Trump Threatened Iranian Cultural Sites. This Is What They Look Like.

Terence Ward on Iran's Stunning UNESCO Heritage Locations

In early January, President Trump astonished the world by tweeting that the United States was preparing to target 52 Iranian locations that would include “sites important to Iran & the Iranian culture.” He brazenly warned Iran’s leaders that he was preparing to commit war crimes and break international law. “We’re not allowed to touch their cultural sites? It doesn’t work that way,” he added a day later.

Surely Trump’s lawyers counseled him the following week about the subtleties of the United Nations’ Geneva Convention that prohibits destroying cultural treasures. But his shocking declaration triggered fears about Iran’s vulnerable historic treasures, some of which pre-date Islam and reach far back into the country’s Zoroastrian past, to a time when Achaemenian Kings ruled the vast Persian empire.

I grew up in Tehran, so I can’t help taking this threat personally. Over the years, I’ve visited many of Iran’s UNESCO heritage sites—ancient and breathtaking—where pivotal cultural flowerings took place millennia before European immigrants first stepped onto America’s shores. Now it’s time to bear witness and recall these monuments before, in a moment of madness, they are destroyed like the majestic Buddhas of Bamiyan.

*

There can be no more poignant place to begin than Persepolis—the royal seat and beating heart of an Iranian empire that stretched at its height from the Indus Valley to the Mediterranean. In the 5th century BC, engineers, architects, and artists from the four corners of the known world were summoned to construct what would serve as a symbol of universal unity and peace.

Set on the plain of Marv Dasht, north of Shiraz, the staggering stage-set has stood for 2,500 years. For each Nowruz celebration, the Persian New Year, that coincides with the Spring Equinox, countless emissaries of the vast Persian empire would gather to give tribute. Offerings from Egypt and India were carried up the dual stairways to the raised platform.

Passing through the Gate of All Nations, the emissaries faced the Apadana Palace built by Darius the Great with its 60-foot soaring columns and a roof framed by cedars of Lebanon.

The imperial city was sacked and burned two centuries later by Alexander the Great (also called “the Cursed” by Iranian chroniclers). Still today, soaring columns and winged centaurs stand guard over the lost throne of Iran and remind visitors that here stood one of the most advanced civilizations on earth. Few settings of antiquity evoke such wonder.

The last time Persepolis was threatened was when Ayatollah Khalkhali drove a column of bulldozers toward the ruins to erase them from the newly formed Islamic Republic in 1979. Instead, the bulldozers were met by furious stone-throwing villagers who drove them back and saved the site.

Five miles away is another site called Naqshe Rustam, where a building rises before a grand panorama of cliff tombs that hold ancient kings. It is called the Kabaa of Zoroaster. Although it may originally have been a royal mausoleum, it reminds us of the crucial role of the Persian prophet in early antiquity. After all, it is from Zoroaster’s faith that early Christians absorbed the idea of the messiah, last judgement, heaven and hell, angels, and even halos.

Further on, in Pasargadae, rests the founding father of the Persian Empire, Cyrus the Great, who freed the Jews from captivity in Babylon, protected freedom of religion, and inscribed the first declaration of human rights in antiquity. His tomb is an exercise in simplicity. Today, it is a pilgrimage site for young Iranians who view him and the pre-Islamic identity of Iran with great pride.

Other ancient sites recognized by UNESCO include the historic city that Marco Polo called “noble Yazd.” Iranians call it “the Pearl of the Desert” and it can be found in the central desert along the ancient silk routes that crossed the Iranian plateau. Thought to be Iran’s oldest continuously inhabited city, it also is the heart of the surviving Zoroastrian community. One can visit their temple, Atash Behram, and gaze at its sacred flame which has remained lit for over a thousand years.

In the fabled city of Shiraz, famed for its poets, roses, and wine grape, rests Iran’s most beloved poet, Hafez. His mausoleum and a tea house are in a garden where Iranian devotees flock, paying homage to his work that transcends politics and speaks freely of love and the celebration of life. Inscribed on his alabaster tomb are the words, “When come don’t forget to bring your wine, and if you spill a drop, I will rise out my tomb dancing.”

The influence of Hafez extends beyond Iran. The poet inspired Goethe’s “East West Divan” and the German author sang his praises: “Hafez has no peer.” Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman also bowed to the poet’s mastery. Even Queen Victoria was said to have consulted Hafez in times of need.

Few know that our word Paradise is rooted in the ancient Persian word pairidaeza or enclosed garden. No wonder that the “Persian Garden” became the metaphor of Paradiso in the Italian Renaissance and was copied by landscape designers the world over. Today, the Garden of Fin, near the city of Kashan, offers a 17th-century Safavid vision of such a refuge. A desert spring gushes forth, filling the fountains, watering the cypresses and roses that also originated in Iran.

There is also the legendary turquoise-domed city of Isfahan and its Naqsh-e Jahan Square, which literally means “Mirror of the World.” This stunning square always leaves viewers gobsmacked. One of world architecture’s most prized sites, it was designed by the visionary Shah Abbas and combines both the secular and the religious, with the Grand Bazaar entrance on one end and the grand Imam Mosque on the other. Seven times the size of Piazza San Marco in Venice, the square hosted polo matches played in front of foreign ambassadors who reclined on the grand terrace of Shah Abbas’s palace.

Across from the Shah’s palace is Sheikh Lotfullah Mosque under its delicate café au lait dome. Upon viewing its luminous interior, the English writer Robert Byron gushed, “I have never encountered splendor of this kind before.” He compared it to “Versailles, or the Doge’s palace, or St. Peter’s. All are rich; but none so rich.”

At the far end of the square rises Shah Mosque, renamed the Imam Mosque in 1980. The magnificent structure arches into a glistening sky-blue dome, with 18 million bricks and nearly half a million aquamarine and canary-yellow tiles. The design is so daring that its only earthly rival is Brunelleschi’s terra-cotta Duomo in Florence. A zenith of Islamic architecture, the Imam Mosque is the very symbol of Isfahan’s 17th-century renaissance, and staggers all viewers with its grandeur.

Of the monuments found across the vast country, I have only mentioned a few. Yet, coincidentally, Iran and the US share exactly the same number of UNESCO cultural heritage sites—34. During the Iraq-Iran war, Saddam Hussein tried to bomb these treasures, knowing he would strike at Iranians’ hearts. How ironic that President Trump would threaten to follow Saddam’s example and do the same.

__________________________________

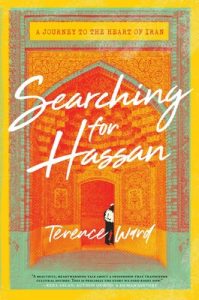

Terence Ward’s Searching for Hassan is out now from Tiller Press.