Too Good To Be True: How Angels Continue to Inspire

Ed Simon Considers the Cultural Legacy of These Heavenly Archetypes

Unlike Ezekiel or Enoch, Elijah with Elisha, Mary and Muhammad, I’ve never seen an angel, though I can’t be certain that I’ve not experienced one. There hasn’t been a clear theophany in my life, no visions of rotating disks in the heavens, of celestial beings affixed with eyes imploring me to fear not. I haven’t supped with angelic strangers in the desert like Abraham and Sarah, nor have I heard the trumpet blast of Gabriel or seen the glint of Michael’s sword. I’ve not conjured any such beings as did Medieval alchemists and Renaissance occultists; Moroni has not unveiled himself before me in the woods. But there are certain moments of incandescent, otherworldly, illuminating and unifying beauty which seem to project themselves within as if they came from without, so that the word angelic might at least be somewhat appropriate.

A handful of these occurrences in my life, and I don’t think that such experiences are entirely uncommon, though in our disenchanted world talking about them may afford you a sidelong glance from the sectarians of secularism amongst us. Mundanity must be the operative setting of any authentic angelic experience, for how else do you recognize that which is so miraculously unexpected as being real? Those who go searching for angels inevitably convince themselves that they’ve found them; it’s the uneasy visions among the unprepared that announce themselves. In my case, I happened to be sitting on my faux-leather couch, dusted in crumbs and stains, in my former apartment that overlooked the Lehigh Valley and the crumbling, rusting steel mill some mile down river, either reading a novel or watching television, I can’t remember. Suddenly, with absolutely no indication this would happen, I was utterly, totally, completely, and fully convinced of the following—the unity of all creation, the benevolence of that reality, the thrumming of a blessed energy beneath the universe, and most of all a genuine and infinite tenderness to all of my fellow suffering creatures, an empathy that for a second made pure adrenaline course through my heart, that left my mouth dry and my head dizzy. I felt, for a second, as if I was in the glorious presence of a kind and knowing and wonderful something.

For all that is mysterious about the heavenly choir…nothing is stranger than their goodness.

Now, normally I’m rather a shit. Which is why this uncharacteristically moving sense of togetherness with existence still remains so memorable to me. And I’m under no illusions as to the veracity of that experience, that divine “click” that suddenly moved in heart and spirit, soul and mind. No doubt there could be some recourse to material explanation, a kernel of dopamine that got loose in my synapses, some endorphins kicked up for a physiological reason. At that point I was a few months sober, and the reformed among us tribes of dipsomaniacs often speak of a so-called “pink cloud,” the heady rush of those first few months when you’ve dried out and you’re no longer bathing your nervous system in liquid depressant, so that the most basic of normal functions appears as if heaven to you. So, maybe, it was some random neuron flaring, just a bit of the cognitive flotsam that gets trudged up now and again, more often through chemical intervention, but occasionally through the sheer randomness of everything.

All of this could be true—and it strikes me as utterly irrelevant. Because whether or not that experience was just “in my head” misses the point of what perception is—everything is, of course, mediated through my head. The question is whether or not it corresponded to anything in the outside world, but when it comes to ecstasy and transcendence that very question strikes me as more of a category mistake than as anything that is particularly useful. Barbara Ehrenreich, the great muckraking journalist, writer, and thinker, had a not dissimilar experience when she was a thirteen-year-old girl in California, writing in Living with a Wild God: A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth about Everything how she suddenly realized that “it seemed astounding to just be moving forward on my own strength, unimpeded, pulled toward the light.” This was no Saul to Damascus moment to Ehrenreich, who was and remained an atheist her whole life, but it was an acknowledgement of an uncanny something. Reflecting on that moment, she writes that “You can and should use logic and reason all you want. But it would be a great mistake to ignore the stray bit of data that doesn’t fit into your preconceived theories, that may even confound everything you thought you were sure of.”

Because the situation is, whether they are “real or not,” people have long experienced angels, and still do. I’m envious, because I would love to see an angel, though I think that I’ve experienced grace, and that’s not necessarily a different thing. Often the word theophany is used to describe the divine encounter, the experience of something that is infinite and eternal, both immanent and transcendent, and far above our prosaic reality. The beauty of theophany is that such encounters happen in the real world, for where else would they occur? Mythopoetically, theophany is expressed through the narrative of angelology; such moments are personified as those winged and glorious beings who bear our faces but little else. Yet a curious aspect of angelology are the ways in which the word “angel” itself has degenerated in the public imagination in a manner that the phrase used to describe their fallen adversaries simply hasn’t. “Angel,” as a word, has shifted from connoting something mysterious and fearsome, awesome and terrifying, glorious and otherworldly, into pure maudlin kitsch. My suspicion is that there is a lot more leeway for those who believe in ghosts and specters, sprites and faeries, even demons, than there is to say that you believe in something as sentimental as angels. They are understood in our mass culture as gauzy, sugary, corny, schmaltzy. Pure, unadulterated, irredeemable schlock, the subject of awful religious broadcasting dramas and cheap porcelain figurines sold on cable television late at night to the credulous.

A disservice, a slander, a libel—for angelology as properly constituted has nothing to do with Touched by an Angel or Hummel Figurines. Angelology, rather, is the discipline which probes the ecstasies of transcendence, the ineffable nature of meaning that permeates reality in a space with which words themselves can’t fully grapple. Just because angelology reduces us to the wooliest of superlatives—“infinite,” “eternal,” “ecstasy,” “transcendence”—doesn’t mean that they don’t refer to that something, nor is it a reason to abandon angels themselves to the saccharine and the mawkish. Poet and folk musician Leonard Cohen, a consummately non-mawkish and anti-saccharine artist, a lover but not a sentimentalist, was asked in a 1984 interview by journalist Robert Sward of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation about his affection for the word “angel.” Detailing his attraction to the way the term was used by those great poets of beatitude Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso, Cohen admits that “I never knew what they meant, except that it was a designation for a human being and that it affirmed the light in an individual.”

