Truman Capote, Bennett Cerf, and the Making of In Cold Blood

Gayle Feldman on How Random House Brought Capote’s Magnum Opus to Bookshelves Across America

Bennett Cerf’s decision to sell Random House to the Radio Corporation of America early in 1966 opened a door to the unknown, but his days stayed grounded in the work he knew and loved. His diaries were full of Philip Roth, John O’Hara, Ted Seuss Geisel, James Michener, and William Styron, but no author was more present than Truman Capote, whose latest book, In Cold Blood, was published a week after the RCA agreement was announced.

More than six years had passed since Capote, looking for a quick non-fiction project to earn some cash, had run across a wire-service story from Kansas while scanning the back pages of The New York Times. Dated November 16, 1959, the piece was headlined “Wealthy Farmer, 3 of Family Slain.” He read that forty-eight-year-old Herbert W. Clutter, owner of a thousand acres, along with his wife and teenage son and daughter, had been bound, gagged, and killed at close range by shotgun blasts in their isolated farmhouse outside the town of Holcomb. The phone lines had been cut, yet nothing had been stolen. Two of the daughter’s classmates had discovered the grisly mayhem; at the time of writing, no suspect had been identified.

Capote got the go-ahead from The New Yorker’s editor, William Shawn, to delineate the effects the murders were having on the small Kansas community. He’d have to travel to the flat, chilly prairie, sniff around, and absorb a place that was as alien to him as any he’d known during his sojourns abroad. Although at that time he didn’t expect the article to stretch to book length, Capote hurried to tell Bennett, for he needed his help: he knew not a soul in Kansas, and Shawn, an extremely shy man, had no connections. On the other hand, “Big Daddy,” as Truman teasingly liked to call his book publisher, had friends all over.

Where Capote diverged was in wanting to create a nonfiction narrative that in attention to style, character, atmosphere, voice, and pacing would display all the hallmarks of the finest fiction, while hewing to the facts.

“You? In a west Kansas hamlet?” Bennett had chuckled, but then turned serious: Truman could count on his help. On a lecture trip five years earlier, he’d visited Kansas State College, where in addition to his official talk, he’d spent a day with English classes. As a celebrity, he’d also met the school’s president, James McCain, and liked him well enough to give the college a nod in his “Trade Winds” column in Saturday Review. McCain had told him to get in touch if he could be of service. Now he picked up the phone to renew the connection, and was in luck. McCain had known the Clutters, and was familiar with leading citizens of Garden City, the nearest big town to Holcomb. He’d write letters of introduction and make calls, but in return wanted Capote for an evening with the English department. New York writers didn’t turn up in Manhattan (Kansas) every week.

Bennett accepted the invitation for Truman and, when McCain said that he and his family would be visiting New York that Christmas, hastened to invite them to lunch at ‘21.’ It would be a thank-you, but also a chance to hear a firsthand report on Truman’s activities, for beneath their lighthearted banter lay real affection between the older man and the “strange little boy” who’d grown up at Random. At times Bennett worried about him, and took it upon himself to prepare McCain—so McCain could prepare others—for the meeting. When people met Capote, Bennett admitted, they often were inclined “to laugh,” but “don’t let that first impression fool you.”

Nonetheless, even armed with McCain’s goodwill, Capote was well aware that a tense rural hamlet reeling from multiple murders might not take kindly to a high-pitched elfin outsider, looking much younger than his thirty-five years, nosing around. He wanted a friend with him to provide fellowship and help with legwork, so as not to linger long. The timing proved perfect for his childhood soulmate Nelle Harper Lee, who was delighted to play detective beside him: the adventure would distract from the itchy limbo of waiting for publication of her own novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, the next summer. Almost three years earlier, she’d had a chance to bring her writing to Random House; Capote had spoken to editor Albert Erskine about her, and Erskine had asked to see Lee’s work. She’d just given a few stories to a literary agent, soon followed by the first fifty pages of a novel. However, she told Erskine that what she had was already “in the market,” politely rebuffing his approach; the agent had sent the pages to Lippincott. Bennett—who later judged Mockingbird one of the finest novels in recent years—was convinced Lee thought RH would take it “just to please Truman,” and wanted “to make it on her own.” But aiding Capote with his work was different. She was sorely needed: when they arrived the second week in December, first sightings of Capote raised eyebrows and suspicions.

