Unmoored in a City of Ruins: On the Revelatory Power of Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren

Joss Lake Considers the Profound and Best-Selling

Science Fiction Novel

When I was in high school, I started to read Proust after seeing the word homosexual in the World Book Encyclopedia article about his work. Entering his prose felt to me like fantasy, the syntax collapsing time and the stability of the subject; it was liquid, like desire. I mean, isn’t the madeleine a most elegant time-travel machine? I didn’t read sci-fi because no one around me took it seriously. Also, I had a sense that the genre was all machines and aliens stationed at a dark horizon, and since my father’s murder, I was already acquainted with a worse future. We read according to our hungers, our blindnesses, our delights.

When I came upon Alain de Botton’s How Proust Can Change Your Life, I was relieved: Here was someone bottling up the medicinal effects of the volumes in witty glass vials. Reading de Botton’s book, it was okay to acknowledge that I wanted that languor, that desire, that freshness of perception, that gauziness of another’s life, that cascading queerness, even when I was not inside a volume.

Many hard years later, when I reached the cusp of transition, the brightness of fiction had blown out. I was grieving my father’s death for the first time, finding his body in my own. For the first time, I read memoir, trying to understand how anyone moved through entangled suffering, either at the surface—relationship problems, debts, discovering that others had different metrics for language and its purpose—or deeper. The books were too coherent to soothe. I found all sorts of practices and balms: linking back to the body, breath, compassion. I just about gave up on books as any form of medicine.

And then I entered Dhalgren.

Friends had been recommending Samuel R. Delany’s novel to me for years, as if in code. They would always stop short at its unsettling edges. A narrator, nameless. A city, in ruins. Sex in parks, on roofs. Sentences that move on their own. However appealing, I had not been able to immerse in books and I was still stuck in this aversion to “sci-fi.” The matrixes of what we read are defined by those same strident forces that shape us. They can shift. We can shift them.

To enter the city of Bellona, I left my name at the entrance, like our guide. I forgot whatever was outside. Here, as the narrator explains, “There is no articulate resonance. The common problem, I suppose, is to have more to say than vocabulary and syntax can bear. That is why I am hunting in these desiccated streets. The smoke hides the sky’s variety, stains consciousness, covers the holocaust with something safe and insubstantial. It protects from greater flame. It indicates fire but obscures the source. This is not a useful city. Very little here approaches any eidolon of the beautiful.” Once you give up on coherence and beauty, they are allowed to return, in new, strange forms.

Inside of Bellona, there are hidden instructions on how to live.

Let the Poets Be Heroic

Reading this book while away from New York, living in the city of St. Louis, which has Bellonian aspects, for sure, I’d take a break from remote work and walk my dog down to the Roosevelt High School track in the middle of the day. Training equipment—foam pads and a metal five-person sled—had been left out on the field, where the scent of cut grass was dizzying, made me lose my orientation. I passed by the red ticket box, just large enough to be a decent portal. I looked at the empty wooden stands—how, as a younger person, I’d longed to simply observe heterosexual rituals, like football games, without being a part of them. I unclipped my dog’s collar. She, who could never go off-leash in New York due to her “dog-selectivity,” raced up and down the immense field. What did this unexpected spaciousness mean to her, to me? “Home of the Rough Riders,” said the score board. Only a poet could make sense of the freedom and the despair meeting each other in this open, closed place.

In a city swallowed in smoke, where food is scavenged from trash-cans and ruined stores, certain denizens adorn themselves in chains and blades, and money is ornamental (our narrator tosses a $5 bill back at Mr. Richards in disgust), our narrator’s poetry is adored (sincerely or not), passed around, read aloud, published, memorized, referenced by characters across the entire social spectrum. The narrator, Kid(d) becomes a sort of poet-leader, with all the strangeness and violence that this entails in Bellona. In the absence of capital, (there’s certainly social capital, as in any queer land), not a single Bellonese has any reason to pretend like poetry is a waste of time.

Drop into Languorous Time

I was teaching three classes online, working in a writing center, and tutoring students, while trying to reach friends from all of my devices and write another book. Time became segmented as place—often, a modest guest bedroom in a sublet apartment in St. Louis with a record player where I’d play my Dad’s old albums—did not change. Even when I was technically off, the mental clangings, trying to figure out what the baseline of okayness was, moving from fog to sudden joy to wild worry to catastrophizing despair, continued. I started to read and from inside the book, I could remember other forms of time. I started practicing, just going to the park with my dog and noting what sort of sky emerged above us, what sorts of trees and shadows of trees.

In a destroyed place, art is taken seriously, and perhaps more importantly, our artist has time—in the bar, after sex, between moving furniture—to sink into language. There is no work to be done, outside of survival. Bellonese don’t have to “earn a living;” they scavenge, they raid, and they occasionally unearth coffee and caviar, which is always shared. In all the hours not spent procuring food or fighting (or lost to our narrator, who is told of the gaps in his memory), a languor descends: the hippies in the park play Chinese checkers and cross twigs, the scorpions sleep and brew coffee, our narrator writes or has sex, Calkins produces a newspaper, no less tethered to objective truth than anything else in the city.

