The museum was hosting a Swedish video artist’s first American exhibition. This Swedish video artist: her work is largely about female pain. By female pain I mean female subjugation and exploitation, and humiliation. By female pain I mean her pain. She makes, in her art, a spectacle of herself.

I drove down the coast to the museum and at the museum, I met my friend. My friend, tall and dark- haired. She kept her sunglasses on when we went inside. She had broken up with her boyfriend and called me and I had driven down. She had been crying all morning. “Fiancé, I guess. I never wore the ring.” Rather: he had broken up with her.

Did I, do I, admire the artist for claiming her pain is worthy of art, or did I, do I, find the act of aestheticizing also trivializing, or in fact is that feeling, that impulse to call the art trivializing, a way to conceal the true feeling, guiltier, that her art is vulgar, that it is indulgent, because she is her own subject? Because she elevates herself as subject? The woman as object is less vulgar than the woman as subject. The woman as object is art and the man who objectifies her an artist. The woman as subject, well. Just a narcissistic bitch, isn’t she? Not that I believe this. Not that I do not believe this.

*

In one room of the museum a series of screens had been mounted. On one screen: a ballerina in pink and her male partner in black, his hands firm about her waist. In the eighteenth century, the ideal wife’s waist was no larger than the span of her husband’s hand. On another: two opera singers, one male, one female, mouths open, chests heaving. Bad luck if your husband had short fingers, diminutive palms. On yet another: a stage, a curtain, red velvet, drawn, and a woman, pacing, declaiming on the proscenium. At her heels, nipping and barking, a terrier, brown and white. Occasionally the terrier reared up on its hind legs and pawed at the tails of the woman’s button-front shirt. There were more screens—a man and a woman running hurdles on a track; what might have been a job interview, with a man, suited, behind a desk, if not for the woman before him, her hair shorn, her body encased in sackcloth—and, next to each, a pair of headphones.

Several years before, the Swedish video artist had divorced her husband. Her second husband, I am moved to say, in the spirit of pettiness. I am, myself, once married. The day I met my friend at the museum, I was not yet divorced. The Swedish video artist and her husband had two children together. During the divorce proceedings, the husband sued for full physical and legal custody of both children. He charged that his soon-to-be ex-wife was an unfit mother. The case went to court. Several videos by the Swedish video artist were entered into evidence. There she was, in a bathtub, naked, bleeding from between her legs: a miscarriage. In her hands, a copy of The Odyssey. She reads from Book Twenty-Two, the slaughter of the suitors. There she was, in chain mail, in the kitchen, preparing dinner. Beneath the chain mail—this is her husband’s lawyer—I will draw your attention to the fact that beneath the chain mail respondent is completely nude. She serves dinner—bowls of soapy water; a salad of unwashed weeds; uncooked spaghetti, halved, covered in motor oil—to a family of blow-up sex dolls. She goes into another room and retrieves a sword. With the sword she decapitates each sex doll. Then she sits down at the table and begins eating the dirt-covered weeds. In court, during the Swedish video artist’s testimony, the judge seemed unable or unwilling to look her in the face. Her husband, I should say, was American, as was his lawyer, as was the judge, and it was of course in America that this trial took place. In Connecticut. The Swedish video artist was granted supervised visitation: three hours, twice a week. She chose, in defiance of the custody agreement, to return to Sweden. To abandon her children. I am quoting contemporary press accounts, though it is always possible that I am quoting them inaccurately. The day I met my friend at the museum I, myself, did not yet have a child.

After the trial was over, the Swedish video artist obtained a transcript of her exchange with her ex- husband’s lawyer. She made copies of the exchange and distributed these to a handful of female artists she respected: a choreographer, a librettist, a play- wright. There were others: a filmmaker, possibly also a poet, possibly also a rhythmic gymnast. She asked them to choose performers they themselves respected. And then she filmed the performances.

At the museum, at the far end of the room in which the screens had been mounted, above one closed door, wall text, the letters large, black, press- on, the font a sans serif: “The Story of the Children.” I tried the knob of the door and found it would not turn. Presumably this was a metaphor.

“It seems,” my friend said, “like cheating. They do all the work, and she gets the show.”

“It was her idea.”

“If she were a man, you’d call this exploitative.”

“But she’s not. Historical context. It matters.”

“The point of feminism,” my friend said, “isn’t to replicate existing power structures, only with women in control. Or it shouldn’t be.”

“How did you get here?”

“I called a car. You know public transportation here is—”

“And presumably you know that saying the words existing power structures doesn’t mean you’re not part of the problem?”

“How was I supposed to get here, then?”