McCain described to Bennett how Truman had waltzed in sporting pink velvet, saying, “I bet I’m the first man…to come to Manhattan, Kansas wearing a Dior jacket.”

“I’ll go you one better,” he’d replied drily. “You’re the first man or woman who ever came to Manhattan, Kansas, wearing a Dior jacket.”

With Lee’s help, Capote worked to tamp down misgivings. Alvin Dewey, the detective in charge for the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, began to tolerate him; later, Capote would charm Dewey’s wife, Marie, and Dewey himself. With a bit more time, he’d morph into an “attraction” whose fascinating conversation opened doors to almost all the best homes.

On December 30, two suspects, Dick Hickock and Perry Smith, were seized in Las Vegas. They confessed, and Dewey brought them back to Kansas. Now Capote knew he had more than a New Yorker article facing him: he had the full tragic arc of a book. Although other detectives were also involved, he’d found a hero in handsome Al Dewey, and villains in the two men. He’d delve deep into what had formed them and motivated the killings, and what fate had in store, with his original plan of anatomizing the victims and their community layered beneath. In a sense, he’d be treading a time-honored path: novelists like Balzac and Dreiser had mined newspaper accounts as starting-off points. Where Capote diverged was in wanting to create a nonfiction narrative that in attention to style, character, atmosphere, voice, and pacing would display all the hallmarks of the finest fiction, while hewing to the facts. This was something new. Immensely excited, he quickly signed a contract with Bennett, and was soon visiting the killers in jail day after day, determined to win their trust, and stare into their very souls.

Dick Hickock was fair and twenty-eight, Perry Smith dark and thirty-one—close in age to their chronicler. While Capote’s lack of height and high voice made him stand apart, something was physically “off ” about each killer, too. Hickock had been in a car accident that left his eyes uneven and face a bit askew; having grown up poor on a small farm, he’d been twice divorced, committed crimes seeking easy money, and was mean, with a cruel streak, and knew it. Smith’s face, with the smoke-black eyes and hair of his Cherokee mother, seemed to beg for sympathy. A motorbike crash had so damaged his legs, he was almost as short as Capote, but what truly set him apart were the dark sights behind his eyes: a neglectful, alcoholic mother who’d died young, a father who’d abandoned the family, a childhood of awful brutality in orphanages and “homes.” Smith saw himself as kind, sensitive, well-meaning, highly intelligent, and fantasized about the life he might have led. Devoted to self-help books and word lists, he used fancy vocabulary to seem superior and worldly-wise. He’d killed two Clutters by his own admission, though Hickock said it was Smith who’d dispatched them all, and Capote would later agree. However, Smith mesmerized Capote, and in a deeply terrifying way. In him, Capote could recognize so much.

Truman’s birth father, Arch Persons, was a con man who’d abandoned him during much of his childhood; his mother, Lillie Mae Faulk-turned-Nina Capote with her second marriage, was a narcissistic alcoholic who ultimately killed herself. Truman had been shunted off to relatives and marked as an outsider from the beginning. But where Smith believed unrealistically in talismanic lists and self-help books to redirect his life, Capote clung fiercely to his own brilliance and hard work.

Home from Kansas in late January 1960, he saw a lot of Bennett. In March, he and Lee returned to observe a quick, weeklong trial in which the outcome was obvious. Found guilty, Smith and Hickock were sentenced to hang on May 13, but Capote had no intention of making another pilgrimage to witness that. Once again back in New York, he intimated that the writing wouldn’t take long—at least, that was Bennett’s impression. Capote was returning to Europe to escape the social whirl, hunker down, and work. At the spring sales conference, Bennett couldn’t help telling the reps about the book. Their “tongues [were] hanging out” and “pencils poised” to take orders, he wrote Truman, but it would be far longer than either imagined before they could do so: Smith and Hickock appealed the convictions, and the gears of justice turned with their own sense of time.

