Unspendable Currency: Edgar Kunz on Making Ends Meet As a Poet

"The job makes the real work possible. The place you live is only as good as the life it allows."

When I prop my bike against the fence and push through the half-open gate, my landlord is elbow-deep in a rose hedge and bleeding badly from his arms. Cut branches and a wash of pink petals around the foot of his ladder. It’s midday. His bungalow rises cool and white behind him. He looks like he’s conducting an appeasement ritual for some minor god. God of pricked skin, of sunburn and awkward diminishment. He startles when I say his name: Don. He is not pleased to see me. Oxford soaked through, gray hair curling around his ears, he winces and wipes his arms with a dishtowel, then wipes his forehead, leaving a streak of partially dried blood. He calls me Edward: Alright Edward. Take off your shoes. He sets down his loppers and goes in.

This is Oakland, California. 2016. Cranes on the skyline in every direction. A million for a tear-down in Rockridge. I’m living a few blocks away, a ground floor studio in a building Don owns. Enough room for my bike, a full-size mattress, a desk, and one of those tiny Ikea couches I rescued from next to the building dumpster. The studio shares a wall with a famous Ethiopian café. During the day, I can hear the whir of the paper towel dispenser, the toilet’s gurgle. At night, I can hear the dish crew dumping out the silverware and scouring the pots, chatting to each other in Spanish.

A few weeks ago, I woke to damp sheets and the smell of wet dog. The shared wall was blotted and streaked, and it kept the impression of my palm where I touched it. Burst pipe, I thought. I went over my options. What did I want? What did I think I could get, and what was the right play, the best angle, to get it? I rang Don at home and told him about the wall, and in the same breath tried to convince him to let me stay in the upstairs apartment, bigger and newly vacant, while repairs were made. I argued that it saved him having to put me up in a hotel. He was reluctant at first, hemming and hawing– but then, to my surprise, he softened. He told me to come by for the key.

White stucco, exposed beams. A kitchen of stainless-steel appliances with names like Viking and Wolf. The AC raises the hair on my legs. I make my play. I tell him about my circumstances: that I’m a poet working on a book, that I’m living on a stipend from the university– not much, but enough. And I tell him I’m in love, and we’re desperate to live together. Still dabbing at his wounds, Don says, So am I getting this right? You want me to rent you the top-floor unit. I nod. But, he continues, you want to pay less than market. Faint smile as he pours himself a glass of water, downs it, then looks at me hard. I’m losing him. I change my tune and tell him I’m making twice what I’m actually making. I say there’s a chance I stay on at the university, long-term maybe. I’m trying to convince him I’m a safe bet, that I have prospects and a clear path. I’ll think about it, he says.

It’s true I’m a poet working on a book, though progress is slow. And it’s true I have a fellowship that’s buying me time— time that, no matter how hard I work on my poems, I feel I’m misspending extravagantly. The stipend isn’t bad—a little over $30k, more than my family made in a year growing up—but it doesn’t go far in the Bay Area, so I have a few side-hustles, including reselling thrifted clothes on Ebay. And I am in love. She lives in Denver and is quitting her job at an alt-weekly. My current spot is a tough sell, but I know the apartment upstairs is twice the size at least, with double-wide windows and a separate living room. Respectable. A real middle-class apartment.

No matter how hard I work on my poems, I feel I’m misspending extravagantly.

I’ve been living minimally my entire adult life. After college, I shared a house in Baltimore with a rotating crew, sometimes seven or eight people at a time, many of us working at the same ropes course upstate. I paid $240/month. In Nashville for grad school, I shared a converted one-bedroom apartment with a family of racoons in the attic and a bachelor possum in the basement. I paid $400. Now, in Oakland, I’m paying Don $1100 for this studio – a stretch – and the rent on the upstairs spot has to be twice that. So I’m here, bargaining with my landlord among his gleaming appliances. I try not to look too desperate. I tell him I’ll wait for his call.

*

I don’t have to wait long: Don rings the next morning. I leap out of the shower and stumble around, trying to triangulate my phone by the intensity of the vibration. I find it on the bedroom windowsill. You can have it, he says, at eighteen hundred. For six months. Then it goes up to twenty-two. Breathless stumbling thanks, scheduling a date to sign the lease, then calling up my sweetheart to give her the news. We can’t believe our luck. We’re cracking up. We start getting dreamy over playing house, combining what we own. She has a mid-century bedroom set from her grandparents, I have a bed and a desk we can share. We scheme about a full-size couch. She moves in a few weeks later, shipping her stuff in a cube we go down to the dockyard to unload. On the first morning, sipping coffee, she spots a red access ladder outside the kitchen window. We climb it rung by rung and hoist ourselves onto the roof, which is coated in powdery reflective paint. We laugh at our silver hands.

*

The next years were predictable, and disorienting. I wasn’t asked to stay on at the university. I hit the job market, got a few interviews but no bites. I moved back to Baltimore, rented a friend’s spare room and adjuncted at the same college I graduated from a decade earlier. I sold a book of poems about growing up in working-class New England, my addict dad. My sweetheart took a series of residencies in South Carolina, Oklahoma, Wyoming– wherever gave her space, paid her a little to write. My dad died at 52. I went back home and cleared out his apartment with my brothers. I worked my way up at the college, making a little more money with every contract, feeling marginally more secure. I hadn’t written anything worthwhile in a year or more. I kept doubling down, forcing myself to put in time at the desk. It didn’t work. I felt drifty, useless. I threw myself into teaching, which I loved, and it was almost enough.

