried to slip it into her pants pocket.

“Making trouble out on the terrace, kiddo? Don’t come crying to me when you get worms again.”

Zenaida intuited that the worms living inside the girl came from the thick shake she drank every afternoon on the balcony.

Zenaida had heard it a few times already, the shout that reached the kitchen from the second-floor bathroom, announcing the arrival of another worm. Ever since the girl’s mother was promoted at the bank and started coming home later and later, the cries had been directed at her. Isabela could feel the worms slide between her cheeks with the urgency of someone searching for light. Then they would fall angrily into the toilet and the girl would shout and flush, victorious. She imagined them being sucked through the vortex of Bogotá’s sewers, passing from whirlpool to whirlpool until they reached the Magdalena River. Her mother had explained to her that all the bathroom pipes emptied out there. On a trip to the lowlands, she had shown her the river winding through the valley from above, and it had been so dazzling that Isabel could hardly believe she was looking at the final resting place of the entire sewage system. Zenaida intuited that the worms living inside the girl came from the thick shake she drank every afternoon on the balcony. She’d seen Isabela’s secret ritual of mixing dirt from the geranium pot into a glass of water with a spoon she would later retrieve from under the planter. But she’d decided not to say anything to the girl’s mother.

“Zena, why do you write your boyfriend so many letters?”

*

Into Isabela’s pocket went one of the shiny spoons from the dining room table, the good ones her mother didn’t let Zenaida wash with steel wool. The ones she used secretly at daybreak to eat her breakfast while everyone else was still asleep.

“Not one of those, sweetie, the dirt will scratch it all up and your mother will kill me.”

She handed her a dull spoon from the drawer of ordinary cutlery meant for the two of them, sealing their complicity.

Isabela drank her dirt juice in slow gulps, with the sadness of beginning something that will end. She let the glassy pebbles scratch her molars and passed the lumps through her front teeth to break them up a bit before swallowing them. She felt that mix of horror and ecstasy she always liked to finish off with a long, deep shudder.

Zenaida went on copying her employer’s neat script, which spelled out a sentence meant to help her write better. A perfect sentence for practicing the difference between c and s and k. A confusing sentence taken from a book. She had explained to Zenaida that it was good to get in the habit of looking up unfamiliar words in the dictionary. She had left one for her in the kitchen.

Arise:

\ ə-‘rīz \; arose\ ə-‘rōz \; arisen\ ə-‘ri-zən \; arising\ ə-‘rī-ziŋ \

Intransitive verb

1a: to come into being or to attention

1b: to originate from a source

2: to get up or stand up: RISE

3: to move upward: ASCEND

Her spelling had gotten much better than it was when she’d started working there two years earlier. But she still confused c’s with s’s and k’s. Okasion. Deside. No. So when she couldn’t make up her mind, she thought about Marcela’s name. Marcela is with a c because it sounds like an s but comes before an e. As part of her spelling lessons, her boss would correct the messages she would jot down when someone called the house during the day. When Isabela spent afternoons hovering around the kitchen, keeping her company as she trimmed peas and ironed shirts, the little girl would find scraps of paper with Zenaida’s clumsy handwriting crossed out in red pen by her mom. Please call Miss Claudia at the offise, with the right letter announcing itself on top. She would tuck them into her pocket for her collection.

“Why is it so hard to spell good?”

Isabela wanted to know why Zenaida’s writing was so bad, since her mom said she had all her papers right.

“I write like this because I only got to fifth grade. But you’re going to go all the way through, kiddo, so you’ll be able to teach me plenty.”