As Capote worked across the Atlantic, Bennett stayed in touch. Random House had just made an initial public offering, and the Cerfs delightedly sent him a Christmas gift of five shares. Bennett knew enough not to press about the book. However, when Ernest Hemingway died in July 1961, prompting scrutiny of the American literary pecking order, he figured that Capote, three thousand miles away, would wonder about his place in it. Truman had been abroad almost a year and a half, and to assuage his own worry about progress, Bennett reminded him “how very, very much we miss you,” adding: “Bill Styron listed you as one of the really important writers…today.” Only then did he mention the book, admitting impatience, but knowing Capote would finish “when it satisfies the incredibly high standard you have set and maintained for yourself.” But however delicately he’d finessed the reminder, a few months later, a “terribly upset” Truman cabled, demanding to know if Random House intended to publish another Clutter book, by a certain “Mack Nations.”

Bennett replied instantly that of course he’d “never do anything” like that, mystified where the devil Truman had picked up such an idea. But the Nations project, it turned out, did exist. A politically connected small-town Kansas reporter, Nations had interviewed Dick Hickock and several other inmates for a story on death row. While Capote was abroad, Hickock had decided that if anyone were to profit from a book about his life, he should. He signed a contract with a fifty-fifty split between himself and Nations, who interviewed him and that December placed an “abridgement” of his manuscript in Male, a pulpy adventure magazine.

Capote was so anxious, he’d confided to the Deweys that the strain of the book made him sick to his stomach every morning. Soon, however, Bennett was the one seeking reassurance. A rumor that Capote was dallying with an offer from McGraw-Hill for more money began to circulate. When repeated to the Cerfs at a dinner party, Phyllis exploded: “Truman Capote is going to be with Random House as long as he, Bennett and I are alive, and whoever told you that story is a goddam liar!”

Real comfort came a couple months later in Truman himself, who returned to New York briefly en route to Kansas, where he’d interview Smith’s sister, and meet with the killers on death row. He’d heard they might be granted a new trial because of a ghastly legal mix-up, and was despondent about a delay. He stayed with the Cerfs for five days, secure in their affection and a sweetness he could tap into in Bennett. Years later, he’d tell his biographer how he could really talk to his publisher, who underneath the vast public surface was an “extremely sensitive” man. When they were together, Bennett was the listener. But in other ways, the visit proved hard. Capote felt alienated from friends clamoring to see him, who pressed in, expecting to be entertained by the antic butterfly they knew. Instead, he felt trapped in a bleak place so vivid, he was horrified by his dreams. Swallowed up by a relentless writing routine and his own perfectionism, In Cold Blood was all he could think of. He wanted to be rid of the goddamned book, but the only way was by writing the goddamned book. It had become his life.

He’d brought a precious gift to the Cerfs: two hundred manuscript pages. Only Bennett and The New Yorker’s Shawn were permitted to read them, and Bennett was overwhelmed by “how very much” Capote had grown as a writer. Wanting to share his feelings with someone who’d understand, he wrote to Jim McCain that In Cold Blood was destined to be “one of the greatest” American books this half century, and later reiterated to the British publisher Jamie Hamilton that it was “one of the most important” either firm “ever had the privilege” to print.

In Cold Blood was all he could think of. He wanted to be rid of the goddamned book, but the only way was by writing the goddamned book. It had become his life.

Capote returned to Europe, but despite the faith and encouragement from Bennett, he felt even worse, his emotions conflicted and churning. He’d grown dangerously fond of Smith, identifying far too closely with his dark doppelgänger. Moreover, he knew both men were counting on him to help them evade the noose. He’d tried to help, suggesting lawyers and so forth, but had also needed them to talk, so how could he discourage their fantasies? He’d told Bennett that he required at least another year to complete the book, but understood rather too clearly that the final chapter could be written only after there was a hanging.

