Translating the Magical Imperfection of Oral Tradition to the Page

Vaishnavi Patel on Finding Inspiration from the Ramayana

Every summer as a kid I would wait anxiously for lunchtime. It wasn’t just because we got hot, fresh Indian food, although the ghee dripping off the roti certainly helped. It was because my Ajji (grandma, in Marathi) lived with us in the summer, which meant lunch was story time. Once my sister and I were situated at the table, Ajji would take requests. We would request myths in one breath, and family stories in the next—tell us how Hanuman lifted the mountain! Tell us how our aunt fell in the fountain! Tell us a new one!

After a bit of consideration, Ajji would pick a story. Sometimes it would be what we requested, but sometimes it would be something we had never heard, or an old story that she felt like telling. It was from Ajji that I first heard the Ramayana, told in pieces and out of order. We would hear the climactic battle one day, and the kidnapping of Sita (one of the inciting events) the next.

Over the course of a summer, interspersed with unrelated stories and dialogues with my Aai (mother), we reached the homecoming at the end of the Ramayana. Even today, the Ramayana is inextricably linked to my Ajji and our foray into the world of oral tradition.

Oral tradition is possibly the oldest form of generational communication in existence, and continues to be one of the most common, despite the rise of the written medium. For thousands of years, even after the invention of writing, a majority of the world’s population was only able to access the oral medium. South Asia has a strong and vibrant oral tradition that persists today, used to pass down religion and myth as well as family history.

The Ramayana itself began as a story told via oral tradition, which scholars believe predates its first written version by almost one thousand years. And the written Ramayana is full of references to the story’s roots, where characters will pause to narrate other related stories, or sages will have a colloquy about the story within the story.

When my Ajji told us stories over lunch, we were all participating in that millennia-long transmission of one of India’s oldest stories. Oral tradition is a deeply interactive and participatory process—it leaves room for clarification, for dialogue, for question and answer, for modification with each telling. My sister and I would often interrupt, or fill in the blanks, asking questions or predicting twists, and my Ajji would alter her storytelling to tell us more about what we were enjoying—playing up the comedy or the pathos or giving us a tidbit about a favorite side character.

Our stories weren’t only cabined to lunchtime, nor were they confined to telling religious or other third-person stories. Family histories are also often passed down orally in a variety of cultures, and my family was no different. Any statement or question to my Aai or Ajji could trigger a ten-minute-long story about their own childhood, or their parents’ lives. As a child it was annoying—I didn’t want a tangent!—but I am now able to appreciate how much I learned about my own history in these tidbits, and how often these anecdotes actually gave me the advice I needed to navigate my own problems.

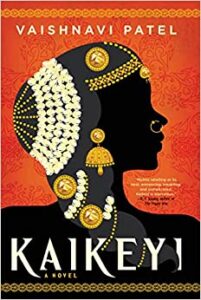

I loved interacting with stories, pushing and testing their boundaries, and I wasn’t the only one. Once, my Aai overheard my Ajji telling us about Kaikeyi’s role in the Ramayana and jumped in to explain how Kaikeyi was misunderstood. This minor disagreement, made possible by our daily storytelling ritual, planted the seeds that eventually became my novel Kaikeyi.

Though I have since read the translated original epic as well as other written versions, I knew, in writing Kaikeyi, that I needed to honor these oral roots, both of the epic itself and my own personal relationship to it. The world of Kaikeyi is a composite of ancient South Asia before 0 BCE, a broad time horizon in which oral tradition would have been the main mode of storytelling, especially for women.

Outside of the western canon (and sometimes even within it), stories are still shaped by oral storytelling, and the collaborative process of telling and retelling stories.

One of the character Kaikeyi’s main means of access to oral tradition is through Manthara, her nursemaid and stand-in mother figure. Although not discussed on the page, Manthara is likely illiterate, but she knows the myths of her world because of oral tradition. In passing them on to Kaikeyi, especially when Kaikeyi is a child, she participates in the generational transfer of knowledge—here, religious knowledge—that sets oral tradition apart from oral communication alone.