I twirled one finger in imitation of a game-show wheel. “And the winner is . . . biking! One of very few ethical modes of transportation—provided of course that the bike was, when you purchased it, used. You should have biked.” Do my words sound cold, even cruel? Perhaps it helps to know that as I said this, I was smiling.

“And get my clothes all sweaty? No thank you.” “Your choice.”

“How did you get here?”

“My car’s electric.”

“Your car’s a hybrid. Excuse me, your husband’s car is a hybrid.”

“Same difference.” I would not call us, my friend and I, liars. Nor would I call us, in general, honest.

“Patently false.” Instead I would say that one of the premises of our friendship, a friendship that I have, in the years since our visit to the museum, let lapse, was that we were honest if with no one else then at least with each other. And that to force this honesty, we were compelled also to be cold, also to be cruel, to each other.

“Are you saying,” I asked, “that you’d rather I wasn’t here?” Also that this cruelty was, for us, a way to commune. A source, even, of joy.

“No,” my friend said. “Are you saying you’d rather I wasn’t here?”

Isn’t that the test of love? The test of intimacy? The willingness to be cruel and the belief that, the moment of cruelty passed, the love, the intimacy, remains, undamaged?

“No.” Yes, it is.

“Good.”

Or at least I have at times believed this to be the case.

“Good. Now. Do you want to tell me about your breakup.”

My words were phrased as, but in fact were not, a question. My friend rolled her eyes. Rather: she made the head motion—from left to right and then up a tick, her skull sketching the shape of an upper-case L—that I associated with her eye rolls, which were frequent. I could not see her eyes because she was still wearing sunglasses. “Well. What do you think happened.”

“He found out you were cheating on him.”

“Correct.”

Another of the premises of our friendship was that we loathed emotional intimacy even as we understood its necessity. Speaking with casual nonchalance about subjects that caused us great pain was our preferred workaround.

“If you were a man, I’d call you a cad.”

“Sure, if this were the nineteen fifties.”

“I’d be ethically obligated to take the wronged woman’s side.”

“If I were a gay man? Or a lesbian, for that matter. Or a straight man, but trans. Say I were nonbinary, or my partner was.”

“I’m just saying. The point of feminism isn’t to replicate existing power structures only with women in control.”

“You don’t say.”

“The fact that you’re a woman cheating on a man doesn’t make the cheating itself any less morally reprehensible.”

“Precisely what Paul told me this morning.”

“Really?”

“No. He said, Now I know why you never wanted to wear the ring.”

__________________________________

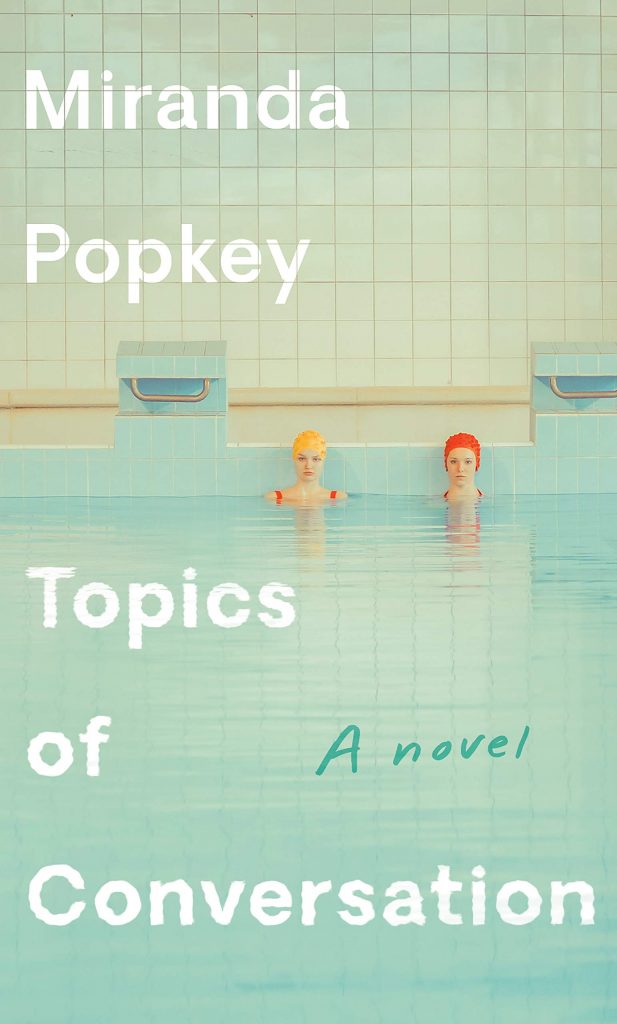

From the book: TOPICS OF CONVERSATION by Miranda Popkey. Copyright © 2020 by Miranda Popkey. To be published on January 7, 2020 by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.