Translating Holocaust Literature in Times of Genocide

Sasha Senderovich and Harriet Murav on “new ways of seeing the Nazi genocide at a moment when such seeing is urgently needed.”

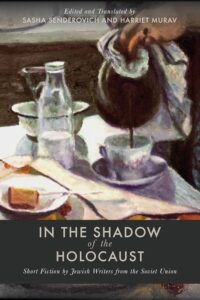

While designing a poster for a lecture on our new book, In the Shadow of the Holocaust: Short Fiction by Jewish Writers from the Soviet Union (Stanford University Press), one of the event’s organizers wrote to ask whether they could remove the word “genocide” from the description we had proposed. The term, we were told, now carried “other connotations.” The stories in our book, translated by us from Yiddish and Russian, are set during and after the Nazi genocide of Jews during World War II. The organizers’ concern was not historical accuracy but political resonance.

The Holocaust may be the paradigmatic genocide. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in the 1940s, when Jews were being exterminated in Europe, but he had become interested in the subject of mass extermination even earlier, when he learned about the slaughter of Armenians in the 1910s. However, naming the Holocaust as a genocide in 2026, the organizers of the lecture about our book feared, would evoke contemporary associations—above all, with the genocide in Gaza.

As many as one-third of all Jewish victims of the Nazi genocide perished on Soviet territory. Yet, for a host of reasons—including postwar Soviet memory politics, the geopolitics of the Cold War, and the marginalization of Yiddish and Soviet Jewish literature—narratives of this experience remain largely unavailable to Western readers. As we write in the introduction to our book, the stories we translated are unique because, given the particulars of Soviet history, many of them involve characters who returned to, and continued to live in, the places where mass violence had unfolded before. This is markedly different from much of Holocaust literature, which is dominated by stories of survivors from elsewhere in Europe who migrated to the United States, Argentina, Canada, Israel, and other countries and who regard their places of origin and sites of their wartime experience from afar.

At the same time, we note that, given the literary power of these stories, they “explore fundamental questions about the Holocaust and other mass killings and genocides of the past and present in Eastern Europe and elsewhere: how to provide testimony, how to memorialize victims, and how to live in the face of overwhelming destruction.”

To insist on the Holocaust’s uniqueness as a shield against comparison risks turning it into an exception that cannot illuminate anything beyond itself

What startled us about the event poster communication was not the suggestion of soft censorship, but how directly it touched upon questions that have accompanied our work on this book since we first began the project about five years ago. First came Russia’s full-scale 2022 invasion of Ukraine, where many of the stories in our book are set, and then Israel’s genocidal assault on Palestinians in Gaza following Hamas’s October 7, 2023, attack on southern Israel. These events forced us to confront what it means to translate and publish literature about Jewish suffering during and after World War II in a present marked by ongoing mass violence.

To translate Holocaust literature at a moment when genocide is not only a historical category but an active legal accusation exposes translators, editors, and institutions alike to pressures to contain, displace, or euphemize violence. This pressure transpires when the violence in question is wielded, in Russia’s case, by a state that rationalizes its genocidal aggression against another people through the moral language of “denazification” rooted in its narratives of victory over Nazi Germany eight decades ago. It also occurs in Israel’s case when the state describes attacks on its citizens—though they possess one of the best-equipped militaries in the world—as akin to violence against defenseless Jews during the Holocaust while citing the Holocaust as part of the state’s moral foundation.

Holocaust memory has long relied on a vocabulary—first and foremost the word “genocide” itself—developed to name unprecedented destruction. That same language is now treated as politically dangerous rather than morally clarifying. As translators committed to making narratives of mass violence available to broader audiences, we find ourselves confronting not only the violence on the page but also the rhetorical maneuvers used to justify the destruction of whole societies in the present or to deny that such destruction is taking place.

These are not stories of salvation. Catastrophe does not ennoble survivors or descendants of genocidal violence, and it does not or make them wiser.

One source of anxiety surrounding the word “genocide” is that it opens the possibility of comparison: between the Nazi destruction of the Jews and the destruction of other peoples. Comparison, we are warned, “relativizes.” But this does not follow. The stories we translated do not compare atrocities; rather, they offer new ways of seeing the Nazi genocide at a moment when such seeing is urgently needed. To insist on the Holocaust’s uniqueness as a shield against comparison risks turning it into an exception that cannot illuminate anything beyond itself, and that cannot, therefore, speak meaningfully to the present.

Even the terminology of “the Holocaust” is far from neutral. The term reflects a particular cultural formation, dominant in the United States and Israel, but not in Eastern Europe or the former Soviet Union. One of our tasks as translators has been to disentangle the meanings this term has accrued from the ways Soviet-era Jewish authors understood, described, and mourned the destruction they lived through. Our translations ask readers to suspend the assumption that the United States, Israel, or the Soviet Union offered salvation to Jews in the postwar world. These stories emerge instead from a landscape of abandonment, silencing, and unresolved loss. Genocide is the deliberate destruction of a people, in whole or in part, along with their culture. The writers we translate understood this reality even without the term.