In trying to put oral tradition into a written format, I knew I would necessarily lose some of what makes oral tradition so magical—the spontaneity of interaction, of what comes next not being already written. So while sometimes we hear Manthara telling Kaikeyi stories, I also depicted Kaikeyi remembering the stories to herself, retelling what she took away from the story and preserving her memory of the wonder of those narratives. This allowed Kaikeyi to participate in the continued recollection and preservation of stories—another vital part of the oral tradition process. I also included instances of family histories being passed down, sparked by questions or other triggers, because even in this story I wanted oral tradition to feel deeply personal, integrated into the fabric of the world.

Beyond my enjoyment of hearing stories passed down through oral tradition and my nostalgia for this important part of my own childhood, oral tradition is a vital cultural force that allows stories to spread and take on flexible meanings to speak to different groups of people. That is not to say written work cannot have this complexity, but oral tradition lends itself to having many versions coexisting at the same time.

The Ramayana itself is an example of the ease with which multiple versions of one story can exist and spread—there are hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of versions of the Ramayana, many existing only as stories passed down orally. But the Ramayana also illustrates the danger of holding up one narrative as supreme, because increasingly, one version of the Ramayana, based on the written Valmiki Ramayana, has become the accepted “norm” and alternative versions are spurned as inaccurate.

There is a story, repeated as a motif throughout Kaikeyi, which Kaikeyi first reads as a young girl. As she retells the story to herself, it changes, taking on a special meaning to her because of her own experiences. Later in the book, Kaikeyi finally discusses the story with someone else. But that person has their own version of the story, and tells Kaikeyi her interpretation, forever altering Kaikeyi’s view of the world she thought she knew. And although a written book, I like to think Kaikeyi itself participates in this tradition.

Kaikeyi is a highly maligned character in the traditional Ramayana, ruled by her emotions and jealousy, entering the story to play one primary antagonistic role and then departing. In Kaikeyi, she is a fully realized character, shaped by her life experiences to make decisions that don’t simply boil down to “evil stepmother.” Kaikeyi presents an alternate version of the Ramayana, a branch not taken that was made possible by oral tradition and its many Ramayanas.

Kaikeyi wouldn’t exist without oral tradition. Outside of the western canon (and sometimes even within it), stories are still shaped by oral storytelling, and the collaborative process of telling and retelling stories. While oral tradition may feel like an unfamiliar device, or perhaps an archaic one, kids today continue to grow up in these traditions. Many of my South Asian friends heard stories at their dinner tables, and I know children all over the world share in this experience. Including it in Kaikeyi is a way to honor this beautiful part of my culture.

Oral tradition is imperfect, as all human knowledge is, and it is certainly harder to transmit any single instance of it to a wider audience. But it is not lesser then the written medium—it is adaptable and beautiful and full of wonder. There’s something about knowing that the words came from my Ajji, were chosen just for us and just for that moment, that made hearing her stories all the more precious. When she spoke, it was not just with her voice, but her mother’s voice who told my Ajji these stories, and her mother’s mother, and on for generations. Oral tradition meant that I heard a collective story, and that act of hearing made it mine too. In putting those stories in Kaikeyi, I hope I have made the story ours.

_______________________________________

Vaishnavi Patel’s Kaikeyi: A Novel is available now via Redhook.

Vaishnavi Patel

Vaishnavi Patel is a law student focusing on constitutional law and civil rights. She likes to write at the intersection of Indian myth, feminism, and anti-colonialism. Her short stories can be found in The Dark and 87 Bedford’s Historical Fantasy Anthology along with a forthcoming story in Helios Quarterly. Kaikeyi is her first novel. Vaishnavi grew up in and around Chicago, and in her spare time, enjoys activities that are almost stereotypically Midwestern: knitting, ice skating, drinking hot chocolate, and making hotdish.