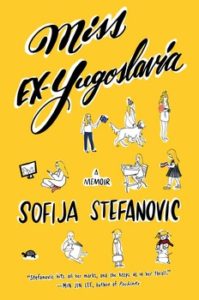

Undercover at the Miss Ex-Yugoslavia Pageant

Sofija Stefanovic on the Weird World of an Australian Beauty Contest

I wouldn’t normally enter a beauty pageant, but this one is special. It’s a battle for the title of Miss Ex-Yugoslavia, beauty queen of a country that no longer exists. It is due to the country being “no more” that our shoddy little contest is happening in Australia, over 8,000 miles from where Yugoslavia once stood. My fellow competitors and I are immigrants and refugees, coming from different sides of the conflict that split Yugoslavia up. It’s a weird idea for a competition—bringing young women from a war-torn country together to be objectified, but in our little diaspora, we’re used to contradictions.

It’s 2005, I’m 22, and I’ve been living in Australia for most of my life. I’m at Joy, an empty Melbourne nightclub that smells of stale smoke and is located above a fruit-and-vegetable market. I open the door to the dressing room, and when my eyes adjust to the fluorescent lights I see that young women are rubbing olive oil on each other’s thighs. Apparently, this is a trick used in “real” competitions, one we’ve hijacked for our amateur version. For weeks, I’ve been preparing myself to stand almost naked in front of everyone I know, and it’s come around quick. As I scan the shiny bodies for my friend Nina, I’m dismayed to see that all the other girls have dead-straight hair, while mine, thanks to an overzealous hairdresser with a curling wand, looks like a wig made of sausages.

“Dođi, lutko” (“Come here, doll”), Nina says as she emerges from the crowd of girls. “Maybe we can straighten it.” She brings her hand up to my hair cautiously, as if petting a startled lamb. Nina is a Bosnian refugee in a miniskirt. As a contestant, she is technically my competitor, but we’ve become close in the rehearsals leading up to the pageant.

Under Nina’s tentative pets, the hair doesn’t give. It’s been sprayed to stay like this, possibly forever. I shift uncomfortably and tug on the hem of my skirt, trying to pull it lower. Just like the hair, it doesn’t budge. In my language, such micro-skirts have earned their own graphic term: dopičnjak, which literally means “to the pussy”—a precise term to distinguish the dopičnjak from its more conservative subgenital cousin, the miniskirt.

Though several of us barely speak our mother tongue, all of us competitors are ex-Yugos, for better or worse; we come from Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. I join a conversation in which go girls yelling over one another in slang-riddled English, recalling munching on the salty peanut snack Smoki when they were little, agreeing that it was “the bomb” and “totally sick,” superior to anything one might find in our adoptive home of Australia.

The idea of a beauty pageant freaks me out, and ex-Yugoslavia as a country is itself an oxymoron—but the combination of the two makes the deliciously weird Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competition the ideal subject for my documentary film class. I feel like a double agent. Yes, I’m part of the ex-Yugo community, but also I’m a cynical, story-hungry, Western-schooled film student, and so I’ve gone undercover among my own people. I know my community is strange, and I want to get top marks for this exclusive glimpse within. Though I’ve been deriding the competition to my film-student friends, rolling my eyes at the ironies, I have to admit that this pageant, and its resurrection of my zombie country, is actually poking at something deep.

If I’m honest with myself, I’m not just a filmmaker seeking a story. This is my community. I want outsiders to see the human face of ex-Yugoslavia, because it’s my face, and the face of these girls. We’re more than news reports about war and ethnic cleansing.

“Who prefers to speak English to the camera?” I ask the room, in English, whipping my sausage-curled head around, as my college classmate Maggie points the camera at the other contestants backstage.

“Me!” most of the girls say in chorus.

“What’s your opinion of ex-Yugoslavia?” I ask Zora, the 17-year-old from Montenegro.

“Um, I don’t know,” she says.

