Triumph and Tragedy: On Being a Mets Fan... and Being a Mankiewicz

Nick Davis on His Renowned Family and the Mysteries That Still Remain

Being a fan of a sports team is a lot like being a member of a family.

You love them, you hate them, but you can’t escape them.

In my case, I have no memory of life before I was a Mets fan, and no memory of not being a Mankiewicz.

That is about the only sense I can make of the bizarre coincidence of two projects I have poured heart and soul into—one about the New York Mets, the other about my family—being released into the world on the exact same day this month.

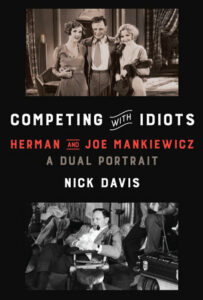

(On September 14, the first two parts of a four-hour documentary series I produced and directed about the 1986 Mets, Once Upon a Time in Queens, will air on ESPN’s 30 for 30 series. That same day, a book I have written about my maternal grandfather and his brother, Competing With Idiots: Herman and Joe Mankiewicz, a Dual Portrait, will be published by Knopf.)

The 1986 Mets were one of the most charismatic and talented sports teams of all time, a comet that blazed across the city and won a thrilling and miraculous World Series. As for the Mankiewicz brothers, Herman and Joe, born nearly 12 years apart, were responsible for some of the greatest films in Hollywood’s golden age (my grandfather cowrote Citizen Kane with Orson Welles, and Joe wrote and directed All About Eve, among others).

What the heck do these two things have to do with each other? Really, what does Keith Hernandez have to do with Herman Mankiewicz? For that matter, does anything unite Darryl Strawberry with Addison DeWitt?

The Mankiewicz brothers, Herman and Joe, born nearly 12 years apart, were responsible for some of the greatest films in Hollywood’s golden age.

The key to the coincidence may be something that lies at the heart of both sports and families: loss. Our families and our sports teams provide moments of what can only be called trauma—try telling a 12-year-old boy that June 15, 1977, when the Mets traded Tom Seaver, wasn’t a historical disaster on the order of December 7, 1941. In fact, that date is the germination of the 1986 Mets tale: the disastrous trade ripped the heart out of the franchise and the city. In the “Ford to City: Drop Dead” 1970s, the Mets’ subsequent mediocrity, combined with the reign of the Reggie Jackson Yankees, brought the team to the utter depths. For the team and the city, there was nowhere to go but up . . . the miraculous and serendipitous building of the team (which coincided with the apparent clean-up of New York and the booming Wall Street of the yuppified 1980s)—the coming of the prodigies Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden, the trades for the veteran leaders Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter . . . none of it would have happened without the nadir of June 15, 1977.

No Seaver trade, no 1986 Mets.

Tragedy and trauma, too, lie at the heart of my family’s story. Though my great Uncle Joe lived less than an hour away from our home in Greenwich Village, we almost never saw him when I was growing up. Joe had been like a second father to my mother, as Herman had died when she was 15. That my mom herself died in a freakish car accident when I was only nine meant I was never able to ask her about her uncle, or why we never saw him.

It was only years later when I met Joe as an adult—and found him warm, witty, and self-deprecatingly wise—that I started to investigate, and found only more tragedy, more trauma: Joe’s second wife Rosa committed suicide in 1958. She had been in and out of sanatoriums for more than a decade, and her death wasn’t entirely a surprise. But Joe’s behavior the day her body was discovered was—he had spent the previous night in New York City, while Rosa was at their second home in Mt. Kisco. Unable to reach her on the telephone that day, rather than driving up from the city to check on her, or call a friend to do so, he enlisted the help of his 20-year-old niece, my mother.

The two of them drove up from the city to check on her together. When they arrived at the house, Joe stayed downstairs, and he sent my mother upstairs to the master bedroom, where she discovered the body of her dead Aunt.

Joe’s behavior that afternoon sent shock waves through the family that continue to the present day. Why did he ask his niece to accompany him in the first place, and then to check the bedroom? Was he really ignorant of what she might find up there? My mother came to feel set up, that Joe had known all day that Rosa was dead, and that Joe was merely casting her in some movie in his imagination, so that he could play the role of the comforting uncle afterwards, patting her hair and trying to soothe her from what she described years later as the shock of a lifetime.

I have no memory of life before I was a Mets fan, and no memory of not being a Mankiewicz.

What drives a man to such extreme behavior? Is it possible that his fiercely competitive relationship with his older brother Herman was the cause of his actions that afternoon? Herman, after all, had been a beloved, legendary figure in Hollywood (the subject of David Fincher’s Mank), and one of the greatest screenwriters of Hollywood’s golden age, though he drank himself into an early grave, scattering one-liners like chicken feed while he worked on movie projects which, with the possible exception of Citizen Kane, he felt were obviously beneath him.

So was Joe trying to hurt his brother’s child that afternoon? Was he still competing with the Herman in his back row of his imagination, the man who had regularly derided him as his “idiot brother”?

Or did Joe’s behavior have nothing at all to do with Herman that afternoon? Was he innocent of anything but the need to have some human connection during a stressful afternoon? Did my mother overreact?

My Mom’s early death only deepened the mystery.

So the great dividing line of my life—July 25, 1974, when my Mom was out walking in Greenwich Village and two taxis collided, one spun around, and ended her life—was also the inciting incident of my book. Had she lived, she would have told me the truth, or her version of it. Had she lived, I would never have felt drawn to these two men, as if perhaps by unlocking the secrets of their relationship I could reclaim some small part of my mother.

No death of Mom, no book about her father and uncle.

So there we are, the two pillars of trauma that defined my childhood: the loss of my Mom, the Tom Seaver trade.

All is not perfect, no one wins all the time. Life is about suffering, and pain.

Surely that is the credo of the Mets fan anyway, a franchise suffused with suffering and loss. (Consider the title of Devon Gordon’s excellent new book So Many Ways to Lose.) The 1986 Mets were the glorious exception. Nearly everything else in the team’s history has ended badly.

So it is with families—not just mine, but all families. To be a member of any family is to have relationships with people who, no matter what, will one day no longer be there. Loss. Pain. Suffering. We can triumph, for sure—Mookie can dribble that ball down the line, Herman can summon all the brilliance at his disposal and return from Victorville with the script of a lifetime—but nothing lasts forever.

_______________________________________

Competing With Idiots by Nick Davis is available now from Knopf.

Nick Davis

Nick Davis is a writer, director, and producer. He lives in New York City.