The first time I actively sought out the company of trans people came after I gave up on the idea that I was going to solve the problem of wanting things by sitting alone in my room trying as hard as I could not to want anything. It was a terrible, dizzying day; I wanted more than anything for solitary despair and self-recrimination to provide me with the tools to build a bright and livable future, never mind that solitary despair had never produced anything for me but additional solitary despair. I snuck into a local trans support group well after the meeting had started in an act of complete surrender, having given up yet again on the fantasy of the successful operation of crisis management.

Progress looked, once again, like regression: I had failed to cope, failed to maintain a secure and sufficient cisgender sense of self, failed to force peace upon myself. I was emotional, embarrassing, bewitched, bothered, and bewildered. Worse still, my greatest fears were realized when I entered the room: I felt comforted in the presence of other trans people. It was not that I felt immediate kinship and recognition with everyone in the room—many of us had relatively little in common, some of them I liked and some I did not—but the effect was nonetheless immediate and came in the manner of a reprieve after a long day’s thankless work. I experienced relief, when I had not come seeking relief but resolution and a promise that the mountains would return to their original position at my command. The 46th Psalm and the Friday night meeting of trans Californians served as a necessary reminder that the mountains do not move under my imperative, and that safety cannot ever be reached in trying harder to make sure my orders are obeyed by things that fall outside of my personal power.

Jesus in the Gospels tells a number of stories about the kingdom of heaven, sometimes also the kingdom of God; whether the two are interchangeable or merely closely linked is a matter of some debate. He does not spend a great deal of time explaining what the kingdom of heaven is, but in alerting others to its presence. It is like a seed, it is like a net, it is like a pearl of great price hidden in a field, it is like yeast, it is like a merchant who comes across a pearl of great price hidden in a field, it is like a king preparing a wedding-banquet and his uncooperative guests; it is near at hand, it is more than just near at hand but currently present, it is an internal condition, it is an external system of justice, it is expansive, it is restrictive, it is the enemy of wealth and tightfistedness, it is a gift that God takes great pleasure in giving, it is the engine that metes out not just justice but retribution and more than retribution, terror, it is mysterious and far-off, it is like children and for children, it is for the childlike, it is seen and unseen, capable of sudden and rapid growth, bursting through and out and up, continually emerging and becoming more of itself, more real by the second and already real, all-welcoming and difficult to enter. The Parable of the Sower reads:

Listen! Behold, a sower went out to sow. And it happened, as he sowed, that some seed fell by the wayside; and the birds of the air came and devoured it. Some fell on stony ground, where it did not have much earth; and immediately it sprang up because it had no depth of earth. But when the sun was up it was scorched, and because it had no root it withered away. And some seed fell among thorns; and the thorns grew up and choked it, and it yielded no crop. But other seed fell on good ground and yielded a crop that sprang up, increased and produced: some thirtyfold, some sixty, and some a hundred.

And He said to them, “He who has ears to hear, let him hear!

–Mark 4:3-9

This served as a guidepost to me throughout various moments of heartsickness and fear and doubt and hope and joy along my transition, which grew more real by the second and as a result more real retroactively, which was all-welcoming and difficult to enter, which was seen and unseen, capable of sudden and rapid growth, bursting through and out and up, continually emerging and becoming more itself. I often thought, too, of Dorothy Zbornak and her exit from the Golden Girls, a show about I often watched on repeat in the evenings when sleep became impossible and sometimes in the afternoon when everything else seemed impossible too. I’d grown up watching Rose and Blanche and Dorothy and Sophia in reruns, but somehow I’d never seen the series finale or had any sense of how the show had ended.

My friend attempted to remind me that it was perhaps not especially useful to assign an old sitcom the job of reassuring me that everything was going to be okay.I’d been dimly aware of the existence of Golden Palace, the single-season spinoff that didn’t feature Bea Arthur, who played Dorothy, but I hadn’t expected that the last episode of the Golden Girls would actually show her leaving. One afternoon a friend of mine came over to keep my company and we spent a few hours watching episodes from first two seasons of the show. I had to leave the house to run an errand, and when I came back my friend was watching “One Flew Out of the Cuckoo’s Nest, Part I,” which I assumed was still part of the early series run. All I knew was that it was a two-parter that featured Leslie Nielsen. I figured, based on the title, that there’d be a strange, farcical spell of some form of institutionalization, like David Duchovny’s arc on Sex and the City, and I thought that was sort of a strange direction for the show to take in a two-episode run, but I generally like Leslie Nielsen’s work and had a lot of faith in the Golden Girls’ writing staff, so I went with it.

It was a fantastic arc, maybe two of the best Golden Girls episodes I’d seen, even though the plot was absolutely bananas. Dorothy and Nielsen’s Lucas pretend to get engaged to cheese off Blanche, only to actually fall in love with one another. Oddly, no one else in the cast ever discovers that their engagement started out as a put-on, so when they get engaged-for-real a second time, all the other girls just sort of shrug and accept it as a quirk. Dorothy’s ex-husband Stanley drives her to the church and offers her his blessing in the form of a rambling monologue about his hairlessness:

Do you see this hair? It is the only one on my forehead. The other traitors receded years ago, but this proud and loyal sprout clings desperately. It is unrelenting. It is true. Dorothy, it is this hair I hate more than all the others. It mocks me. Don’t you see? I am that hair. And you’re my big, crazy, bald skull. I may give you some reason to resent me, but you cannot shake me. I am loyal.