Zenaida once told her that her father had pulled her and her sisters out after fourth grade, saying that women who knew too much ended up on the streets. That all they’d learn in school was how to write letters to their boyfriends. What she didn’t say was that when his poncho got caught in the wheel of his motorcycle, strangling him, his death had felt like a liberation. Zenaida and Nubia left Teorama to find work in Bogotá. A cousin got them jobs with decent people who paid on time and respected their days off. Marcela left home around then, supposedly for Bucaramanga, and they hadn’t heard from her in a long time. When the rumor reached them that she’d joined the guerrilla, Nubia and Zenaida made a pact never to talk about her to anyone else. Their mother never said her name again. Now that Isabela had started asking so many questions about her family, Zenaida was tempted to tell her about Marcela. One day, she’d even thought of the sentence, I have a sister I haven’t seen in a long time who I think about always, and even though she’s playing dead, I know she’s alive. But like the vomit that kept announcing its presence and never arrived, she’d held the words back. That was around the time the whole story had almost come out. The girl had asked what a guerrillero was and she hadn’t known how to explain it.

“Someone who goes into the mountains looking for work and gets caught up in things.”

Isabela wanted to know why Zenaida’s writing was so bad, since her mom said she had all her papers right.

Every morning, once they seized control of their respective homes and could play vallenatos full blast to rattle all the objects that surrounded but didn’t belong to them, Zenaida and Nubia spoke on the phone. Temporary owners of carpets and formal place settings, they talked about the small humiliations of their days and made plans for the weekend. Sometimes they speculated about Marcela. They’d made a ritual of imagining her brave and agile in faraway wars, surviving in huts, sleeping in a hammock somewhere in the mountains.

The occasion arises and decides what occurs.

Zenaida filled the last line on the page. The wristwatch the girl had given her for Christmas said it was four o’clock. She needed to go buy milk and eggs and get dinner started before Robby came home.

“Okay, Isa, turn off the TV and come with me quick to the store.”

Isabela was busy ignoring her mother’s double prohibition against going into the servants’ quarters and watching soap operas.

“Look, Zena, this lady’s husband died and she fell in love with his twin brother because he looked just like him.”

Zenaida’s room was big and comfortable. But it was so close to the kitchen that it sometimes filled with smells. Back when her employer’s mother used to visit, she would poke her head in and tell Zenaida to always keep her door closed. She would repeat that garlic was an aphrodisiac and terrible for a woman’s health. Zenaida made Isabela eat a clove of raw garlic every time a new worm came out. To scare off the ones that were still inside.

“Come on, kiddo. Let’s go look for Más.”

She couldn’t promise they would see the dog today. For years, Más had kept the porter of the building across the street company on every afternoon shift. But he hadn’t shown up in days. The neighborhood security guard had told the children on the block that they’d taken him to a local pound where they electrocuted all the stray dogs they caught, but Zenaida tried to convince Isabela that he’d fallen in love and was just busy. Maybe he’d come back. Isabela had begun to suspect that Zenaida was lying to protect her feelings, but she still saved the hearts and wrinkled feet from the chicken stew for Más in a container in the refrigerator, awaiting his return. Some nights she cried for him, burying her face in the pillow so no one would know.

Zenaida put on a pair of jeans and unbuttoned her pale-blue maid’s uniform to pull a sweater over her head. She couldn’t understand how the women who worked in the other houses around the neighborhood weren’t ashamed to go outside in their pastel uniforms. From the bed, Isabela fixed her eyes on the white lace bra cinched around Zenaida’s back that day.

Zenaida made Isabela eat a clove of raw garlic every time a new worm came out. To scare off the ones that were still inside.

“Let me open it, Zena. Pleeease?”

Isabela had taken to standing on tiptoe and unfastening her bra through her uniform while she was cooking or doing the wash, leaving it to float under her clothes. Accustomed to these daily rituals, Zenaida responded with stoic patience, retying and refastening the knots and clasps the girl undid over and over again.

As they left the house, Isabel reached for her hand.

“Why is it so dangerous to leave the house by itself?”

“It’s not anymore, not with the new grates they put on the windows. And since they fired the porter over in that building, the neighborhood is going to be safer, I think. He stole even worse than the others.”

As they passed the security booth on the corner, the girl bent down to perform another ritual she had recently invented. She scooped up the chewing gum the afternoon watchman had spat onto the ground when he arrived for his shift. Having spied on him from the terrace for a long time, Isabela knew that after he put on his brown security-guard uniform and combed his hair, he would get rid of the warm, saliva-drenched bubble gum and start his workday. She took advantage of any outing to retrieve the dry, secondhand gum and soften it in her mouth.

