Tracy K. Smith on Translating

the World of Yi Lei

"She was and remains a revolutionary voice"

Yi Lei (伊蕾) astounded readers in China when, in 1987, she published a long poem entitled “A Single Woman’s Bedroom.” In it, a female speaker expresses her passion and sexual desire. Again and again, she returns to the refrain “You didn’t come to live with me” as she laments her lover’s failure to make good on his promise, this at a time when cohabitation before marriage was still illegal in China. The poem goes further still, laying claim to a freedom of the mind and spirit, and openly criticizing the rigidity of law:

I imagine a life in which I

possess All that I lack. I fix

what has failed. What never

was, I build and seize.

It’s impossible to think of

everything, Yet more and more I

do. Thinking

What I am afraid to say keeps

fear And fear’s twin, rage, at

bay. Law Squints out from its

burrow, jams Its quiver with

arrows. It shoots

Like it thinks: never straight. My

thoughts Escape.

In other poems, Yi Lei writes as movingly of grief as of love, of joy as of deep unrest. She celebrates and aligns herself with nature, as in this line from “Green Trees Greet the Rainstorm”: “I belong to the nation of wild arms flailing in the wind.” In “Besieged” her vision moves nimbly from the earthbound and everyday to the cosmic, the enduring:

What binds the boundless?

Our tiny minds will come to

grief Trying to imagine what

lies past it. Unfathomable. To

ponder it

Will cost me no small wedge of

eternity, But for that time I’ll be

boundless.

Still not yet widely translated into English, Yi Lei’s work came to me almost by happenstance. In December 2013, I received word from Yuanyang Wang, a Chinese poet and translator, that a poet friend of his would be visiting New York City and would like to meet. A month later, I had lunch in Chinatown with Yi Lei and her friend Nancy Bumin, who, being the only one of us conversant in both Mandarin and English, served as our liaison. It was a cold January afternoon, coincidentally the first day of the Chinese New Year.

I’d been given a rough translation of “A Single Woman’s Bedroom,” and I’d been drawn into the expansive sweep of it. The poem is made up of fourteen related sections that follow almost improvisationally from one another, each driven by a sharp emotional insistence. I felt admiration for this poet’s passion, her sense of play, the ways each new gesture brought in a new gust of energy and indelible imagery. Her poem’s relentless availability to love, even in the wake of betrayal or devastation, spoke to feelings of desire, resistance, and loss that live in and have instigated a number of my own poems.

“Would it be okay,” I’d asked Nancy to ask Yi Lei, “if in certain of my translations, instead of being faithful to the literal features of the poem, I sought to build a similar spirit or feeling for readers of American English?”

There was some back and forth in Mandarin. “Yes,” was the eventual answer.

“I want to make the reader feel at home in these poems. Would it be okay if certain details were to shift or be replaced with others rooted in this culture?”

Again, there was more back and forth across the table. And then Nancy told me that Yi Lei was comfortable with my making these kinds of nuanced choices.

We weren’t even midway through our long New Year’s lunch, yet I was brimming with joy at the prospect of living awhile in the vision and vocabulary of these poems and this imagination. Yi Lei trusted me to live with and respond to her poems, and to offer them to readers in the way that I heard and felt them. It was a remarkable freedom and a daunting responsibility. And, yes, I was already committed to the task of shepherding this indispensable voice into a living contemporary English.

My strategy, whenever I reached a point of hesitation, was to ask the surrounding features of the poem to suggest a continuity that might guide me forward.

Four years later, I took my first trip to visit Yi Lei in China. My flight landed in Beijing hours late, and I moved slowly, with a battery of tired travelers, through customs and immigration. It was nearly two o’clock in the morning, but Yi Lei and my cotranslator, Changtai Bi (who goes by the name David), were waiting to welcome me. Of Yi Lei’s hospitality during that visit, all I can say is that I thought my heart would burst from gratitude at the beautiful entrée into her world that she’d provided, for it was with a quiet exuberance that she afforded me a glimpse into China’s complex past and its many-layered present. Most emphatically, spending a week in Beijing allowed me to get to know Yi Lei in her own element, with her peers and protégés, friends and family; to see her negotiating her city and decoding her own history for an eager guest. I recognized in her person the largeness of spirit, the agelessness, the fearless availability to experience, and the inner nobility that animate her poems.

Happiest are the brief flashes of memory: holding her hand as we hurried along a bustling block; her pointing my attention to people, foods, and architecture signaling a way of life now all but gone. We spent my last afternoon in Beijing with her niece, Yisha, pulling canvases down from the many racks of the studio where Yi Lei lived and, in recent years, made paintings. In the last three decades of her life, Yi Lei painted hundreds of beautiful and arresting figurative canvases: probing self-portraits; series upon series of roses, peonies, and lilies which speak to states of joy, loss, and transcendence. I came away with yet another understanding of the vast self to which she gave voice in her poems.

Once, over dinner and with David translating, Yi Lei told me the story of the great love that inspired “A Single Woman’s Bedroom.” In our 21st-century shorthand, I will say, simply: it was complicated. I envied Yi Lei’s ability to claim the fact of that love, and to embrace the joy and upheaval it led to without apologizing for it or turning against it as is sometimes the case when one looks back at the many detours of one’s own youth. “Love is innocent,” she said. And with that simple phrase, I believe she explained parts of myself to me, which is, of course, what great poets do.