One of the things I’d feared most about starting testosterone therapy was the idea of losing my hair, that I might arrive to manhood late enough that its first fruits would be male-pattern baldness, that I would have made a foolish bargain trading away being a reasonably-pretty woman for a single proud and loyal sprout of hair mocking my head. Dorothy’s response to this man is, as always, dry, fond, and exasperated, utterly uninterested in humoring male vanity by avoiding the truth: “Stanley, you wore a toupee for 27 years.”

And then she marries Leslie Nielsen, and then she moves away. That’s the end of the show.

I kept watching in increasing confusion, thinking, “They’re going to have to come up with some reason to get rid of him really fast, because I know the next five seasons of the Golden Girls don’t prominently feature Leslie Nielsen as Dorothy’s husband Lucas, who lives next door and is always stopping by for iced tea and cheesecake.” But they don’t get rid of him; he marries Dorothy and they move away. I didn’t know the end was coming—I didn’t even know what I was watching was the end of something. I proceeded to entirely lose it, and started sobbing in front of my friend. We had watched the pilot episode only a few hours before. I had thought we had more time. In the very first episode, Blanche almost moves out of their shared home to get married, but her fiancé turns out to be a bigamist and a con artist who gets arrested right before the ceremony. Blanche takes to her bed for three weeks. She finally comes out of her room to talk to the rest of the girls:

BLANCHE: At first I wanted to give up, to die, truly. Only time I ever felt worse was when George died. But then I had the kids with me and I pulled through it. This time, I thought, “This is my last chance, my last hope for happiness.” I just thought I’d never feel good again.

SOPHIA: How long is this story? I’m 80. I have to plan.

BLANCHE: This morning I woke up and I was in the shower, shampooing my hair, and I heard humming. I thought there was someone in there with me. No, it was me. I was humming. And humming means I’m feeling good. And then I realized I was feeling good because of you. You made the difference. You’re my family, and you make me happy to be alive.

ROSE: Let’s drive to Coconut Grove for lunch.

BLANCHE: Okay!

ROSE: My treat. We have to celebrate.

SOPHIA: What, that she came out of her room?

ROSE: That we’re together.

DOROTHY: And that no matter what happens, even if we all get married, we’ll stick together.

ROSE: Then we’ll need a much bigger house.

DOROTHY: Sure, Rose.

And I kept trying to explain that to friend, through tears, that I felt betrayed by a long-since-cancelled sitcom about a house of retirees. That show, that particular vision of retirement, had promised me something, implicitly, or rather through that show and other visions like it I had promised myself something I could now no longer keep. My security had rested in a sort of negotiation with compulsory heterosexuality such that when all my friends had outlived their husbands, we’d all get to move in together and eat cheesecake and wear comfortable loungewear for our seven extra statistically-predetermined years of life. Whatever else might change in life, we could at least count on that. And that even if we got married, even if we married men, we weren’t going anywhere in terms of our relationship to one another; the show wasn’t called The Golden Placeholders Until I Meet Leslie Nielsen. It was a negotiation that existed primarily in my own fantasies, of course, but it was a load-bearing fantasy, and the architecture of my mind suffered from the loss of it.

One no longer has to fight battles after giving up; something new can happen then.I’d never hated Leslie Nielsen before—I thought the Naked Gun movies were overrated, but I didn’t blame him for that—but Lord, did I hate him then. He tugged Dorothy through every door in every scene. You could barely keep him in a shot. He was always disappearing just out of frame. Let’s get a move on, let’s get out of here, time’s a-wasting. What are you in such a hurry for, Leslie? There’s no rush. Sit down in the kitchen with the girls and have some iced tea. I didn’t mind that Dorothy got married, but I minded that he took her away from that kitchen table. There was room at the table for him, if he’d just pulled up a chair and sat down.

Later that day I tried looking up Golden Palace to see if it would cheer me up, but then I read the plot summary of its own series finale: “Following the cancellation of the series, Sophia returns to the Shady Pines retirement home, appearing as a cast member in the later seasons of Empty Nest. What become of Rose, Blanche, and the hotel is left unresolved.”

My friend attempted to remind me that it was perhaps not especially useful to assign an old sitcom the job of reassuring me that everything was going to be okay, that transition would not take me out of my place in the world or in the lives of the people who loved me, that intimacy does not require total personal immutability, but I still felt for all the world like Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre upon learning that Mr. Mason has arrived, that all of his plans and hopes for the future have come to nothing, that the full force of his past is coming back to claim him, that his attempts to force Jane into the shape of a wife through the sheer force of his desperation and will must prove ultimately fruitless–

“Jane, I’ve got a blow; I’ve got a blow, Jane!”

Later I ended up calming down enough to go back to an earlier episode, one where Rose and Dorothy enter a songwriting competition and write a jingle about Miami. I still knew the blow was coming, but once you’re prepared for the hit, you can get into position and wait for the force to pass through you. On the other side of sobriety, my life was not given over to a daily battle against the desire to drink; after starting to transition my life was not given over to a daily battle against the desire to be a man. One no longer has to fight battles after giving up; something new can happen then. Once you accept that you’re going bald you can start to look for toupees, once the mountains are in the sea you can stop imagining they’re going to move at your command, once the blow hits you are free of the dread of the blow, and you can start to mend from it.

__________________________________

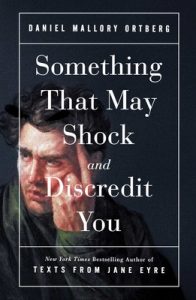

Excerpted from Something That May Shock and Discredit You, published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2020 by Daniel Mallory Ortberg.