There is no documentation for these narratives. Call them what you wish. This cannot be fact checked. There are no police reports/medical examinations/official statements/newspaper stories. No proof in the way that you want proof. No paper trail. Only story. That’s what women have had forever. How can we ascertain whether any of this is true? Where did your friend/cousin/sister/teammate tell you this? She told me in the bleachers/near the lockers/in the gym/in my car/in the dorm room/with the candles lit/in the driveway/on the train/in the parking lot.

This is not he said/she said, because we said these things only to each other. Every day, in the southern California city where I was born and still live, I drive past the places where we were attacked. Passing the parking lots where my friends and I were in cars, I remember the silver mushrooms of the door locks. We took rides home from football games and house parties. Gas, grass or ass—no one rides for free. I remember the bumper sticker on vans, cars, trucks. Does this hurt? Does this hurt? What about that? Not murmured in apology, but in anticipation. We were 14. We did not ride for free. We were told if we walked home, worse could happen to us.

I drive past the bleachers at the park where my brothers played Little League. I worked the snack bar because girls didn’t play baseball. We sold snacks. In the dark storage room behind the bleachers. I was 12. The two boys only a year older. First base and you can go. Do boys still use that term now?

I write this because women asked me to. Last year, I finally put into narrative form some stories of my life and my friends, cousins, relatives. I was told the essays could not be published because they could not be fact checked, and the phrase I learned as a college journalist, even as men were groping and attacking me then, came back like a finger poked against my spine. The details we remember? Insignificant. The events themselves, if we told someone, if we asked for help, would have been deemed insignificant, because we were insignificant as girls, and then women. Now years have passed, so the details cannot be verified. But we told each other. What we remember is rooted in the body and the senses: Dr. Christine Blasey Ford remembering her bathing suit, E. Jean Carroll remembering the lace of the underwear she was holding, the young women remembering the exact painting on the wall of the “massage room” of Jeffrey Epstein, and now that he is dead, there is no he said/she said. There is only the bravery that they told someone what happened.

I am 58 years old. Weekly I drive past the parking lot where at a broken cement stop, my 15-year-old friend and I sat side by side, our knees before us in our shorts, as it was summer, while she told me about the boy who’d raped her the night before. He was two years older than we were. He knew exactly what he was doing. He gained her trust over weeks. He talked more than any other boy we knew. She put her forearms on her knees and put her face into that cradle and I remember the back of her neck. That was 1976. I believed rape inevitable, and I didn’t want to have a baby by someone who attacked me, so I went to Planned Parenthood.

In their testified memories, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford was 15, and Judge Brett Kavanaugh 17. They spoke quite separately, their sentences braiding together in vividly different threads. They grew up in the same place. They have friends and acquaintances who brought forth their own memories. It seems undeniable that something happened, on that night. The only written record was a calendar kept by a high school boy. Often, men confronted with the memories of sexual violence recalled by women deny them altogether, as if we fabricated not only the hurt but the entire night or series of weeks or months or years. That never happened. I was never there. She is mistaken. Her very existence is called into question. It’s as if two cars collided, both were damaged, but one driver insists he and his vehicle were never even at the scene, though the other car is smashed and dented and sometimes, completely totaled.

I remember this distinctly: the music was so loud no one would have heard me scream.What were you wearing/drinking/thinking/expecting/when you went to the party? What did you say to make him think that’s what you wanted/what was he led to believe? We were in the wrong place of our own accord: meaning we entered a structure while alive and expecting nothing. I remember strange details about one house party. New Year’s Eve, 1977. My future husband and I were high school seniors. The house in a neighborhood wealthier than ours, abutting the foothills of our southern California city, more than a hundred people, dancing inside, moving through the kitchen, congregating to drink in the front yard.