Four years had passed since Breakfast at Tiffany’s was published. To keep Capote’s name in front of readers, Bennett thought it wise to assemble a collection from earlier material that had never appeared in a book. Truman would help choose the pieces: the distraction might do him good. When Selected Writings was published in 1963, it bore a dedication to Phyllis and Bennett. The volume was eventually reprinted in the Modern Library—an accolade that greatly pleased its author. He finished the third part of In Cold Blood in February 1963 and kept working, but anxiety gripped him with word that Hickock and Smith had appealed in federal court for a new trial. If they got it, he feared he’d have a breakdown; already, he was drinking more. Finally, on February 20, 1965, more than five years after setting foot in Holcomb, he wrote Bennett, “Yesterday I finished…except for a few paragraphs,” and said he would mail the manuscript to his Random House editor, Joe Fox.

The court denied the latest appeal, but the lawyers got another stay of execution. Still, Capote felt sure that the killers’ luck had run out. Back in March 1960, when they’d first been condemned, he hadn’t felt a need to be present at the execution. Now his life had become too bound up in theirs. They each had the right to ask for a witness, and wanted him. Having become so entangled, he knew he had to finish by seeing them hang. He couldn’t go alone. The circumstances made the role ill-suited to Bennett, and everyone knew that Shawn was beset by phobias. However, Bennett would not fail him: someone else at Random would go. Like Saxe Commins, Random House’s first great editor, when he was summoned to cope with Bill Faulkner in the throes of his worst kind of alcoholic binge, Joe Fox, as editor, would look after Capote. The two men were polar opposites, but Fox knew how to talk to him.

They arrived in Kansas City and holed up in the Muehlebach Hotel. Fox had to field repeated calls from the prison’s assistant warden, phoning on behalf of Smith and Hickock, who desperately wanted to talk to Capote. He just couldn’t. Nor could he sleep or leave the room; he sat and cried. He’d come all this way, but wasn’t sure he could make it to the hanging. However, in a cold spring rain very late on April 13, he and Fox joined three Kansas detectives and headed for the prison, a half hour away. He and the detectives went in to see the condemned. Time passed, he reappeared, and motioned for Fox to follow, then introduced him to Hickock and Smith: awkward, thoughtless, but also understandable. He had no idea what he was doing. It was after midnight when the men were transferred to a warehouse where the gallows waited. Fox stayed outside, but Capote saw Dick Hickock hang. When it was Perry Smith’s turn, he couldn’t watch.

Sometime before boarding a plane in Kansas City, they called Bennett. Capote sobbed on the flight back to New York, tightly clutching Fox’s hand. It was a long journey and felt longer still: the weeping did not stop. All Fox could do was cradle Truman’s hand, stare straight ahead, summon a proud mournful dignity, and try to pretend that the people all around them did not exist.

