Two stories about paranoia for our conspiratorial moment.

Everyone I know is becoming a bit of a conspiracist. It’s hard not to, when the powerful are unrestrained and as unrepentant, and when everything seems corrupted by disturbing associations. There’s less and less subtext, fewer cover-ups. The assholes are in charge. There’s less and less to dig for. What you see is what you get.

So much to say, stories of paranoia don’t carry the same punch as they once did. I rewatched All The Presidents Men last year and found it to be downright quaint. The story of The Washington Post’s risky investigation into the Watergate scandal is the weakest film in the Alan Pakula’s paranoia trilogy. I much prefer the twisted yet lovely romance of Klute, sharp and amazingly performed. But my favorite is The Parallax View, the best film about the JFK assassination by a mile.

A friend invited me to a screening of Parallax at Netflix Presents The Paris Theater, a lovely night at the movies despite the cold and paranoid dread. (A sidebar: really sorry to the guy next to me who I jostled coming back from the bathroom. I was distracted that night and had drunk multiple restaurant carafes of water on top of soup for dinner, which I think we can all agree counts as another large drink. It was a big night, but that’s no excuse to have kneed you like I did.)

Parallax is part of the “too-soon” canon of films that were released not long after the events they’re seeking to understand. Like Godzilla coming out less than a decade after America’s atomic holocaust over Japan, Parallax‘s debut in 1974 was only five years after the RFK and MLK assassinations.

The movie follows Warren Beatty’s Joe Frady, a shaggy and determined investigative reporter, who has gotten too close to a prominent political assassination. Eyewitnesses keep dying mysteriously, and Frady knows there’s more behind it all.

It’s a paranoid classic, a tragic noir for a rickety time. Like all successful paranoid art, the core of the story is unstable. The world and its systems are inscrutable, and attempts to understand are dangerous, and often thwarted. Frady himself is unreliable as a main character. We squint to see him, often caught in wide, distant shots and utter darkness thanks to cinematographer Gordon Willis’ love of shadow.

We’re not alone—Frady is also unable to read himself, and can’t see how his own paranoia and insatiable curiosity makes him the ideal lonely, unwell mark for the shady organization he’s investigating. Those surveilling him see something he can’t see in himself. His paranoia, too self protective and self righteous, alienates him from himself.

In fairness, he’s caught in something too big, too dizzying, too much for one man to wrap his head around. Plus he’s right. The overarching “it goes all the way to the top!” message of the film once struck me as a little on-the-nose, but the elite brazenness has aged into relevance, depressingly. Senators, assassins, and corporations do what they want.

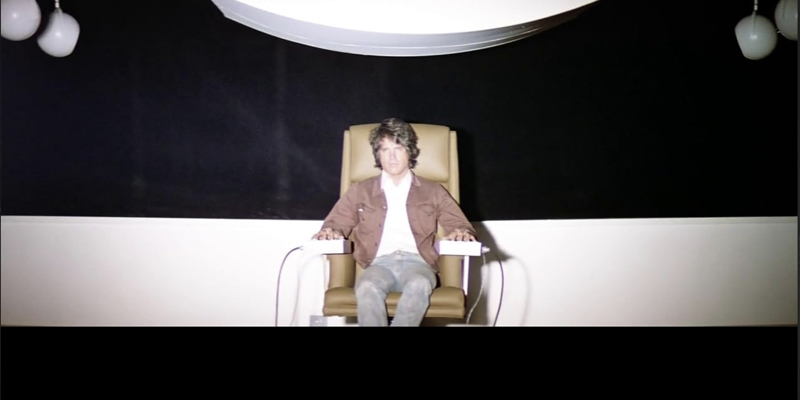

The most memorable sequence in Parallax is its montage. Frady is voluntarily subjected to a disturbing reel of still images and text, juxtaposed and remixed in an overwhelming cacophony of the contradictions and impulses at the heart of America. The state of the nation is unwell. Sexuality, faith, bigotry, and violence are intertwined, reminding me of Pynchon’s image of the Christian fish bumper sticker upended to become a rocket: phallic, destructive, stupidly triumphant.

The sequence is also absurd, surreal, even funny in places. Frady is caught in something confusing and unexpected, his stance of paranoid preparedness unable to outmaneuver this, and what’s coming.