A man staggering across the street toward us, maybe 25, older, with black hair in long wings down his face and neck, bellbottom jeans, blood covering his right hand, dripping from a cut. I was the kind of girl who corralled him quickly before he could get in trouble with the athletes, including my boyfriend. We were black, white, Mexican-American, Japanese-American. He was olive skinned, delirious, mumbling. I steered him inside the house, into the bathroom. I remember the beautiful gilt-edged mirror, so 1970s. I propelled him by the elbow toward the sink, and quickly he turned, locked the door, and grabbed my breasts, covering the front of my white sweater, featuring thin gold-thread horizontal stripes, with bloody handprints. (My first thought: Damn, I paid $17.98 for this sweater! Most of my paycheck for the week!) (My second thought: He’s going to rape and kill me.) He broke a perfume bottle on the sink and stood there, daring me to move. I don’t remember what he said, because I didn’t look at his mouth, only at the blood dripping on the white shag rug and the jagged glass thrust toward me.

I remember this distinctly: the music was so loud no one would have heard me scream. After what seemed like hours, the hand holding the glass slanting back and forth like a cobra’s head, boy pounded on the door shouting, “Who the fuck is in there? We gotta drain the lizard! Are you girls in there putting your fuckin makeup on? Open the door!” Then they broke it open with their shoulders. Baseball players. I still see the face of the first baseball player, golden brown, and his curly natural; I still see him now and then in my city. He saved me. They punched the man, dragged him outside and called the police. But none of the officers asked me anything. They took him away without speaking to me. My future husband was angry that I’d been so stupid. Someone gave me a letterman jacket to cover the blood on my breasts, because he said it made him feel sick. But I had to give it back before my future husband took me home. If we were in a car or workplace accident, or military battle, or natural disaster, we would be “in shock.” My teeth chattered in the silence. At home, I washed my sweater that night. Dried blood is hard to get out, but I had three brothers. I was good at bloodstained laundry. I wore that sweater for years.

I remember the places. Sewer pipe on the elementary school playground/back seat of a car/front seat of a car/stairwell in college/dorm room/office of a teaching assistant/lab of a chemical engineer at work. I remember the college-educated chemist 30 years older than me, as I was 20, held the back of my bra as if it were a harness and I a small horse merely trying to get across the room to do my work. He was out to prove I couldn’t leave until he allowed me to. He said, every time, that he was merely checking to make sure I was wearing a bra. That reminded me so vividly of sixth grade I didn’t even know how to react, and then I just refused to go into that workspace and was disciplined. I do not remember the dates, or the floor of the building. I remember the beakers on the counter.

*

What room of the house/seat of the car/kind of carpet/part of the couch/area of the yard/end of the pool/section of the bleachers/corner of the store/row of the theater/where the alleged assault took place? Was it a twin bed/queen/king? What was the day/week/year/time? What was the make and model of the car/truck/van/camper? The address of the house? Which bedroom? How many bedrooms were there? (Did we girls ask that question the minute we arrived at the party? Did someone give us a tour, so we could identify the master bedroom, the bedspread, the bathroom? Should that be standard?) How many people were there? (Guest lists, also standard?) What time were you taken/forced/carried/or did you voluntarily go into the bedroom/bathroom/garden shed/kitchen/basement/closet/office/laboratory? Who saw you enter that place? Who saw you leave? If you were hurt, how were you able to walk?

Every time I hear the song “Sexual Healing,” by Marvin Gaye, and it is played often, I remember another high school friend in my car, angry and then weeping. The song was new. She reacted violently, telling me to turn it off. She said the lyrics were disgusting. She whispered the words that made her cry. You’re my medicine/Open up and let me in. An adult in her family had forced his way into the place where she slept, and raped her. She was so shaken hearing those words, and I was so shaken when she told me, that I turn the song off, even now.

Every time I enter my kitchen, I remember a woman sitting at the maple table my mother bought when I was three. Eight years ago, both of us grown, she told me how her mother had been assaulted repeatedly by an adult man when she was a girl. Ten years old. Her mother told no one, until one morning the girl couldn’t walk to school. She had advanced syphilis. The woman said, “They never told us who he was! And later same thing happened to me. But I told! I told them!” She told only her mother and grandmother.

This is what my cousin did not say. Let’s review/Let’s make sure you have your story straight/Let’s go over this again.Why didn’t you report this? I did. Who did you report it to? My sister/mother/aunt/grandmother/cousin/friend. What did that person do? She listened/cried/hit me/hugged me/washed me/cried/combed my hair/washed sewed dyed dried burned my clothes/cried/shook her head/said she knew/said that couldn’t be true/said she’d kill him/said he’d kill me/said get in the car/said we’ll never tell anyone/said I love you.