“It’s complicated!” someone else calls out.

As a filmmaker, I want a neat sound-bite, but ex-Yugoslavia is unwieldy. Most of my fellow contestants are confused about the turbulent history of the region, and it’s not easy to explain in a nutshell. At the very least, I want viewers to understand what brought us here: the wars that consumed the 1990s, whose main players were Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina—the three largest republics within the Yugoslav Federation.

“I am quick to tell anyone who asks that I find beauty pageants stupid and that I’m competing for the sake of journalism. However, I am still a human living in the world, and I would like to look hot.”

Like many families, mine left when the wars began, and like the rest of the Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competitors, I was only a kid. Despite the passage of time, being part of an immigrant minority in Australia, speaking Serbian at home, being all too familiar with dopičnjaks, I’m embedded in the ex-Yugoslavian community. Yugoslavia, and its tiny-skirt-wearing prone people, have weighed upon me my whole life.

Most of these young women moved to Australia either as immigrants seeking a better life (like my family, who came from Serbia), or as refugees fleeing the effects of the war (like the Croatian and Bosnian girls).

“Why are you competing for Miss Ex-Yugoslavia?” I prod Zora. “That’s where I come from,” she says, looking down, like I’m a demanding schoolteacher. “And my parents want me to.”

In the student film I’m making, I plan to contextualize the footage of the Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competition with my own story. I’ve put together some home footage of me in Belgrade, before we moved to Australia. The footage shows me aged two, in a blue terry-cloth romper handed down from my cousins. I’m in front of our scruffy building on the Boulevard of Revolution, posing proudly on the hood of my parents’ tiny red Fiat, with my little legs crossed like a glamorous grown-up’s. To accompany these scenes, I’ve inserted voice-over narration, which says, “The Belgrade I left is still my home. I was born there and I plan to die there.” But really, though I like the dramatic way it sounds, I’m not sure it’s true. Would I really go back to that poor, corrupt, dirty place, now that English comes easier to me than Serbian?

I am quick to tell anyone who asks that I find beauty pageants stupid and that I’m competing for the sake of journalism. However, I am still a human living in the world, and I would like to look hot. I’ve had my body waxed, I’ve been taught how to walk down a runway, and I’ve eaten nothing except celery and tuna for weeks, in the desperate hope that it will reduce my cellulite. I’ve replaced my nerdy glasses with contacts, and I’m the fittest I’ve been in my life. A secret, embarrassed little part of me that always wanted to be a princess is fluttering with hope. I’ve reverted to childhood habits of craving attention, and, for a second, I forget all the things I dislike about my appearance. As I observe my fake-tanned, shiny body in the mirror and smile with my whitened teeth, I think, What if somehow, some way, I actually win Miss Ex-Yugoslavia? I allow myself to dream for a moment about being a crowned princess, like the ones in the Disney tapes my dad would get for me on the black market in socialist Yugoslavia.

![]()

This highly amateur competition is the brainchild of a man named Sasha, who organizes social events for the ex-Yugoslavian community. He has managed to gather nine competitors aged 16 to 23 who found out about the event through the ex-Yugo grapevine: a poster at the Montenegrin doctor’s office, an advertisement in the Serbian Voice local newspaper, their parents, chatter in the Yugo clubs where young people go to connect with the community.

Sasha is Serbian, like me. Earlier today, he was bustling around the nightclub with his slicked-back hair and leather jacket, ordering people to set up the runway. I pointed a camera at him and, like a hard-hitting journalist, asked, in our language, why he decided to stage a Miss Ex-Yugoslavia competition.

Sasha turned to the camera with a practiced smile and said, “I’m simply trying to bring these girls together. What happened to Yugoslavia is, unfortunately, a wound that remains in our minds and in our hearts. But now we’re here, on another planet, so let’s treat it that way. Let’s be friends.”

“Do you think we will all get along?” I asked, hoping he’d address the wars he was tiptoeing around.

