Toward a Theory of the New Weird

Elvia Wilk on a Feminist Understanding of Eerie Fiction

But the literal becoming-plant that happens in these stories suggests the potential for agency in the willing dissolution of self. Knowing how to dissolve and become other is a non-codified and embodied kind of knowledge that women, and other supposedly unstable bodies, have been cultivating for centuries, because they’ve had to. Given the reality of planetary extinction, driven by the notion of the human as bounded figure with unique agency over the landscape, one could argue that this is exactly the type of knowledge currently needed. This is a knowledge about how to actively annihilate the supremacy of the self, and in turn the category of human selves altogether. This is the knowledge that death by landscape is not death at all; where landscape is not a threat, but a possibility, perhaps the only possibility. Donna Haraway puts it best when she says this is a kind of situated knowledge that“requires that the object of knowledge be pictured as an actor and agent, not as a screen or a ground or a resource.” Haraway is talking about women here, but she’s also talking about plants.

I didn’t know about the category of New Weird while writing my recently published novel Oval. I was surprised and also a little uncomfortable to find I had been inhabiting the weird all along. The book’s setting is an alternate version of the city of Berlin, which is most obviously differentiated from the real version by the imposition of a fictional mountain in the city. The main character is a young scientist named Anja, who lives in relative isolation in an eco-community on the mountain, with her boyfriend, Louis. As the story develops, Anja becomes increasingly physically affected by the artificial ecosystem in which they live. The divisions between natural and artificial, scientific knowledge and embodied knowledge, and person and plant (figure and ground) dissolve as she habituates and becomes.

As a scientist, she obsesses herself with trying to taxonomize and explain the world around her, but on the mountain she begins to interpret her bodily and emotional reactions as forms of valuable information themselves. What does a strange rash indicate about the state of the environment, the state of her relationships? Much of what happens in the plot can be explained through cause-and-effect, but there is, I hope, an eerie excess that remains.

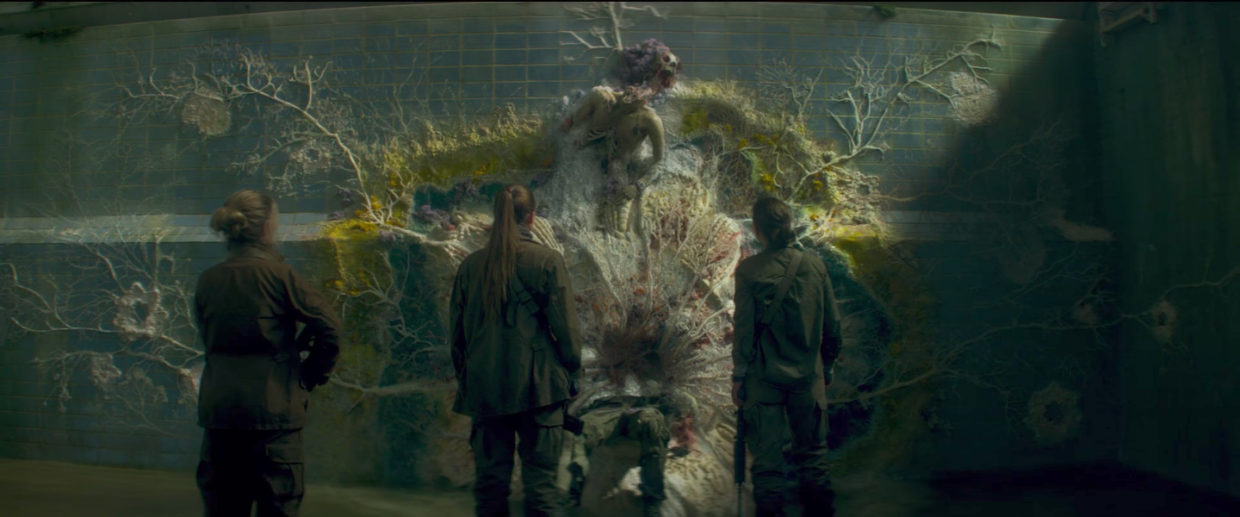

Still from the movie Annihilation (2018)

Still from the movie Annihilation (2018)

Weirdness is a confrontation with the nonhuman. Weird knowledge does not deny the capacity of the human mind and body to produce knowledge, but it does not reduce the world to human subject experience either. Unlike science fiction—in which there is a rational explanation for everything—and fantasy—where magic explains it all—weirdness hovers between poles of explainability.

This makes New Weird something of an anti-genre, a genre whose uniting factor is paradoxically in remaining outside categorization. Yet it’s been given a semblance of cohesion, according to a shared set of aesthetic sensibilities, by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, in the 2008 anthology The New Weird (and another simply called The Weird in 2012). VanderMeer is also author of the very weird Southern Reach trilogy, the first book of which, Annihilation (2014), involves a woman-becoming-nonhuman. In the book, a team of women enter a mysterious zone known as Area X, where an eerie nonhuman agent seems to be taking over or “infecting” the landscape. The narrator, a biologist, at first tries to examine the plantlife of Area X to explain what is happening around them, but eventually her own sense perception becomes warped by the environment she is herself becoming part of—she inhales the spores of an organism she is studying, which affect her perception. She’s forced to admit that she can no longer claim status as a detached observer; she has become an unreliable narrator by dint of becoming part of the ecosystem she is observing.

