Meeting engraver and artist Tuulikki Pietilä proved a turning point in Tove Jansson’s life. They found one another at the Artists’ Guild Christmas party in Helsinki in 1955, at the gramophone where the two of them were looking after the music, and their relationship gradually developed in the course of the following spring. “At last I’ve found my way to the one I want to be with,” Tove Jansson wrote in one of her first letters to Tuulikki Pietilä in the summer of 1956.

They had spent a few days on Bredskär and their love was deepening. I feel like a garden that’s finally been watered, so my flowers can bloom, Tove Jansson confided to her beloved, who had gone to teach at an “artists’ colony” in Korpilahti for a few weeks. Tove Jansson was left alone on the island, but she felt calm and full of confidence.

The letters to Tuulikki Pietilä contain a succession of love metaphors about blossoming and abundance, imagery that also recurs later on, in a poem to “Tooti” in 1985. Here she is likened to an orange tree.

I would compare you to this sturdy tree

lovely to live with in all its finery

and all the fruits that its branches do adorn

are your desires for projects yet unborn!

In the summer of 1956, Tove Jansson drew a picture of “a new little creature” in one of her letters and Tuulikki was transformed in the name of love to “My Too-tikki”. In the sixth Moomin book Trollvinter (1957, Moominland Midwinter), the name took on its Moominesque form of Too-ticki. Large parts of the book were written during the winter she spent with Tuulikki Pietilä at the latter’s studio on Nordenskiöldsgatan in Helsinki. Privately and within their close circle of friends, Tuulikki Pietilä was known as Tooti. She and Tove Jansson lived together for 45 years.

They had already encountered one another a few times in their earlier lives. Both were studying at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts (Ateneum) in 1938, and in 1951 their paths crossed at the famous Monocle nightclub in Paris. Tuulikki Pietilä had been living in the city for a few years and Tove Jansson was on her way home from travels in Italy and North Africa. Paris assumed a special significance for the couple; it was the city they loved above all others.

Tuulikki Pietilä (1917–2009) was born in Seattle but moved back to Finland (Åbo) at the age of four. She was the daughter of Frans and Ida Pietilä (née Lehtinen). Her brother Reima Pietilä (1923–93) became one of Finland’s best-known architects. Tuulikki Pietilä herself attended the Åbo Academy of Fine Arts (1933–36) and then went to Helsinki to study at the Ateneum (1936–40). In the war years she was in East Karelia and later worked in Sweden, looking after child evacuees from Finland (1944).

After the war she lived in Stockholm while she trained in etching at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (1945–49). On moving to Paris she took tuition at various establishments including Académie Fernand Léger and studied with the eminent engraver Louis Calevaert-Brun. She also taught for a time. She did not return to Helsinki until 1954, after almost a decade abroad. She went on to teach engraving at the Academy of Arts (1945–60), and wrote a textbook on metal engraving. Her exhibitions can be numbered in the hundreds. Tuulikki Pietilä was awarded a professorship in 1982.

In Tuulikki Pietilä, Tove Jansson found a traveller, seeker and freedom-lover just like herself. This was something new. In her youth she had travelled alone, later with Ham (and with Faffan a few times), and occasionally with friends. But now she had a travelling companion on equal terms. “Tooti is fantastic, of course, she always is—but a Travelling Tooti is something exceptional”, Tove Jansson wrote to Maya Vanni from Vienna (April 23rd, 1982).

The short-story collection she published five years later, Resa med lätt baggage (Travelling Light) was dedicated “To Tooti” (1987). Interviewed at some length by Helen Svensson for the book Resa med Tove (2002, Travels with Tove), Tuulikki Pietilä talked about life on their many trips. They journeyed as the fancy took them, never booking hotels in advance. On their first trip together, in 1959, they visited Greece and Paris. they also travelled separately, and Tove Jansson would write to Tuulikki Pietilä. Sometimes she would be on the island while Tuulikki Pietilä was in the city and sometimes the other way round. In later years there was no need for them to write to one another. As they grew older, they increasingly both lived in Tuulikki Pietilä’s studio flat at Kaserngatan 26C.

The letters to Tuulikki Pietilä are all about love and work, recent and present, but a shared future is in their sights from the outset: “I love you as if bewitched, yet at the same time with profound calm, and I’m not afraid of anything life has in store for us” (June 26th, 1956). As the years passed, the narrative of their lives seen unfolding in the letters changed and evolved, but its basic premise remained the same. On the island they lived together (often in a tent), but in town they lived their own separate lives, albeit under the same roof.

