Truth and Reconciliation:

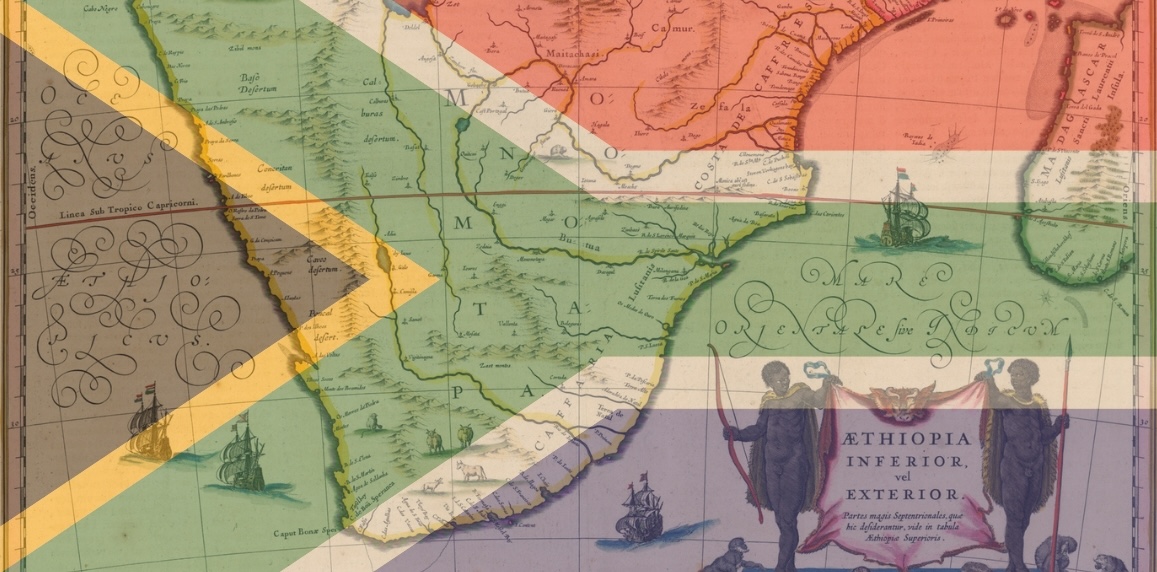

Ten Books That Explore South Africa’s Identity

Lauren Francis-Sharma Recommends Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh, J. M. Coetzee, Mohale Mashigo, and More

In 1996, I lived in South Africa and bore witness to testimony given during the Truth and Reconciliation’s Amnesty Hearings. I was a law student interning at a local law firm and took copious notes during the hearing for a paper I would need to write upon my return home. But even after I submitted the paper, I kept my notes, for I was certain I would never experience anything like that again.

During Covid, I thought a lot about that time in South Africa and after twenty years, I decided to find a way to convey some of what I witnessed. My new novel, Casualties of Truth, set between 1996 and 2018, explores the hearings and its impact on two people.

Much of my reading about South Africa over the years has been overtly political in nature, perhaps because the Republic of South Africa is inherently a country constructed around the political, and yet with this list I wanted to offer a broader glimpse into what makes this fascinating country so unique and so complex.

*

Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh, The New Apartheid

The New Apartheid by Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh, published in 2021, is a critical analysis of “post-Apartheid” South Africa. If you want some reasons for why we haven’t seen as much change as we had hoped after the “Apartheid era,” part of those answers can be found in this book.

Mpofu-Walsh delves into the deficiencies of the South African constitution, often hailed as one of the most progressive in the world, which for example fails to frame “justice” as a fundamental value or address historical dispossession of land.

For sure, there are shortcomings in Mpofu-Walsh’s arguments and the confidence he evokes is that of one who has the clarity of hindsight, but in a dense but passionate text, the young Mpofu-Walsh writes convincingly of the predictable failures of the Black post-Apartheid administration, a body that hoped to build itself on the principles of social justice, yet failed to see how its negotiations in the early 1990s with the white Apartheid government would thwart this goal.

K. Sello Duiker, Thirteen Cents

Thirteen Cents by K. Sello Duiker, published twenty-five years ago, is an intense and devastating novel about an unhoused thirteen-year-old boy in Cape Town. It is grim and violent and perhaps not groundbreaking in its plot, but the story reminds you that Cape Town is a place of deep contradictions.

When you’re visiting, it is easy to focus on the spectacular views and enjoy wonderful meals, but this novel scratches at the veneer of one of the most beautiful places in the world and makes space for the forgotten and overlooked who reside there.

Steve Biko, I Write What I Like

I Write What I Like by Steve Biko who, you probably know, was a young South African activist who grew to fame between the late 1960s and early 1970s. His murder in prison in 1978 at the hands of the South African government was the basis for the movie Cry Freedom, but it was the people’s reaction to his death that galvanized the resistance movement.

Clearly influenced by America’s civil rights movement, I like to think of Biko as the Malcolm X of South Africa, as his goal was not just to physically revolt against oppression, but to alter the minds of Black South Africans.

Beginning with Chapter Four of I Write What I Like, we read Biko’s writings as a student leader, taking aim at white and Black liberals alike, reasserting the tenets of African culture, insisting upon Black consciousness as the true way to establish Black humanity in a society founded upon anti-Blackness.

