Two Iconic Russian Poets, the Couch They Shared, and Me

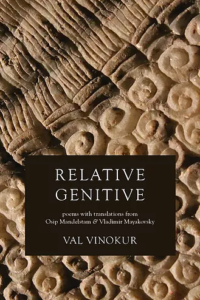

Val Vinokur Writes Poems Between Poems

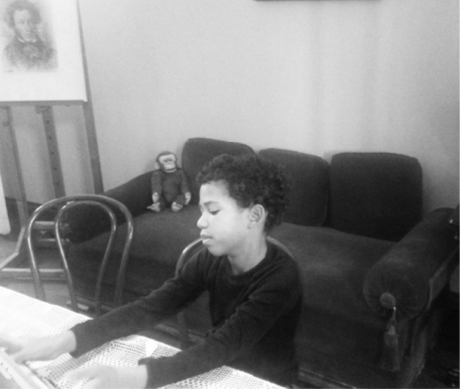

Below is a picture of my son, looking at Anna Akhmatova’s family photo album in her apartment-turned-museum in Petersburg on July 4, 2014. Anna’s stuffed monkey sits behind him on a couch that Vladimir Mayakovsky used whenever he spent the night there, at the Fontanka House. According to the docent, the 6’2” Mayakovsky would have to remove the armrest cushions. Osip Mandelstam also sometimes spent the night on this couch, but did not need to remove the cushions in order to sleep comfortably at Anna Akhmatova’s. His widow, Nadezhda Mandelstam, always objected to descriptions of him as a tiny “homeless bird.” Osia was broad-shouldered, of average height, she would insist.

In the upper left corner, Pushkin gazes down from the same print that inhabited my own childhood home—first in Moscow and later in Miami Beach, packed in our bags when I arrived with my mother and grandmother in 1979. In many Soviet Jewish homes, this image took the place of icons or portraits of Lenin and rabbinic ancestors. If a self-described child of Africa could become the father of Russian literature… So went the beginning of the syllogism that had been rendered opaque in South Florida, which had its own complicated relationship to the descendants of African slaves.

My book is like Akhmatova’s couch. I thought that if both Mayakovsky and Mandelstam could sleep on the same piece of furniture, then my poems could hold the space between my translations of both poets—so radically different in temperament, style, and outlook. Nadezhda Mandelstam describes how her husband became friends with Mayakovsky in Petersburg, but the two separated due to the fact that “it was ‘not done’ for poets of rival schools to associate with each other.” Mayakovsky was a flamboyant Russian extrovert who served the Soviet regime with poster work and poetry until he could no longer muffle his more lyrical energies. Mandelstam was a refined Jewish introvert who poetically defied the regime and was killed by it. In a 1922 article on “Literary Moscow,” Mandelstam writes (in Clarence Brown’s translation):

Mayakovsky is working at the elementary and enormous problem of “poetry for everyone, not for the elite.” Of course, the extending of poetry’s base proceeds at the expense of its intensity, its content, its poetic culture. Wonderfully well-informed about the wealth and complexity of world poetry, Mayakovsky, in establishing his “poetry for everyone” has had to turn his back on whatever was incomprehensible, i.e. whatever presupposed in the listener the slightest education in poetry. But to address, in poetry, an audience totally unprepared for poetry is just as ungrateful a job as sitting on a tack. […] But Mayakovsky writes poetry and very cultured poetry: an elegant song-and-dance man whose stanza breaks up into ponderous antitheses, is saturated with hyperbolic metaphors and sustained in monotonous accentual lines. Mayakovsky has absolutely no business impoverishing himself.

The Acmeist Mandelstam is in many ways a neo-classicist, whereas Mayakovsky is a Futurist, asking in one of his poems: “What’s the point rebuilding Notre Dame?” But in Mandelstam’s poem about that cathedral, it emerges that Notre Dame was never really finished in the first place. “The past has not even been born yet,” he declares in “Word and Culture” (1921). And where Mayakovsky is inspired by the dregs, human and otherwise, of the modern urban streetscape, Mandelstam finds the same when he looks to the late-medieval, Parisian poet-outlaw François Villon. My own work cements all this, provisionally, with the undrying mortar of the high and low: scriptures and television, spirits and dead letters, abject sentiment and exalted wreckage. My poetry moves between introversion and energy, doubt and bravado, and between this world that is supposedly “for everyone” and the obscure ruins of a poetic history—all in an attempt to rescue what can be rescued in both.

Everything is relative and related, genitive and generative. My Haitian wife and I dragged our French-speaking Brooklyn boy to this museum of poets on the Fontanka, but he is the one who dragged me back to Russia because he wanted to meet my father. Our son is our greatest work. This book is a supplement. He already reads me like a book. This is in case he might someday grow curious about the footnotes.

–V. Vinokur

![]()

The golden ray of honey poured out of the bottle

The golden ray of honey poured out of the bottle

So thick and slow, that the lady of the house had time enough to murmur:

—Here, in sad Tauris, where we have been deposited by fate,

We are never bored,—she said and glanced over her shoulder.