We could tell you: the smell/gum/whiskers/one finger/two fingers/three/fingernails/rings/song/engine/bedspread/the smell/carpet like stiff worms/carpet like cement/burns on our shoulders/above our hipbones/our tailbones/astroturf/leather/vinyl/Naugahyde/grooved metal bleachers/asphalt/jeans/zippers/metal teeth drawing blood/human teeth drawing blood/braces/bracelets/dog tags/Irish Spring/cologne/four fingers a solid gate over our mouths/French fries/hot sauce/motor oil/there is no name for the inside of a knuckle pressed hard on our lips.

Last month, I sat with a cousin in the dim light of her living room, 100 degrees outside, security screen door letting in the noise of the street. We talked about house parties. She told me about the night when she was 12, at a house party a few blocks from where we were, and an older boy, maybe 19, bumped and bumped against her while they danced until she was in a hallway and then in a bedroom. Having been raised in Los Angeles during the Black Panther movement, she talked him out of assault by bringing up unity, the violence already done to her school and family by police, and his responsibilities to her as a young black man she called brother. That was 1970.

I told her about the 1977 house party and the sweater. We laughed about the sweater. I told her about the dorm room two years later, where a large athlete lay on top of me, threatening rape, and that I invoked our male cousin, who had an Uzi, and would arrive in the morning to shoot off the athlete’s testicles. If I told. I didn’t tell anyone, because the man removed his forearm from my throat and got up, and I left.

That was 1976. I believed rape inevitable, and I didn’t want to have a baby by someone who attacked me.Then I told her about the doctor. He might have been 50. Sixty. I was 13. I remember only: glasses shining like small lakes in the bright reflection of the high-powered light. Does that hurt? Does that? What about that? I am lying on a table. No clothes. Shivering uncontrollably in the frigid air. A tube. He stands in the doorway watching. Maybe he was filming, I realize now. Maybe just watching. My mother is in a waiting room far away. She thinks I have a bladder infection. The bare metal table is swimming with my tears, running into my hair and down my neck. He tortures me for a long time, or for half an hour. Was I restrained—by equipment, or by obedience? I have no details for that.

This is what my cousin did not say. Let’s review/Let’s make sure you have your story straight/Let’s go over this again/Let’s assume you’re not exaggerating/misremembering/dreaming/telling tale tales/being dramatic because you were a teenaged girl/menstruating/hysterical/looking for attention.

I had never told anyone, not my mother or anyone else. But this year, writing about my childhood, I remembered. I have always been afraid to go to doctors, or to the hospital. But at an appointment with a nurse/practitioner, for a possible minor surgery, the first time we’d ever met, I told her why I was afraid of even minor procedures, why I had never spent the night in a hospital since my third daughter was born, in 1995. I had that child 17 minutes after arriving in labor and delivery because I didn’t want to go inside.

I avoided doctors for so long that I got severe anemia, detached retinas, and other illnesses. We sat two feet from each other, our knees companionable. She told me that when she was four, in the rural place where she was raised, a boy had threatened her with a knife and told her to pull down her pants. She told me that when she was 12, in a field across from her house, a man pulled up in a car and asked for directions, opened the door and said things so shocking and dirty that she ran into the fields to hide. She told me that when she was a young nurse, a physician had casually affixed a sticker to her uniformed breast. She protested vehemently. Though she saw him pull other nurses onto his lap, and affix stickers to them, he never approached her again. I cried, just a little, with this woman I had known for 20 minutes. She tended to my physical ailment. I went home, grateful. That night, I picked apricots from my tree and took them to my cousin, and we sat in the heated dark room on her couch for three hours. We told stories of our aunts, our grandmothers, of razors slashing clothes, of guns pulled from coats, of girls who survived and told only each other. We might never tell anyone else. We told someone. We told a woman. We are alive. It is documented in our mouths.

———————————————

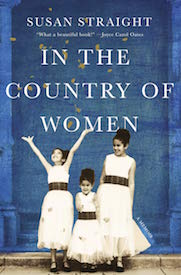

Susan Straight’s memoir, In the Country of Women is now available from Catapult.