“Isabela! What are you eating now, little piggie?”

“Gum.”

Isabela concentrated all her energy on moistening the stiff purple rubber she was fervently chewing.

“It fell out of my pocket. It’s grape.”

“That’s disgusting, Isabela. Don’t pick things up from the ground like that. You know, I have a friend who ate so much junk, grass, and dirt, like you, that she got pimples all over her face. She ended up looking like an ear of corn.”

Isabela considered spitting out the slimy lump, despite her almost overwhelming urge to swallow it whole. Instead, she focused on chewing it as they walked down the cobblestone street that brought them right to the supermarket.

After paying, Zenaida approached the bagger. “I’ll see you soon. Call me.”

Isabela watched them angrily, dying to tell them she knew everything.

“The pimples your friend got, are they like the ones that man has?”

“No, sweetie. One day I’ll tell my friend to stop by so you can see what I’m talking about. And you won’t go near that junk ever again, that’s for sure.”

“I know stuff about you two, but I won’t tell you what.”

*

In the afternoon, after Robby got home from school, Isabela proposed making a cake. She’d decided to stop playing naked in the backyard after her brother said it was lame. Zenaida had taught her how to make marble cake, and Isabela had gotten the idea that she could sell slices around the neighborhood one day and buy her something nice.

“No, sweetie. I just cleaned the kitchen and I don’t want you making a big mess in here.”

Robby was singing the song Isabela hated most in the world. It always made her cry. It was a simple melody about a lonely donkey that carried his load into a thick forest in search of his master. The animal desperately wanted to find him, to make him happy. His master never appeared, and the donkey got lost in the fog and the woods.

“And no one ever, never ever, saw him agaaaaaain.”

Robby held the last note for a few seconds, in the high pitch of a child just entering the sadistic phase. The donkey’s bravery tormented Isabela. She’d asked Zenaida why the donkey was alone if he was so kind. Who had loaded him with fruit just to let him get lost? Why wasn’t anyone waiting for him? Why didn’t anyone go look for him? Zenaida hadn’t been able to answer any of these questions.

“I can’t hear you, I can’t hear you, I can’t hear you.”

Zenaida had shown Isabela how to cover and uncover her ears quickly and talk in a loud voice when someone was bothering her. It was the most important piece of advice she’d ever received.

“Give me a break and don’t make her cry, will you? Come on, sweetheart, come keep me company while I get dinner ready.”

Isabela sat down at the kitchen table and started scratching the color off the fruits printed on the plastic tablecloth with a knife. Little by little, she forgot about her grievance. She told Zenaida that they were going away for the weekend and her mother had said she could invite a friend.

“So I’m going to tell her I decided to invite you. Want to come? There’s a pool. Sayyessayyessayyes.”

“I can’t, sweetheart. I have plans. Why don’t you invite someone from playgroup, or your cousin Karina?”

Isabela imagined Zenaida spending the weekend with the bagger from Olímpica and made herself shudder.

Her mother’s car announced itself with the sound of a buzzer the girl had learned to identify. Zenaida ran out to the garage. She opened the locks, removed the chain, pushed back the bar, and swung open the gate to let her pass. From the doorway, Isabela saw her mother sitting in the car, taking longer to get out than usual. She noticed the heat coming off the motor, the fan running under the hood, the smell of cement and gasoline. She waited for her to come inside, ready to tattle on Robby for the song. She wanted to say, “Tell him, Mom, tell him he can’t never sing me that song again.” But her mother stayed in the car, carefully drying her eyes so her makeup wouldn’t give her away. Until she finally got out and Isabela heard her heels clacking over as if nothing were wrong.

They ate in silence. Robby happily devoured the meat on his plate. Isabela put hers in her mouth, chewed it a little and pretended to swallow, then slipped it into her napkin, hoping to give it to some dog. When Zenaida cleared the table, she heard her employer on the phone, explaining the tears she’d been hiding.