In the early 1960s, Tuulikki Pietilä moved to a flat in the same building as Tove Jansson’s studio—the building was on a corner—and they simply walked across the attic to see one another. The letters reveal their life on Bredskär, increasingly preoccupied with family and friends as time passes, and subsequently on Klovharun—their island—once Bredskär grows overcrowded and starts to feel claustrophobic. They quite literally built their life, piecing it together with work and love, but the process was not painless.

Anyone who lived with Tove Jansson also had to live with her family. After Viktor Jansson’s death, Signe Hammarsten moved to Lars Jansson’s, but she spent the weekends with Tove Jansson. Relations were distinctly strained at times and, in a letter to Vivica Bandler in the summer of 1964, Tove Jansson wrote of the need for a break. Tuulikki Pietilä would install her new lithography equipment at Kaserngatan and then go to Venice to supervise an exhibition; “she needs her own surroundings and the stimulation that a new working technique can provide”, wrote Tove Jansson, citing “the old Ham friction” that was bound to set in again before long.

It is another Tove Jansson we encounter in the letters to Tuulikki Pietilä, open and sharp yet also trusting. Tuulikki Pietilä also receives some unusually frank comments from Tove Jansson about her Moomin work—everything from merchandise to texts and illustrations—sometimes including hilarious accounts of her growing fame and everything that goes with it, book tours, public appearances, trips and huge numbers of encounters with people of many different kinds.

“All things are so very uncertain, and that’s exactly what makes me feel reassured”, says Too-ticki in Trollvinter (Moominland Midwinter). Life with Tove Jansson brought changes for Tuulikki Pietilä as an artist, too. The letters clearly show that collaborating on projects played an important role in their lives. They worked on the world of the Moomins, constructing Moominhouses and tableaux with their friend Pentti Eistola; they mounted a joint exhibition (Jyväskylä, 1969); and they published a book in words and pictures about their life on Klovharun, Anteckningar från en ö (Notes from an Island) in 1996.

Quite a number of Tove Jansson’s literary works can be traced back to her life with Tuulikki Pietilä, from Trollvinter (Moominland Midwinter) to the novella Rent spel (1989, Fair Play), a portrayal of two women’s life together. One is an artist, the other an artist and writer. In the final chapter, “The Letter”, the artist has been awarded a scholarship to go to Paris, yet is hesitant about leaving her partner and making the trip alone. But, for someone who is “blessed with love”, as the final words of the story have it, solitude presents its own opportunities.

*

June 26th, 1956 [Bredskär]

Beloved,

I miss you so dreadfully. Not in a desperate or melancholy way, because I know we shall soon be with each other again, but I feel at such a loss and just can’t get it into my head that you’re not around any more. This morning, half awake, I put a hand out to feel for you, then remembered you weren’t there, so I got up very quickly to escape the emptiness. And worked all day.

The science fiction synopsis is done now, it took about 15 more strips.

This morning I roused the social conscience of the whole of Viken and wrote an application to the county sheriff on behalf of seven penitents without fishing licences. Then I was at Odden and admired all Anna-Lisa’s planting and concreting and other curious arrangements, and was given a whole basket of little plants that I’ve popped into the ground, dotted around the Island.

The Island looked very solemn without you when I arrived here at sunset. It had turned in on itself and I felt like a virtual stranger.

It was only when I got up to the house that it looked friendly and alive again. The wagtails were yelling in great agitation, complaining volubly because the copper jug we had our midsummer leaves in had fallen down and clearly frightened their babies out of their wits. They probably got a dousing as well. Now the idyll has been restored and the mother is so tame she stays perched on the top of the flagpole even as I go in and out of the house. I brought some mud for the swallows from Anna-Lisa’s bay—but they continue with their furtive visits and seem reluctant to commit to family life.

Late one night I started off some kilju in the “best water bucket” and supplemented the recipe with all our raisins.

It was a fine night, calm and quiet, and I still couldn’t take it in that you weren’t here, kept half turning round to see what you were doing or to say something to you.

“You see, I love you as if bewitched, yet at the same time with profound calm, and I’m not afraid of anything life has in store for us.”Today there’s a strong south-westerly blowing and we would have found it hard to get over to Viken.

So I assume you’ve now plunged deep into the all-engulfing life of the city and are dashing about getting hot and resentful so everything’s ready for your departure.

That first day in town is always such a horrible contrast to life out here on the island. Everything that’s been lying in wait for you comes tumbling in like one big shock and at nights you miss the sound of the sea and feel totally lost.