In David Bergelson’s story “Yahrzeit Candle” (not included in our book), the protagonist describes himself as a man who has lost his entire people. The writers in our volume ask what such loss means. They also ask what it might mean not only for Jews but also for others, as in Bergelson’s story “A Witness” (included in the book), in which a non-Jewish character begins to understand the extent of his own family’s wartime losses only after reading the testimony of a Jewish survivor of a death camp. Universality here is not dilution; it is an ethical demand.

In the Yiddish-speaking world from which most of the writers we translated emerged, the word for the destruction of the Jews was “khurbn”—a Hebrew-derived term originally referring to the destruction of the Temple in ancient Jerusalem and later used for atrocities of World War I and the Russian Civil War. Unlike “the Holocaust”—derived from “burnt offering” in Greek—which is meant to be understood as referring to an event that stands uniquely outside of history, “khurbn” inherently invites comparisons. Were we to publish our book in Yiddish, we would use this word in our title. This backward-looking, memorializing concept of destruction predates the paradigm implied by the term “Holocaust,” and Soviet Yiddish writers drew on it deliberately.

Several stories in our book are themselves deeply concerned with compromised language. Margarita Khemlin, a Russian-language writer born and raised in the Ukrainian city of Chernihiv after the war, began writing only after the fall of the Soviet Union, with full awareness of the distortions littering Soviet speech. In “About Yosif,” her narrator relies on the same clichés as her characters do when recounting the postwar Stalin-era’s period of antisemitic “anti-cosmopolitan” campaigns, in which “cosmopolitan” functioned as a euphemism for “Jew.” She then extends the term backward to refer to Jewish victims of the Nazi genocide in a small Ukrainian town: “What cosmopolitans could there possibly have been in Kozelets in 1950? The cemetery and the ravine near the river were filled with cosmopolitans.”

By seizing on this evasive term, Khemlin inserts Stalinist antisemitism into a longer chronology of anti-Jewish violence that begins with the Nazis. At the same time, because the Soviet state refused to distinguish Jewish victims killed as Jews from the totality of civilian losses during the war, the euphemism ends up naming what it was designed to erase. The story demonstrates how state-controlled language seeks to deny history, and how that very denial can point back to what has been suppressed.

Both Western and Soviet narratives of World War II are anchored in catastrophe and redemption. Neither anchor is ideologically innocent. The stories we translate reject redemption entirely. In Bergelson’s story, the eponymous witness barely survives, and the urgency in his voice comes from the need to document the destruction before he collapses from the exhaustion of living on. In “The Picture in the Teacup” by Dina Kalinovskaya, the family is fractured beyond repair, with the single teacup that remained from a once-full set of dishes absorbing the long history of disruptions and losses. The protagonists may have managed to flee Odesa before the city’s remaining Jews were herded into ghettos, but the violence they did escape is etched onto the topography of the city, to which they returned after the war.

The mother and daughter in Rivka Rubin’s “The Wall” are locked in a nearly lethal conflict that originated at the moment of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union and that, over a decade after the war’s end in the story’s narrative present, continues to fester like an unhealed wound. In “Babyn Yar” and “No Matter When,” Itsik Kipnis writes about people returning to live amidst the ruins of postwar Kyiv—the city’s topography now encompassing an enormous mass grave on its outskirts. Margarita Khemlin lets go of her characters on a concluding note that, to them, appears forward-looking and hopeful but which, to readers familiar with the history that the story’s protagonists are yet to experience, is haunted by tragedies to come.

These are not stories of salvation. Catastrophe does not ennoble survivors or descendants of genocidal violence, and it does not or make them wiser. The protagonists in the ten stories by seven different authors collected in In the Shadow of the Holocaust live next to killing sites for years after the violence had ceased; they carry on in the genocide’s shadow.

That rejection of redemption is precisely what makes these stories indispensable now. American culture has long favored narratives of trauma that end in reconciliation or moral progress. The stories collected in In the Shadow of the Holocaust insist that destruction leaves residues that often cannot be transformed into lessons or triumphs. Translating them today, while multiple genocides unfold in real time, means resisting the urge to soften language, avoid comparison, or shelter the past from the present. It means insisting that the words forged to name one catastrophe and to dwell on its horrific aftermath still matter, precisely because they continue to name others.

__________________________________

In the Shadow of the Holocaust: Short Fiction by Jewish Writers from the Soviet Union edited by Sasha Senderovich and Harriet Murav is available from Stanford University Press.

Sasha Senderovich and Harriet Murav

Sasha Senderovich and Harriet Murav are co-editors and co-translators of In the Shadow of the Holocaust: Short Fiction by Jewish Writers from the Soviet Union (2026). They have previously co-translated David Bergelson’s Judgment: A Novel (2017). Senderovich is the author of How the Soviet Jew Was Made (2022) and Murav is the author, most recently, of As the Dust of the Earth: The Literature of Abandonment in Revolutionary Russia and Ukraine (2024).