“I don’t know, but I’m willing to try. I am only interested in business, not in politics.” He looked at the camera to reiterate, to make sure he wasn’t antagonizing any party: “I say that for the record, I am only interested in business and nothing else.”

His interest in business is so keen in fact, that he’s making me give him my footage after tonight. He is planning to make a DVD of the pageant, separate from my documentary. Unlike my film, with which I hope to encapsulate the troubled history of Yugoslavia in under ten minutes, he intends to skip the politics altogether. Instead, he will pair footage of us girls in skimpy outfits with dance music and then sell the DVD back to us and our families for $50.

Now it’s eight o’clock, and the peace Sasha was hoping for reigns in the dressing room. Here, girls help each other with their hair, they attach safety pins to hemlines, and share Band-Aids to stop blisters. The event was supposed to begin an hour ago, but we are still waiting for audience members to be seated. There’s a security guard who is searching each guest with a handheld metal detector downstairs, and I suspect it’s taking so long because all the gold chains are setting it off.

![]()

My camera operator, Maggie, asks me quietly who she should be getting the most footage of, meaning, who’s likely to win this thing? I think it will be Nina from Bosnia. She’s not soft and fresh-faced like Zora from Montenegro, but she is certainly one of the most beautiful competitors. She is very thin, with big eyes, high cheekbones, and a pointed chin. Nina reminds me of the young woman in Disney’s The Little Mermaid who turns out to be Ursula the witch in disguise, which is to say, she’s both attractive and a little dangerous. At rehearsal, she casually mentioned getting into a fight with some girls at a club, to the awe of some of the more straightlaced competitors (myself included). Nina is wise, in many ways more mature than the rest of us, and I’m simultaneously drawn to her and repelled by her. With her gaze that is always calm, almost lethargic, she makes me feel especially neurotic and weird. And she isn’t nervous about going onstage to ogled—she’s got a clear purpose in mind: “Definitely the ticket,” she tells Maggie when asked about her motivation for competing. The winner of Miss Ex-Yugoslavia will receive a ticket back home, to whichever part of that former country she desires, and Nina is itching to visit Sarajevo, which she left ten years ago when it was a bloody mess.

“The horrors of war are generally something people keep to themselves; they are the secrets that wake them up at night, not topics to be discussed on a Friday night out, when turbo-folk music is pumping.”

Partly, it’s my guilt—for not experiencing war firsthand, for having been born in Belgrade instead of Sarajevo—that makes me crave Nina’s affection. My family left not because our lives were in danger, but because my parents wanted their daughters to have opportunities greater than those offered in wartime Yugoslavia. I know that Nina and I share ex-Yugoslavia, but the piece that belongs to her is more damaged than the piece that belongs to me. I wonder if she feels this injustice too, if she has a desire to punish me for the privileges I had, as I, deep down, feel a need to be punished.

“I can talk about being injured by a Serbian bomb if that would be good for the film,” Nina offers, and as Maggie pivots her camera to face her, there’s a knock at the dressing-room door, and Sasha pops his head in. Tina from Slovenia, the only blonde among a sea of brunettes, addresses the camera in English, like an on-the-ground reporter.

“That’s Sasha, the organizer of the event.”

“Just pretend the camera isn’t here,” I say, with a touch of irritation, as I’ve explained this about a thousand times already, and I have a specific vision for this film, namely, for it to look like a fly-on-the-wall masterpiece of observational cinema.

“Are you ladies ready?” Sasha says, in his accented English, staring straight at the camera, confirming that this will not be a fly-on-the-wall masterpiece after all. He clears his throat and continues his down-the-barrel address. “Now, you all know there is only one winner tonight,” he says, and I imagine he’s prepared this speech so that he can include it in his $50 DVD.

