Unlearning the Sunk Cost Fallacy, in Writing and in Love

Hazel Hayes on the Power of Walking Away

It’s a grey, rainy Sunday afternoon, the first day you’ve had to yourself in weeks. There’s nowhere you need to go, and nothing you need to do but relax. You’re nestled into one corner of the sofa with a blanket and a big mug of hot chocolate, and you’ve just rented a three-hour long movie to see you through till dinnertime. It was expensive—£11.99—but you’ve heard only good things.

Ten minutes in, you hate it. It’s not what you were expecting at all. You decide to give it another ten minutes; maybe it will get better. But it doesn’t. So you spend yet another ten minutes trying and failing to like it. You’re now twelve pounds and half an hour down, you’re not enjoying yourself, and the only thing keeping you from turning this film off and finding one you’d like more is the time and money you’ve already invested. Regardless what happens now, you can’t get them back, so you really should cut your losses and focus on future outcomes instead—how you’d most like to spend this precious afternoon for example—but you’re too blinded by the belief that by investing even more in this endeavor, you can somehow recoup what you’ve already lost.

This is the sunk cost fallacy; the human tendency to continue investing resources in a less desirable alternative, simply because we’ve already invested some significant, irretrievable cost. I say human tendency because this kind of decision-making flies in the face of rational thinking—a robot would never. It was originally an economic term referring to the literal costs incurred in running a business, and the error in reasoning when applying sunk costs to future decision making, but it applies to all kinds of choices, from collective to individual ones, from the life changing to the mundane.

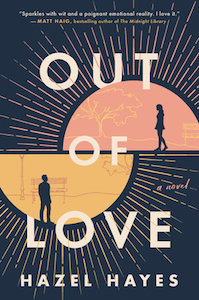

I’m particularly interested in the sunk cost fallacy when it comes to love, so much so that I wrote a book about it without really meaning to. That is to say, I didn’t have a term for it at the time, I just wanted to explore the reasons why we stay in relationships long after they’ve stopped bringing us joy, and even long after they’ve started causing us immense amounts of pain. And so I began Out of Love at the end—with a couple breaking up—and moved backward through their story to when they met and fell in love. I wanted to know how they’d got to this point and figure out when it stopped being right, or if it ever had been.

Somewhere in the middle of the book, the narrator is asked what seems like a straightforward question: If you’re not happy with him, then why do you stay? She replies, “You make it sound so simple… But there’s this paradox with relationships, isn’t there? The more time you’ve spent trying to make it work, the more time you’re willing to keep spending, trying to make it bloody work. I stay because I genuinely believe, if we both try hard enough, we can get back to the way it was before. But, I don’t know, maybe I should just accept that what we had is gone. Maybe it’s more like a building that’s been burned to the ground than some lovely home I could return to and find everything intact and in its place. Maybe I’m not willing to admit to myself that it’s just a pile of fucking ashes.”

Far better to consider the opportunities you’ll definitely miss out on by staying, than the ones you might miss out on by going.

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone; most of us have, at some point, kept going even when we knew on some level that we should cut and run. And just like we invest in business ventures hoping for, even expecting, a reward in the form of profit, we enter into relationships hoping for a reward in the form of a stable, loving partnership which brings us joy and happiness and which we can, ideally, rely on forever. We want this one to be The One, so that we can stop looking, stop dating, stop worrying about this particular part of life and focus on other things instead. So when it finally dawns on us that this one might not be The One, it’s not just the other person we need to let go of, it’s the fantasy we’ve been holding onto. We are forced to release our white-knuckled grip on that future state of potentiality which we believe might still exist. You know, the one where if you change and if they change and if you both do this thing and that thing and all those other things exactly right then maybe you can still get your reward? This is a form of loss aversion, and it’s very common in gambling; we’d rather keep trying in the hopes of winning back the money we’ve lost, than admit we lost it in the first place.

We are also, unfortunately, affected by emotions we expect to feel in the future, as well as emotions we’re feeling right now. We anticipate the loneliness, grief, defeat or regret we may feel if we walk away, and the prospect is so terrifying that it’s easier to continue experiencing whatever negative emotions we currently have in the relationship than risk feeling even worse. Better the devil you know and all that.

Then there’s the fear that conditions might suddenly change; What if you shut down your ice-cream business and suddenly there’s a heat wave? There hasn’t been one in years, of course, but who knows? A friend of mine is going through a divorce at the moment—his partner decided she doesn’t want kids and her decision made him realize how much he definitely does want a family. Even though they still love each other, they just can’t agree on this one, fundamental thing. At dinner the other night, he asked me, ‘What if I leave, and in a year or two she changes her mind?’ All I could say was, ‘What if you stay and she doesn’t?’ Far better to consider the opportunities you’ll definitely miss out on by staying, than the ones you might miss out on by going.

I’ve noticed the same thing happens when I’m writing. Sometimes, I put so much time and energy into a chapter that it’s hard to admit when it’s not working. The feeling is a lot like love, too, because I can’t always put my finger on exactly what’s wrong, I just know it isn’t right. Instead of moving on to something else, I’ll keep revising the same piece of writing over and over, picking away at each paragraph in the hopes of making my efforts worthwhile, when deep down I know what I have to do; learn what I can from it, then scrap it and move on. It’s important not to skip that first step either, because there’s always some lesson to be learned—the words that don’t make the final draft can often lead you to the words that do—and at the very least, now you know what you don’t want to write, which can be just as valuable.

I’ve just started writing a new book. I say I’ve just started, but I actually wrote the first chapter back in April. Something about it wasn’t working though, and I spent months poring over it, unable to move past this one chapter to the rest of the book. Then one day I decided to read The Writing Life, by Annie Dillard. It’s more a manifesto than a book, really, a call to arms for struggling authors, and I was struck by these words in particular; “Process is nothing; erase your tracks. The path is not the work… You must demolish the work and start over. You can save some of the sentences, like bricks. It will be a miracle if you can save some of the paragraphs, no matter how excellent in themselves or hard-won. You can waste a year worrying about it, or you can get it over with now. (Are you a woman, or a mouse?)”

“I’M A WOMAN!” I roared at my empty apartment. Then I deleted the whole chapter, made a cup of tea and started again.

Does that mean it’s never worth trying to fix something that isn’t working out? Not at all. But I think you should always ask yourself why you want to keep trying. And if the answer is simply, “I’ve already invested so much,” I’m not sure that’s a good enough reason. Especially when the conditions haven’t changed; “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting a different outcome,” said Rita Mae Brown in her 1983 novel, Sudden Death. Of course, you might still make it work, you might win your money back, you might change your partner’s mind, you might fall back in love, and maybe that awful film you rented has a cracking third act! But you must decide how much you’re willing to give to find out. Then once you’ve decided, you must be able to walk away when that limit is reached. That’s easier said than done, of course, but remember that by choosing to move on, you’re not moving on from business, or love, or writing entirely. You’re just learning what you can from this chapter, and then letting it go.

_____________________________________________________________________

Hazel Hayes’s Out of Love is available now via Dutton Books.

Hazel Hayes

Hazel Hayes is an Irish-born, London-based writer and director who has, until now, been writing primarily for the screen. Having graduated from Dublin City University with a degree in journalism, she went on to study creative writing at The Irish Writers’ Centre, before finally finding her feet online and honing her craft as a screenwriter through numerous short films and series. Her eight-part thriller, PrankMe, won Series of the Year at SITC, as well as the award for Excellence in Storytelling at Buffer Festival in Toronto. Out of Love is her first novel. When asked why she wanted to make the leap from horror to a love story, Hazel said she could think of nothing more horrific than love.