________________________

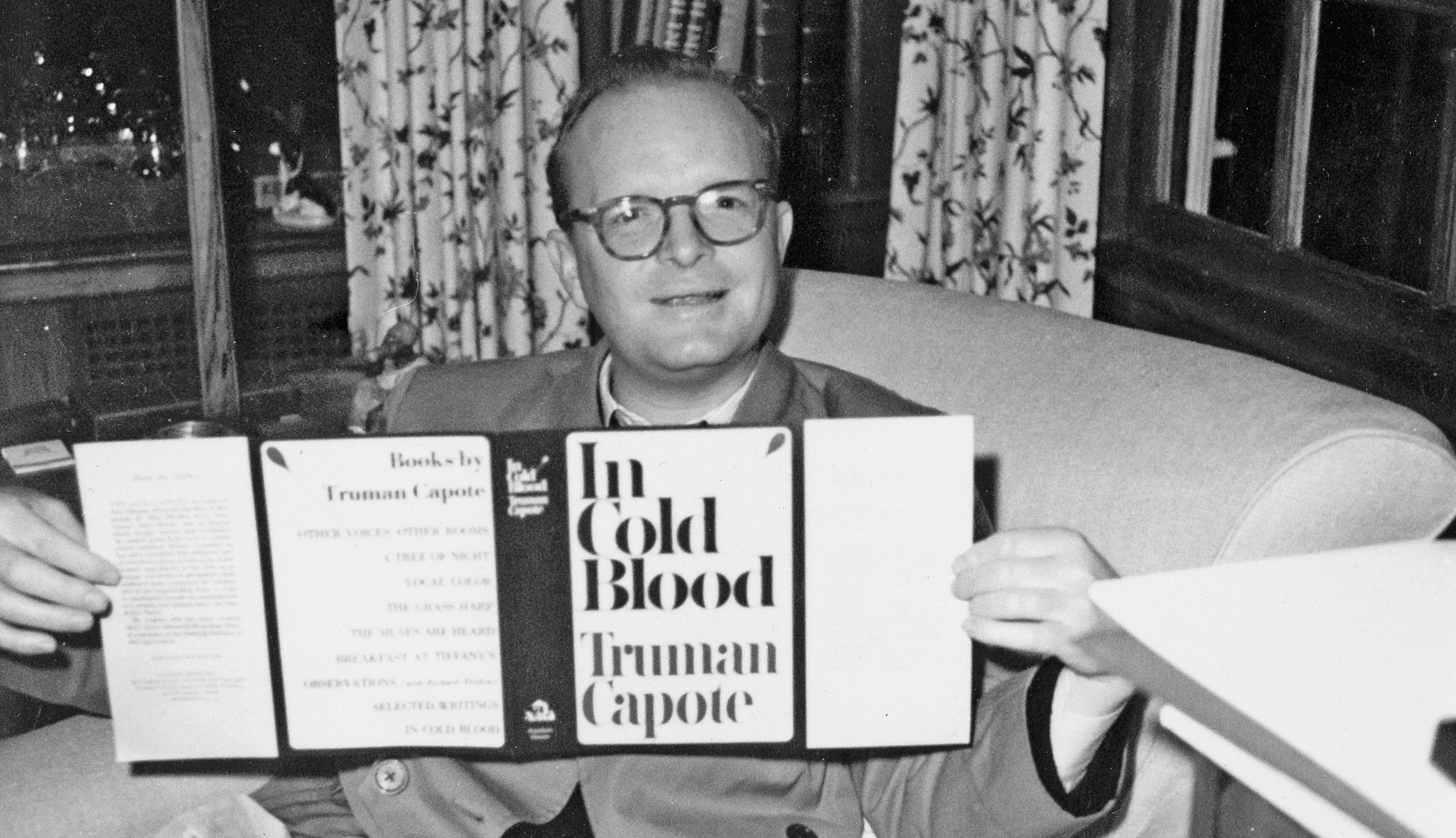

Excerpted from Nothing Random: Bennett Cerf and the Publishing House He Built by Gayle Feldman. Copyright © 2026. Forthcoming in January 2026 from Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Feature photo of Truman Capote with book jacket by Phyllis Cerf, courtesy Christopher and Jonathan Cerf.

Gayle Feldman

Gayle Feldman has written for Publishers Weekly for forty years, including as a senior staff editor. Since 1999, as U.S. correspondent for The Bookseller, she has analyzed the American book business for U.K. readers. She has also contributed features, reviews, and essays to The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Times of London, The Nation, The Daily Beast, and other publications. She is the author of the cancer memoir You Don’t Have to Be Your Mother, first published by W. W. Norton, and was awarded a National Arts Journalism Program fellowship at Columbia University, through which she published Best and Worst of Times: The Changing Business of Trade Books. The National Endowment for the Humanities has supported her work on Nothing Random with a Public Scholar award. Feldman lives in New York City.