“You are all beautiful,” he says with gravity, sweeping across the room with one arm. “But my job is only—for one winner. To. . . give her the crown. He pauses, as if confused by his own clumsy turn of phrase. “That is my job. You have five minutes,” he says solemnly, hurriedly exiting the room and closing the door, as an excited cry rises from the girls, who rush to put the finishing touches on their outfits.

I ask Maggie to follow Sasha and capture some footage of the nightclub filling with hundreds of people. She comes back minutes later, with a worried look. She says she opened the door of the staff bathroom, and interrupted two businessmen snorting cocaine. Those who have seen the mafia portrayed in popular culture would be forgiven for thinking that half the people at Joy tonight are involved in organized crime. And considering how brutal the Yugoslavian wars were, an observer might also wonder—how many of these tall, strong men, in their leather jackets and open-collared shirts, were involved in the violence?

I peek out of the dressing room door to watch the patrons, who have all paid $35 a ticket and are demanding the free glass of champagne they were promised on arrival.

I know that some of the people in this room, all dressed up, smoking cigarettes and knocking back Šljivovica plum brandy, were ethnically cleansed from their villages. When they were fleeing to refugee camps, starving under house arrest, or huddled in basements to avoid bombs, could they have guessed they’d end up here years later, in a club on the other side of the earth surrounded by ex-Yugoslavians from all sides of the war? Yet here they all are, waiting to pick a queen among the young women who will soon be parading their flesh onstage, in a country where bodies are not in danger of being blown up. If they are thinking these things, people aren’t saying them. The horrors of war are generally something people keep to themselves; they are the secrets that wake them up at night, not topics to be discussed on a Friday night out, when turbo-folk music is pumping.

The person who knows these secrets best—what people did to one another in the war—is sitting out there tonight. From my vantage point, I can just make her out, her heavy frame coming into focus through a cloud cigarette smoke. It’s my mother. She’s at a table surrounded by her friends, and every now and then, as if she’s Marlon Brando in The Godfather, someone comes up to her. They’re saying, “My respects, Dr. Koka,” which is what they call her, even though she’s not a doctor. Thanks to my mother’s status as beloved counselor, I am, by default, respected in the community, too.

“Dr. Koka’s older daughter is competing tonight,” people are saying to their friends. I know it already, people are resolved to cheer loudly when I take the stage, out of love for my mother.

I spot another member of my crew, Luke, who I’ve enlisted to record sound. “This is like a Kusturica film,” Luke says with glee, when I wave him over to the dressing room. He’s a fan of the Serbian director who is known for the surreal depictions of ex-Yugoslavians. Luke looks around at my community, clearly hoping a pig will appear and start gnawing at the bar, or that someone will smash a bottle over his own head.

Sasha waves—it’s time. The first stage of the competition, Casual Wear, is in fact just an opportunity to get up onstage wearing a miniskirt and a T-shirt advertising Sasha’s Yugo events business. At the last minute, Nina comes up with the genius idea of tying the front of our T-shirts in a knot, allowing us to show off our midriffs, and at the same time to quietly sabotage Sasha’s attempt to turn us into commercials. We follow her lead. As we rehearsed, we walk single-file out of the dressing room. There is no actual “backstage” area, so the audience can see us as we walk out and stand in line at the side of the stage, waiting to be introduced. Already, it’s embarrassing; as all eyes turn to us, we hear the whooping calls of boyfriends, family, and friends, and the whistles from strangers, while we stare straight ahead.

__________________________________

From Miss Ex-Yugoslavia. Used with permission of Atria Books. Copyright © 2018 by Sofija Stefanovic.

Sofija Stefanovic

Sofija Stefanovic is a Serbian-Australian writer and storyteller based in Manhattan. She hosts the popular literary salon, Women of Letters New York, and This Alien Nation—a monthly celebration of immigration. She’s a regular storyteller with The Moth. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, Guardian.com, and Elle.com, among others. Her memoir, Miss Ex-Yugoslavia, is now out through Atria Books.