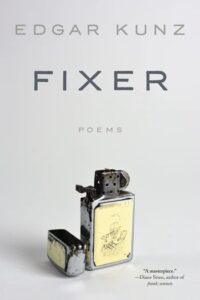

Then last winter, housesitting for friends in Vermont, I found a good rhythm, almost by accident: coffee and eggs in the morning, then getting lost in a novel, tending the woodstove, hanging out with their cat, Charles. Bundling up and trudging around in the snow. I felt outside of time, outside of my usual tedious patterns. I forgot about ambition, and I came unstuck. I wrote the middle section of what would become the new book, Fixer, in a little over a week. They were short poems, 18 lines each, and they came quickly, each scene a little firecracker going off in my hands: breaking into my dad’s apartment after his death. Finding, among other things, a sword in there. Bringing totes of his clothes to Savers. Talking to my brothers, his neighbors, his old former friends who loved him. Talking to my mom, who loved him, or a version of who he used to be. After that heady period, I was left with the harder, slower work of figuring out what else the book was about.

It’s taken me a long time to realize that my great subject, my first and most lasting obsession, is money. What we have to do to get it, how both having and not having twists us up. My first book, for all its obvious themes of masculinity and quiet suffering—for all its “grit”—is really about money. When I write about strapping a free armchair to the roof of my friend’s stepdad’s van, I’m writing about money. When I write about getting a tooth pulled at a free clinic. Cutting coupons with my mom. My brother showing me his gun. My dad in the hospital remembering a work accident, how he watched his own blood spatter the plywood floor “alien/and bright as coins/from a distant country.” An unspendable currency.

It’s taken me a long time to realize that my great subject, my first and most lasting obsession, is money.

Working on Fixer, I kept coming back to Don, his rose hedge and his bungalow. His temporary generosity. In my first book, I was bent on excavating my childhood, trying to make sense of it from a place of relative stability. I’d barely touched how that past ripples into the present and shapes my behavior– behavior that was invisible to me, and therefore a non-subject. But wasn’t there something to be said about my constant, manic hustling for a good deal? All my Craigslist schemes and side gigs and teaching myself how to solder and refinish and plant? The poet Mark Jarman says “You write about the life that’s vividest./And if that is your own, that is your subject.” My life has always been my subject– so why this bashfulness around writing about it in the present tense? And now, newly salaried and with decent health insurance, why not talk about what having even this much does to your sense of yourself, to where you feel you belong? To how your family sees you?

This small liberation led to others: I wrote about falling in love, I let myself be funny. I wrote about waking up hungover and sneaking cigarettes and worrying about artificial intelligence and watching the same Stevie Nicks video a hundred times. By the end of January, I had a draft. By the end of February, I’d sold the book—for $2500, after negotiating—to my publisher.

*

If this sounds like a triumph, it isn’t. I mean it is and it isn’t. The book happened fast, for which I was grateful and relieved. And now I’m back where I started, feeling drifty, low. I’ve inherited a set of ideas about what work looks like. Real work is exhausting, and sanctioned somehow, clocked. If you’re working, you should continuously have something material to show for it. Production equals worth, a stable identity. Stagnation equals death. Sound familiar? These are the tenets of industrial capitalism. I’d guess writers who grew up working class are more susceptible to this framing: we put in our shifts, crank out the work, strive for the next opportunity. We’re always proving ourselves. We crave legibility, some marker that says I made it.

I went into Don’s garden to get an apartment big enough for two at a price we could manage. I was desperate to have it for the extra space, sure—but also, I suspect, because it would satisfy something deep in me: I would become, by virtue of living there, a person who deserved that place. Who, by their hard work, had earned it. There is, of course, no correlation between what a person deserves and what they have. How hard they work and how much they make. And anyway, I hadn’t earned it. I could only get the apartment by scamming it, which rendered it temporary: just before the rent was supposed to go up, we left for a cheaper, smaller spot.

There is, of course, no correlation between what a person deserves and what they have. How hard they work and how much they make.

And now, having recently, by some great mystery of banking, bought a house in Baltimore—a brick-front rowhome with a garden and an office for each of us—I’m realizing that I would sacrifice it in a second if the expense threatened the time I need to write. The place you live is only as good as the life it allows.

I’ve been using my writing to hustle a life: a place to live, a salary, some measure of stability. But poetry resists those interests. It’s not about hustling. It’s not about productivity. It’s not even, in the end, about making anything. Most of us will have little to show for the hours we spend at the desk. Hardly any of our poems will be read in twenty or thirty years. Jack Gilbert says “We go into the orchard for apples. But what we carry back is the day among trees with odor,/coolness, dappled light and time.” What is work that’s never finished, never achieved? We go into the orchard for apples, and we carry back solitude and pleasure. We return, I hope, more sensitive, more humane, less susceptible to jealousy and despair. To the passing gleam of accomplishment.

__________________________________

Fixer by Edgar Kunz is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Edgar Kunz

Edgar Kunz is the author of Tap Out, a New York Times "New & Noteworthy" pick. His writing has been supported by fellowships and awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, MacDowell, Vanderbilt University, and Stanford University, where he was a Wallace Stegner Fellow. His poems appear widely, including in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Poetry. He lives in Baltimore and teaches at Goucher College.