If living in a new weird ontology is the only way for people to keep living, what do we want to keep of ourselves?

The biologist and her colleagues react in different ways to the creeping understanding that they are becoming plant—or alien. These are versions of the classic ways the literary scholar Jim Clarke says that humans tend to encounter the weird Other: to fight, to flee, and to attempt to understand. In the case of Area X, none of these works. The new nature does not respond to human violence. Its encroach is inescapable; it takes you over from the inside out. And it cannot be explained according to rationalist epistemology. It can only be experienced and felt. This experience constitutes its own form of knowledge, an embodied knowledge rooted in place.

Annihilation presents core ambivalence about this planetary takeover. For her part, the biologist struggles to decide whether becoming is succumbing, or the opposite. Or maybe both. Is it “death by landscape” or is it “life by landscape”? If living in a new weird ontology is the only way for people to keep living, what do we want to keep of ourselves? What does coexistence look like when coexistence requires deconstructing the self on a cellular level? Is it possible to consent to, and then claim agency over one’s own dissolution?

Near the end of her account, the biologist says of the transformation of nature and herself: “I can no longer say with conviction that this is a bad thing. Not when looking at the pristine nature of Area X and then the world beyond, which we have altered so much.” She can no longer see her decreation, nor the decreation of the current human-centric world, as negative or terrifying. Loss of bounded self is only truly horrifying within an anthropocentric framework that prizes human being in its current state over all other forms and ways of being.

The fantasy of woman-becoming-plant is an ambivalent fantasy. On one level, it’s no less romantic than any back-to-the land fantasy. That kind of fantasy sees nature as distinct and permanent and unchanging and passive and authentic and fundamentally good. Back-to-the-land is the fantasy of a quick fix: we’ll just become natural “again” and begin a process of reversal of the Anthropocene. But taken in its full weirdness, which is weird precisely because it is so literal—a plant springing from a woman’s arm—becoming plant need not be about reversal or reversion to some imagined natural state. On the contrary, it’s about seeing ourselves as always already plant, plant as always already human, and those distinctions as always already weird.

Still from the movie Annihilation (2018)

Still from the movie Annihilation (2018)

Human is a useful category, in that it has historically been able to confer equality among humans (or at least tried to do so), and in that it allows us to take responsibility for what we’ve done to the planet. But zoom in through the microscope: you’re made up of trillions of other creatures. And zoom out: you’re one part of vast ecosystems. The category doesn’t hold. And without that category, the central importance of the human to the story of the planet is no longer self-evident. Further, given the current knowledge of the extreme permeability and ecological codependency of all bodies, there’s no reason any body should be excluded from having to learn how to become plant.

Fictions are important because they provide points of access through the human technology of the story to gigantic ecosystems made of humans and nonhumans alike. This reconciliation of vastly different scales, of figure and ground, is necessary at a time when we are so aware of the magnitude of humanity’s negative affects and yet as individuals we struggle to make tangible ecosystemic contact. As theorist Wendy Chun has put it: you can’t experience the climate; you can only experience the weather. So how can a person feel a planetary-scale system? What do (eco)systems do to the body?

Fiction foregrounds human subject experience without reducing the universe to human subject experience—it preserves the room for the irreducible difference of the ginkgo or the orchid or the moss. In that way it potentially moves beyond the two options we’re usually given for the way the future can go: utopia or dystopia. It allows us to ask: whose utopia, whose dystopia? If the human is not the protagonist, which one is which? A utopia for mosquitoes may not be the same as mine, but from the perspective of planetary ecosystems it may be far preferable.

In other words, utopia and dystopia are happening all the time, right now, on different scales and in different places. In trying to construct a future imaginary that neither glorifies dystopia nor reaches blindly toward utopia, in a way that neither explains everything or gives up on explanation, we can’t go on fighting or fleeing or attempting to understand according to current frameworks.

When a person enters a coma, the person is said to enter a vegetative state. The derogatory word is vegetable. Becoming plant, one would think, is to become less than human, to relinquish agency, to immobilize oneself, to stop moving forward. But moving forward hasn’t worked. In fact, rooting oneself and becoming plant can be a vicious claim to life. It is not the same as life now, but it is life. Such a “death by landscape” is a kind of life through landscape, life only possible through landscape. At the end of the Atwood story, the woman who lost her friend hears a human-sounding shout from one of the landscape paintings. It’s not a shout of fear, like she might have thought. It is a shout, she says, of “recognition or of joy.”

Thanks to the Young Girl Reading Group for finding and reading these stories with me.

_______________________________________

Elvia Wilk’s novel Oval is out now from Soft Skull Press.

Elvia Wilk

Elvia Wilk is a writer and editor living in New York and Berlin. She writes about art, architecture, and technology for several publications, including frieze, Artforum, e-flux, Metropolis, Mousse, Flash Art, Art in America, and Zeit Online.