“He was on the plane with the bomb. They released the list, and his name was on it.”

*

On Tuesday, Robby told Isabela that Raimundo, that friend of their mom’s who sometimes invited them to his country house where the parrots could sing love songs, had been on the airplane that blew up. Zenaida knew some of those songs too. That afternoon, Isabela helped her wax the floor, using her feet to scooch a rag across the parquet.

“Zena, have you ever had a friend die in a bomb?” “No.”

Zenaida thought about all the explosions that must have gone off around Marcela in the mountains and almost said, “Maybe.”

Out on the terrace, Isabela broke up the lumps of dirt in her shake between her teeth. She looked for some sign of Más on the block, imagining him turning up suddenly on some corner, with his wise gaze and confident walk. She gulped down the final and most prized sip of her shake to run and answer the telephone.

“Zeeeenaaaa. It’s some guy named Jairo for you.”

“Tell him I’ll be right there.”

Isabela made herself shudder. She left her ear glued to the receiver the way she’d done with all of Zenaida’s calls since Robby taught her how to spy without getting caught.

“How are you?”

“I’m okay. Every little thing sends me running to the bathroom. The worst is, I don’t even throw up. I still haven’t been able to say anything to my boss.”

“But you told your sister?”

“Yes, this morning. She said I should get ready because men always split when they get this news. Promise me you won’t disappear on us when the baby comes.”

“My love, I’ve told you a thousand times. I’ll do my part.”

__________________________________

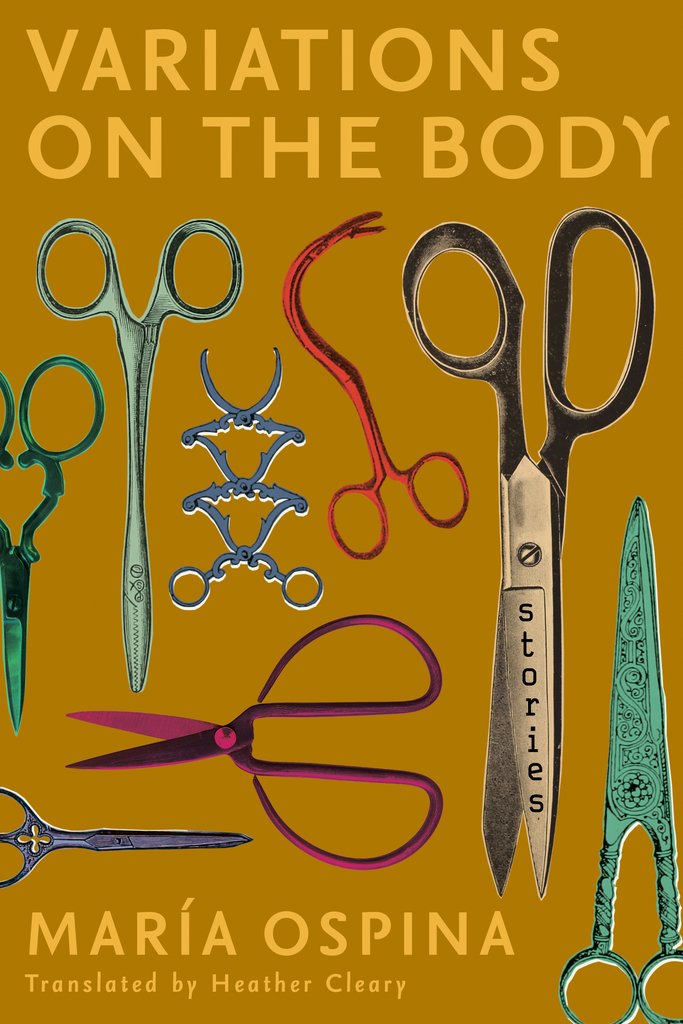

Used by permission from Variations on the Body: Stories (Coffee House Press, 2021). Copyright © 2021 by María Ospina, translated by Heather Cleary.