The last time we met, six months later, Yi Lei offered me feedback on my translation of “A Single Woman’s Bedroom.” In particular, she wanted me to attend better to the poem’s later sections, which I had initially translated with too much emphasis upon romantic love. She wanted me to see that her poem turns from a fixation upon the liberation of sensual love to an urgent insistence upon the individual’s freedom from unjust institutions. The pined-for beloved, as the poem progresses, is no longer a man, but an essential concept. And the disappointment driving the poem is leveraged finally, and importantly, against the self. “A Single Woman’s Bedroom” concludes with these lines:

14. Hope Beyond Hope

This city of riches has fallen empty.

Small rooms like mine are easy to

breach. Watchmen pace, peer in,

gazes hungry.

I come and go, always alone, heavy with

worry. My flesh forsakes itself. Strangers’

eyes

Drill into me till I bleed. I beg God:

Make me a ghost.

Fellow citizens:

Something invisible blocks every

road.

I wait night after night with a hope beyond

hope. If you come, will nation rise against

nation?

If you come, will the Yellow River drown its

banks? If you come, will the sky blacken and

rage?

Will your coming decimate the harvest?

There is nothing I can do in the face of all I

hate. What I hate most is the person I’ve

become.

You didn’t come to live with me.

Yi Lei died suddenly in the summer of 2018 while traveling in Europe. She was and remains a revolutionary voice in Chinese poetry. I feel immensely fortunate to be able to say, from firsthand knowledge, that she was huge-hearted and philosophical, on intimate terms with the world in the way of Walt Whitman, one of her literary heroes.

This volume was nearing completion when David startled me with the terrible news of Yi Lei’s death. We had spent part of the previous autumn in Beijing discussing the progress I’d made with her poems. Our manner of collaborating was this: working from David’s literal translation of a manuscript of Yi Lei’s poems, I would listen to the poem’s statements and the images, essentially trying to visualize the poem’s realm, and to align myself with the feeling and logic of the work. Then, I’d attempt to re-envision and re-situate these things in English. Occasionally, this was a matter of shifting toward smoother, more active, evocative language. Often, it entailed locating a relationship between verbs and nouns and aligning those features within a new metaphor or image system, as occurred in this passage from David’s literal translation of “Love’s Dance”:

When you quietly evaded

It seemed that land sank in front of the

chest My shout was blocked by echoes

It was invisible hands that forged my

mistake To avoid a pitiful tragedy

I strangled the freedom of souls

To let my reason be pitch-black from

then I am willing to be dominated by

you

I allowed land sank, blocked, echoes, forged, tragedy, and pitch-black to guide me toward the metaphor of mining, which resulted in this passage from my version of the poem:

What happened deep in the mountain of

me. And then the mine in collapse. The

shaft

Choked with smoke. Voice burying

voice. An absence of air,

preponderance of pitch.

I don’t want to know, or understand, or be

restored To reason. In the wake of certain

treasons, I am

Still domitable, a claim in wait. I am

Possessed of my depths. I am willing

still.

My strategy, whenever I reached a point of hesitation, was to ask the surrounding features of the poem to suggest a continuity that might guide me forward. Sometimes, I’d make a leap of faith, trusting to the larger energetic pull of the poem to keep me from losing the trail. Then I’d send my work to David, who would translate it back into Chinese for Yi Lei. Yi Lei read my version for feeling, image, and intention. If she recognized in my poem something essential from her original, we let things stand. Our conversation took place back and forth in this triangulated fashion.

I have sought, in my translations of Yi Lei’s poems, to cleave to the original spirit, tone, and impetus. But it is important to recognize that often they do so by veering away from the vocabulary, or occasionally the form, of the original. In addition to the literal deviations described above, I also accepted the fact that the music of the original, which I wasn’t capable of recognizing in the Chinese, or gleaning from David’s intermediary translation, could not be a component of my concerns as a translator. What I hope emerges clearly for readers in English is some of the rhythmic and emotional insistence of Yi Lei’s use of statement, repetition, and refrain.

I trust that this bilingual selection of Yi Lei’s poems will allow readers of both languages to grasp and assess the choices I’ve made in the translations, while also presenting the original work in its own terms. Across the English and the Chinese, readers will hear, perhaps more than anything, the conversation that took shape between Yi Lei’s poetics and my own. Perhaps that conversation will, in turn, embolden someone to translate these poems based on other principles, giving them new forms of existence and further enlivening the conversation about the work of this brilliant and essential poet.

I offer tremendous and ongoing thanks to my cotranslator David Changtai Bi for his good humor, generosity, and tireless work in ferrying versions of these poems back and forth across languages. David’s long friendship with Yi Lei has been a source of insight and consolation indispensable to the completion of this volume.

__________________________________

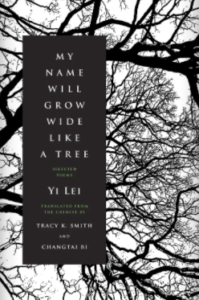

Introduction from My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree. Copyright © 2020 by Tracy K. Smith. Used with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis,

Tracy K. Smith

Tracy K. Smith is a librettist, translator and the author of five acclaimed poetry collections, including Life on Mars, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. Her memoir, Ordinary Light, was a finalist for the National Book Award. From 2017 to 2019, she served as the 22nd Poet Laureate of the United States. She lives in Massachusetts.