The rites of Bacchus everywhere, as though the world were only

Guards and hounds,—you walk around and see no one.

The days peacefully roll by, like heavy barrels.

Far-away voices in a hut—you cannot understand, you cannot respond.

After tea we went out into the great brown garden,

Dark curtains drawn over the windows, like eyelashes.

We walked past white columns to see the vineyard,

Its sleepy hills wet with the glassy air.

I said: Grapevines thrive in this antique battle,

Wild-haired horsemen charging the hills in curly rows.

The science of Hellas among the stones of Tauris,

Highborn golden acres rusting in these furrows.

While in the white room silence spins its wheel,

Smelling of vinegar, paint, wine fresh from the cellar.

Do you remember, at home in Greece, a wife beloved by all—

Not Helen, but the other one—how long she kept on weaving?

Golden fleece, where are you then, golden fleece?

His whole way serenaded by the crash of waves,

Scuttling his ship and its sea-bruised sails,

Odysseus returned, full with time and space.

–Osip Mandelstam, 1917

![]()

AN EXTRAORDINARY ADVENTURE THAT HAPPENED TO VLADIMIR MAYAKOVSKY ONE SUMMER ON A DACHA

Sunset swarmed in a hundred forty suns,

as summer rolled into July;

there was the heat,

the swimming heat—

this all happened in the country.

The slopes of Pushkino, hump-backed

with Akulova Hill,

and below the hill—

there was a village

a crust of crooked roofs.

Beyond the village—

was a hole,

and in that hole, most likely,

the sun sank down each time,

so faithful, slowly.

But once again

tomorrow

to flood the world

the sun would rise up scarlet.

And day by day

this very thing

began

to make me

furious.

And one time so enraged was I

that all things paled in fear,

I shouted at the sun point-blank:

“Get over here!

Stop your loafing in that pitch-hole!

I shouted at the sun:

“Old sponger!

caressed by clouds you are,

while here—winter, summer,

I sit and draw these propaganda posters.”

I shouted at the sun:

“Just you wait!

Listen here, goldenbrow,

instead

of setting aimlessly,

come by,

have tea with me!”

What have I done!

I’m dead!

Coming toward me

of his own good will,

the sun himself,

in wide beaming strides,

strode across the field.

Don’t want to show I’m scared,

I saunter backwards, casual.

His eyes are in the garden now,

in windows,

doors,

through cracks, he came,

piled in, a sunny mass,

poured in;

and with a deep breath,

it spoke in basso:

“I drive the fires back

for the first time since creation.

You called me?

Boil some tea,

poet, spread out some jam, I say!”

Tears in my eyes—

out of my mind from the heat,

but I showed him

to the samovar and said:

“Well then, have a seat, you

luminary!”

Devil made me, raked my arrogance,

to shout at him like that,—

confused,

I sat on a bench corner,

scared—from frying pan to fire!

But, from the sun, a strange radiance

streamed,—

and formalities

forgotten,

I’m sitting, chatting

with the luminary freely.

I talk of this,

of that,

how I’ve been eaten alive by poster-work,

but the sun says:

“All right,

don’t get fired up,

just look at things more simple!

Take me, you think it’s

easy

shining on like this?

Go on and try it!—

You move along the sky—

since move you must,

you move—and shine your goddamn eyeballs out!”

We blabbed like that ‘til it got dark—

‘til what was night once, that is.

For what darkness was there here?

We were familiar with each other,

easy, free.

And soon, since friendship never melts,

I slap him hearty on the back.

And the sun does me the same:

“Me and you, comrade,

quite a pair we make!

Let’s get out there, poet,

let’s dawn

and sing

before this gray mess of a world.

I’ll pour my sunny heart out,

and you—your own,

in verse.”

A wall of shades,

a jail of nights

fell under the double-barreled suns.

A stir of rays and verse—

shine all you’ve got!

And if he gets tired,

and wants a night of rest,

dull sleepyhead,

that’s when I

shine with all my might—

and day rings out again.

Shine all the time,

shine everywhere,

until the plunging end of days,

to shine—

to hell and back!

Here is my motto for you—

my slogan and the sun’s!

–Vladimir Mayakovsky, 1920

![]()

THE GERASIMOVS’

It was not my village:

sugar and egg yolk, liquid sun.

wild strawberries beaded

on a weed thread.

The log farmhouse hundreds

of years old, its timber cut down by axes

after the autumn rain to seal the grain

and left to cure until the spring,

not mine,

the palm-sized fish I caught in the pond

as a boy, my last summer in Russia,

salted and strung on the porch

to dry in the sun, not mine,

not then or now, the toasts to me and to my mother

and my wife and to the children we should have.

The past—near and distant—loses nothing

in the gentle beauty of what is not mine

to lose. Here, memory is born in seconds,

cut down by axes to seal the grain against

the moisture of all that is mine.

Not my village. I the one possessed.

–Val Vinokur

________________________________

From Relative Genitive: Original poems, Translations of Osip Mandelstam and Vladimir Mayakovsky by Val Vinokur. Used with permission of Poets & Traitors Press. Copyright and translation copyright 2019 by Val Vinokur.