I also just read Ariel Dorfman’s forthcoming novel Konfidenz, another story of paranoia, surveillance, and the indifferent snares of a dangerous world. Konfidenz is set in Paris in 1939, right before war breaks out across the world again, where a woman named Barbara travels to meet a lover. But when he fails to show up as arranged, Barbara finds a waiting car that whisks her to a hotel. And in her room, a ringing phone, and on the other end of the line, a man who knows too much about her. “Konfidenz” translates as confidence, but also trust, and the unknown man on the other end is asking for an extension of understanding.

The book is nominally a spy story, but as a novel is more concerned with identity, exile, and trust. Troublingly, there are unfolding layers of delusion too. Leon, the man on the other end of the line, confesses that he recognizes Barbara as Susanna, a woman who’s been visiting his dreams since he was a boy. What seemed at first like simple transactional espionage is revealed to have a disturbing psychosexual and parasocial dimension.

The paranoia of the exile and the foreigner is also very concerned in language. Konfidenz’s conversations are in German and French, so questions of translation and misunderstanding only heighten the uncertainty and fear. Barbara has no good options, and no good ways to gather enough information to understand her situation. Paranoia is an attempt to reassert control, and Barbara is desperate to feel out the strands of spider silk weaving around her.

Konfidenz unfolds overwhelmingly in dialogue. The internal monologue is perhaps the more obvious choice for paranoid fiction, but by writing in dialogue, Dorfman puts us in the place of the listener with an ear pressed to a closed door, overhearing the anxious voices. This attention to surveillance is always effective in paranoid fiction—The Lives of Others, Jan Procházka’s Ear, and The Conversation come to mind.

But like Pakula’s montage, Dorfman shifts the format of the novel to further unsettle the reader. It’s a startling and effective move, and shifting between first, second, and third person, we are never quite sure who is hatching what plan, who is watching whom, who “you” is, who “I” is. But of course, by the time we have full information it’s too late—the paranoid nightmare.

Paranoia makes the work of trust that much harder, especially when the distrust is validated. It can be more enticing to burrow and fetishize one’s own struggle. Leon tells Barbara that “the worst thing that can happen” is falling in love with your own pain, which means “you end up not having a place in your heart for anybody else’s pain.”

This intimacy has stuck with me. Konfidenz gets at how paranoia, especially the hyper-vigilant attention and the ever-present heat of standing too close to dangerous extremities of action and emotion, can sometime feel, scrambledly, like love. Paranoia’s impulsiveness, fixation, and self consciousness are mirrored in romance as a desire to be perceived in a particular way by a specific audience, a curiosity to uncover something deeper and more vital, and the desire to disappear into a world safe from outside perceptions. An opening to tenderness or vulnerability as a demonstration of trust, versus paranoia’s closing off as an exercise in self protection.

Dorfman writes of Leon feeling “the nearness of her body like an open wound next to my body, so close, the impossibility that it can get any closer.” The echo of the two “body”s, an electric doubling of his physicality in hers.

Both Barbara, and Parallax’s Frady are doomed, entangled in the very nets they feared, so it’s hard to say that their paranoia is wrong. And I relate from here in 2026, where a lot that once seemed delusional has been born out as true. Genocide, conspiracy, and fascism can and will happen here. How do you rebuild any semblance of trust?

Even when it’s the right response, there’s a cost to the stress of vigilance. Alan Pakula’s own life, cut short by a freak, violent accident, is a lesson in the limits of paranoia: you can’t anticipate and outwit everything.

In its worst forms, paranoia is a misapplication of the tools of attention, devotion, and care, scuttled by dread, the oppression of the unknown, and a lack of support. Frady and Barbara end up handcuffed to the demons of their fears, and maybe the way out in an age where our paranoia is validated is to choose our cuffs, to reinforce the solidaritistic bonds with those we can trust. I see paranoia’s obsessive attention in the bright shimmering thread connecting a couple in love, the tenderness between friends in need, the reflexive care for neighbors in the face of danger and violence. It’s always imperfect and never assured, but part of the difficulty of trust is building a comfort with some uncertainty.

I’m reminded of the Auden lines about standing at a window, “As the tears scald and start;/You shall love your crooked neighbour/With your crooked heart.”

James Folta

James Folta is a writer and the managing editor of Points in Case. He co-writes the weekly Newsletter of Humorous Writing. More at www.jamesfolta.com or at jfolta[at]lithub[dot]com.