It’s a riveting and emotional read, and you can clearly see what danger he posed to the Apartheid government.

Alan Paton, Cry, the Beloved Country

Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Paton was published in 1948 and became an instant classic. Perhaps you read it in high school but it was important for me to include it here since it was one of the first novels to achieve global recognition that intended to humanize Black Africans.

Alan Paton writes the story of a Black father and a white father who find themselves embroiled in a crime that shocks the country. The story, written by a white South African born in 1903, is not without flaws, but it gives us a glimpse of South Africa just before the Apartheid-championing National Party wins the election that will change the country forever.

It feels like an honest glimpse of what life is like there before the proverbial walls go up and the story itself is deeply emotional and quite beautiful in the spirit of reconciliation in which it was written. It’s an old standard but worth revisiting with a critical eye and an open mind, and I’m happy I got to write the introduction to Scribner’s 2025 reissue.

Mohale Mashigo, The Yearning

A more recent novel that’s been very popular among young South African women is the debut novel by singer/songwriter Mohale Mashigo, The Yearning. The story delves into ancestral callings and African spirituality and is about a young woman, Marubini, who must find her way after tremendous loss.

It is also about the many ways a family chooses to love. It is not easy finding traditionally published novels by Black South Africans and though this is not a complicated text, it is a wonderful mix of the traditional and the contemporary and offers readers a glimpse into the life of an everyday Black woman in South Africa.

Nelson Mandela, Conversations with Myself

Of course, I could mention Long Walk to Freedom, but I love Nelson Mandela’s Conversations with Myself, as you can really see in these pages how Mandela wrestles with whom he wants to be in the world and to the world. In fact, it’s hard not to note the ways he contradicts himself as we watch him develop into the man we will come to love.

Structurally, it is a bit of an awkward read but ultimately Mandela, the intellectual, the gregarious and earnest man that he was, shines through. Reading his words, as they were spoken or written by him in private letters, always makes me miss his presence in the world.

Joanne Joseph, Children of Sugarcane

Joanne Joseph’s Children of Sugarcane is a beautiful addition to your to-be-read stack. It takes the reader back to colonial India, just as the British were convincing thousands of Indians to travel to South Africa to work in the sugarcane fields.

My first time in South Africa in 1996, I learned that no other country, outside of India, had more Indians per capita than Durban, South Africa. The mix of cultures reminded me of Trinidad, where my parents were raised. Little did I know then that Indians were once enslaved in South Africa and when slavery ended, like in the Caribbean, many more were enticed to leave India in exchange for promises of greater financial opportunities and in some cases, land ownership.

However, the English failed to keep many such promises, and this gorgeously written novel is one portrayal of the struggles Indians faced during this time.

Johnny Steinberg, Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage

Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage is an account of the relationship between one of the most iconic and important Black couples in modern history. Johnny Steinberg risks upending our sanitized version of these two historic figures but somehow understanding them in relation to one another and to their country made me feel less anxious about how the marriage unraveled after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison.

I remember feeling great pain when their divorce was announced, wishing to understand better what happened between them. Steinberg gives us more than a glimpse of what burdens they each had to bear for their country’s liberation.

J. M. Coetzee, Disgrace

South Africa’s, J.M. Coetzee is one of most celebrated writers in the world, and the reasons why seem most clear after reading his novel, Disgrace. I recently reread this novel and still found myself rattled by it. It is a slim, tense, tour de force.

It opens with a professor and an affair with a too-young student, which should be a passé subject, but I dare say it is not. And yet, Coetzee takes it further than a simple fall from academia’s grace. His protagonist, David Lurie is a vile man. He’s a sexist, a racist, a homophobe, clothed as an intellectual, and his worst nightmares come crashing down around him one after the other.

It is a reckoning, for sure, but I can’t always figure out who Coetzee wants to inflict suffering on the most—his readers or his characters, for I have rarely despised and pitied a character more. But it’s the subtext—the way Coetzee manages race, power, privilege and irony (oh the irony!), which leaves me wondering about the author’s intent but also leaves me completely unable to put the book down. It is triggering and brilliant.

Deon Meyer, The Dark Flood

Dark Flood by Deon Meyer is a continuation of a series of books that tell the story of police officer Benny I was gifted my first Deon Meyer novel by a friend while visiting Johannesburg. He told me I was his favorite author “followed closely by Deon Meyer.”

My friend laughed because we both knew the secret truth! Deon Meyer, “gets it right” he told me. Meyer writes of Cape Town with the specificity of someone who has been to every crack and crevice. The descriptions are vivid and the cast of characters, the bad guys and the good guys, of different races and tribes, have the perfect dialectical precision.

It’s a crime novel, so there are guns and chases, but Griessel is a well-developed character with tremendous flaws who somehow happens to always be in the right and in the wrong. Meyer’s books are entertaining and there’s always something new to learn about South Africa in them.

______________________________

Casualties of Truth by Lauren Francis-Sharma is available via Grove.

Lauren Francis-Sharma

Lauren Francis-Sharma is also the author of the critically acclaimed novel ’Til the Well Runs Dry. She resides near Washington, DC with her husband and two children and is the assistant director of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.