Desires float through the structureless space, knocking into disaster. And there is time to watch the sky, with its second moon, its fog, its cracks. In spite of all the gaps in his memory, Kid thinks, “The sublimest moment I remember… was when I sat naked under that tree with notebook and pen, putting down one word then another, then another, listening to the ways they tied, while the sky greyed out of night.”

Do Not Pretend Violence is Otherwise

I only recently got into sci-fi, but I’ve always loved fantasy of one sort or another: books with otherworldy prose, kink, imagining other peoples’ lives, looking into the archive and trying to create a cinematic image of the past. What exists on the other side of fantasy: that which is. My family’s life was cut through by violence and yet, we could not look at it. The violence was too big and it had already sluiced over our walls before we could get any sort of perspective. We ignored it. It grew.

Violence occurs almost continuously in Bellona, like a weather system. What is unusual is its clarity. There is no coherent state shaping the violence to its needs. The scorpions, in their chains and vests and lights, are the closest structure to a police system. They presumably offer “protection” to certain groups but much of their fighting is internal. Violence (an elevator shaft incident is described in almost-unbearable fleshy detail) unfolds without euphemism or obfuscation of harm. Our narrator encounters—and enacts—brutality directly. We cannot trust the Times, fueled as it is by the eccentricities of a single man, and so, we are left sifting through the unstable fragments of memory, of encrusted bodies, of the swinging meat hooks that, one day, appear on one side of the street and on another, seem to have crossed over.

Dazzle with Your Own Strange Archetype

I want so much that is outside my body. Desire does not generally come from within me but is a mist that moves through. Being trans has not actually made embodiment easier; in fact, I long for further dimensions, accessories, valences. I just bought a pair of clogs (Poshmark), some headbands (at the grocery store), and tapered off of testosterone for a while (partially thanks to healthcare communication issues across state borders). My friends and I love to use the Snapchat elf filter. The patina of glitter feels real. That was part of my birthday; we all became elves and went on a quest together.

A projection of light, an exaggerated animal form, that would help me reach the size I’d prefer.

For all their fighting and their collective crud and crust, constantly catalogued (dry back skin, broken teeth, scars, errant facial hair), the scorpions can transform themselves with holographic projectors into animal totems. Heading to the release party of BRASS ORCHIDS, Kid, who finds the warehouse with the projectors but does not light up himself, watches as, “Dragon Lady’s dragon rose, luminous jade, ahead. The mantis and the griffin flared, swaying, with misty penumbras. An indigo spider flickered, mandibles higher than Kid’s head—flickered out once around Copperheard, then gained full brightness like tardy neon. Glass disappeared inside his newt. Spitt’s beetle glistened up like bottle glass.”

In a destroyed place, art is taken seriously.

They are given alternate dimensionality, these folks who would be likely read as miscreants outside of Bellona. In a place sunken in run-down shades, the lights are borrowed from another, brighter realm. The lights are both whimsy and serious gesture toward the fact that within this group, each individual has a particular energy and way of moving, and each Scorpion can far exceed the usual human dimensions when desired.

Don’t Rely on the Known

In this age of proliferated information, it’s hard to separate what is transmitted from what is true.

The Bellonese sky, as well as everything below it, is unknowable. One evening, our narrator walks out of the queer bar, Teddy’s, and encounters a group of people staring up at the sky, looking at a second moon that has appeared. By the next morning, the moon has been named George Harrison, after another Bellonese celebrity, portrayed by the Times as someone who raped June Richards, a teenager, by June as someone she desires. The question of sexual violence remains; the reader must hold the tension without resolution, while all over the city, posters are passed around emblazoned with a nude George in commanding positions.

Concurrent with the visit of NASA astronaut Capt. Kamp, a blazing metal disk appears to swallow up the sky.

At the queer bar, Kamp is asked about the “astrological happening” and says, “‘I think that was about the strangest thing I ever saw, I’ll be honest now.’

‘As strange as anything you saw in space?’ from the man in purple angora.

‘Well, I tell you, this afternoon was pretty… I guess you’d say, spaced out.’

They laughed again.”

Kamp admits he has no idea what is going on in the city. He defers to Tak, the engineer, who has made it clear that his scientific expertise is of no use. Point is, no expert, no external knowledge system, can decode this place. In the absence of clarity, we sit in the ruins, and on occasion, a new wind brings some sort of shape to what we see.

We are unmoored, the city is neither allegory nor replica nor fantasy.

There is a meditation practice where you stop, close your eyes for 30 seconds, and re-open them, taking in the immediate scene around you. What invariably happens is that the strokes of wood-grain on the floor, a single tuft of a throw blanket, a nick on a piece of furniture—you see them for the first time. In Dhalgren, we come to a city in ruins and we are pushed into new seeing. We are unmoored, the city is neither allegory nor replica nor fantasy. The solace offered is unusual, regularly ruptured. In the unfamiliarity, we commune with our wide, fragmented existence, rarely captured in the over-polished streets of the everyday city and discourse. We cross back over the bridge, carrying vials.

__________________________________

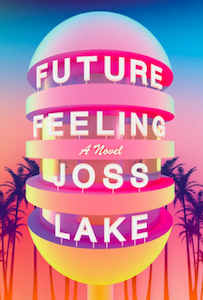

Future Feeling is available from Soft Skull Press. Copyright © 2021 by Joss Lake.