Wherever I go on the island, you’re with me as my security and stimulation, your happiness and vitality are still here, everywhere. And if I left here, you would go with me. You see, I love you as if bewitched, yet at the same time with profound calm, and I’m not afraid of anything life has in store for us. This evening I filled the tub with water from the big rock hollow and tried to pick out the dreadful Sea Eagle Waltz on the accordion. I’ll play it for you! Now I’m going to read Karin Boye and then go to sleep—good night beloved.

*

27th.

Today I brushed and cleaned the hollow after I’d emptied it and then sprinkled sand into it like you told me to.

And I wrote that awful article for Svenska Dagbladet, “What it’s like to write for children”, which I’ve felt uncomfortable about for so long. I tried to spice it up with the kids’ own healthy taste for the macabre, the obvious and the reckless, in the healthiest sense, and to write as little as possible about myself and my blessed old troll.

Then I hauled stones to make a fine terrace in that place where the grass is yellow and started thinking about the next synopsis, the one where Pappa is a lighthouse keeper. A story about the sea and different sorts of solitude, and everything that can happen to you along beaches. But I’ve no clear idea of how I want it yet.

The wine is bubbling away madly and the place smells like a moonshine factory. It’s spitting with rain on and off and the sea is grey and austere.

*

28th.

Suddenly there’s lots going on again. I’d hardly had time to make the bed before Björn Landström came over the hill, with Vivica after him—they’d both arrived by water taxi.

The first thing Uca did was to ferret out your letter, and after an enormous amount of coffee drinking and going through the Moomin advertisements for the Co-op Bank and seeing Landström off, I was finally able to read the letter.

You’re right that it always tends to be easier to go than to stay—even if you’re happy being with the one you are leaving. I know. But this time it would have been more right and natural for us to stay with each other.

I can’t help feeling terribly smug that you long to be back here.

I’m waiting for you already.

Everything I do, everything new that I see—there’s a parallel reflection: I shall show this to Tuulikki. Waiting is a sheer pleasure when it’s for you—and the calm awareness that all I have to do is add together a number of days, and we’ll see each other again. I haven’t dared try the mosquito song. That would make me sad and I’d miss your embrace so much.

It’s wonderful that your brother got the Brussels Prize! That’s a really great accolade. And it’s excellent that you simply took a taxi and went straight round to celebrate with him, not worrying about the whole sensitive family situation!

“I’m so unused to being happy that I haven’t really come to terms with what it involves.”I’m sure the two of you forged a new kind of contact that evening, perhaps found you could be natural with each other like before. Uca told me about the prize, too, and everything you both said when you met, and you more or less insisting she came directly here, which made her incredibly glad and proud. She’s sound asleep beside me, exhausted. The Paris séjour went well, but it was all a lot of trouble, and the reaction afterwards, and now she has a long, overwhelming year of theatre ahead. She’s tired but composed, and pleased with the results of her work, and we’ve let the day go by just talking to each other.

Thank you for the fly swatter my darling, it seems extremely effective. To think of you remembering it amidst all the rushing about, “dark love” and picture hanging and exhibition planning and what not!

I appreciate that you haven’t had time to go to a doctor, but it worries me a lot that you couldn’t.

How is your knee? Does it feel any worse? I can understand your insides being in tumult. They don’t like having to move from place to place, and demonstrate it by rearranging the days all wrong. Can’t we wait a few more days for each other in August so you’ve time to go and get the wretched thing looked at? Beloved, I understand your lack of relish at the prospect of Korpilahti. But just think, this is the last time ever! Then we can do whatever we want with our summers.

And our winters, the whole lot! I’m so unused to being happy that I haven’t really come to terms with what it involves. Suddenly my arms are heaped full of new opportunities, new harmony, new expectations. I feel like a garden that’s finally been watered, so my flowers can bloom.

10221!

The last evening with Uca—tomorrow she goes home and Ham and Faffan will probably come out. We still haven’t done anything but talk; it’s so rare for us to be on our own together, and so much has happened since the last time. But the strange thing is that, whatever I talk about, it always seems to come back to you, and I sing your praises in uncontrollable dithyrambs. She doesn’t contradict me.

Goodnight darling. Look after yourself.

Tove.

__________________________________

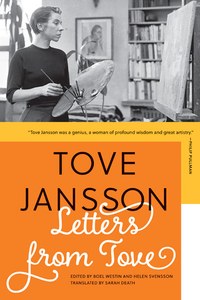

Excerpt from Letters from Tove by Tove Jansson, edited by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson, translated from Swedish by Sarah Death (University of Minnesota Press, 2020). Letters from Tove © Tove Jansson/Moomin Characters™. Selection, introduction, commentaries © Boel Westin and Helen Svensson. English translation © Sarah Death and Sort of Books. Used by permission. All rights reserved.