This is a telling answer about the angelic, our attractions to them whether in Paradise Lost or It’s a Wonderful Life, the manner in which such beings reflect the divinity in humanity and the humanity in divinity. They are otherworldly, but near; alien, but familiar; pure alterity, and yet totally personal. Angels are the waystation between us and the unapproachable God. Cohen explains how the Beat poets were anything but maudlin in their attraction to the image of the angel; such a being to them wasn’t evidence of cheap faith, but rather of the connections between the suffering soul and something in the great beyond, a light in the perennial darkness. “An angel is only a messenger, only a channel,” Cohen says, and yet we’re angels to each other, for the “fact that somebody can bring you the light, and you feel it, you feel healed or situated. And it’s a migratory gift,” suggesting that angels themselves are as much verb as noun.

We feel a twinge of embarrassment at the angels. First among Christians, for whom angels were remnants of that pagan panpsychism which saw consciousness in the mossy trees and slick rocks, heard it in bubbling streams and blowing wind, and today they still endure as refugees in our secular world. They both attract and discomfort us. Angels have always been innately strange, obviously when depicted as completely foreign, perhaps terrifying beings, but arguably no stranger than when they look like us. Notable that angels have been present in the Abrahamic faiths from the very beginning, characters in the earliest of scripture, and that no attempts at reform have ever totally eliminated them. Within Christianity, every aspect of the faith has been challenged, every element of the Nicene Creed contested, but angels have never been exorcised, a mainstay as much among uneasy Protestants as among Catholics. Even for liberal Christians who see the angelic as metaphorical rather than literal (and those are dodgy and hard to separate categories), their endurance in the realm of the symbolic evidences their intrinsic attractions. They are exiles from the the age of enchantment which has supposedly long passed; they couldn’t be smashed by a Luther, explained by a Newton, or disproven by a Darwin, they endure even as belief in miracles declines, even as faith in God diminishes.

Max Weber, the great German sociologist of religion, argued in his 1918 Science as Vocation, that the “fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the disenchantment of the world.” If previous centuries, before the Industrial Revolution, before the scientific revolution, before the Reformation, or whenever you choose to date the crime, were endowed with a sense of glowing, numinous meaning, then today Weber would have us believe that we’re devoid of that purpose, that reality is now gray and ashen. Largely, I think, this is true. Except the angels still fly.

“Precisely the ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life either into the transcendental realm of mystic life or into the brotherliness of direct and personal human relations,” writes Weber. “It is not accidental that our greatest art is intimate and not monumental,” and yet the angelic is still explored in the most introspective and personal of expression, as well as in the gaudy hagiographies of memorization. Angels remains powerful symbols because angels remain powerful. Even their presence in the schlockiest of media speaks to their appeal, perhaps more so than any references to them in the rarefied avant-garde worlds of a Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Corso. Mock the little bed-side statue of a berobbed, behaloed, bewinged, and beharped child sold late night on QVC, ultimately, she remains a representation of the great I AM, of the connection between the profane and the sacred, of Jacob’s infinite ladder with its tumbling angels forever ascending towards paradise. “Every angel is terrifying,” writes the poet Rainer Maria Rilke in The Duino Elegies, and he’s right.

Both that which appeared to Ezekiel in the desert imploring him to be not afraid and the little figurine are terrifying, but beautiful as well, for what they embody and represent are that sacred and forever distant world of meaning that for a few brief moments sometimes intercedes into prosaic existence. Cohen’s observations about the prevalence of the word “angel” in the radical poetry of the Beats (and in his own work) speaks to something which creative artists have always known—that this something always shimmers a bit when engulfed in the process. Creative acts—painting and dancing, music and writing—are so often where that enchanted conduit to the transcendent remains obvious. It should be pointed out that so often the miracle of angels is a literary one; the being that commands Ezekiel to eat a scroll rolled in honey, making those words part of his flesh; Gabriel appearing to the Prophet Muhammad with the perfection of the Qur’an; Moroni with Joseph Smith and those Golden Tablets of Palmyra. Angels are writers. And dancers. And musicians. And painters. And sculptors. They endure because they are such a perfect encapsulation of the mysteriousness that still defines creation, that can’t be entirely explained away by neurology or sociology. They are as if what Federica Garcia Lorca called the duende.

The structure of reality, those visions of heavens in the stumps of fallen trees, are visions of goodness.

“It would be tempting to reach for a universal definition that could apply across all these cultural settings,” writes Valery Rees in Gabriel to Lucifer: A Cultural History of Angels. Supernatural beings or cultural archetypes, transcendent creatures or poetic symbols. Or somehow all of these things? Rees writes that if “we wish to consider the idea of angel as a psychological archetype we must first decide whether we are considering a simple messenger, a protector, a concept of goodness, a motivating idea, or a soul free from bodily form. For angels fulfill all these roles.” Their variability is certainly part of what makes angels so evocative still, but Rees’ identification of “goodness” as being one of their most important attributes can neither be skirted over or sandwiched between other roles of such beings. Goodness, after all, is one of the most operative connotations of the very word. “You’re an angel,” “Be an angel,” “She was an angel.”

For all that is mysterious about the heavenly choir—their behavior and appearance, their function and their agency—nothing is stranger than their goodness. It remains the great scandal of the angelic, arguably the great scandal of ethics. In our bloody and wicked century, inheritors of the monstrous twentieth-century, nothing can seem more foreign, and irrational, than goodness. To be good is to not act in self-interest, it’s to reject the instrumentalization of other people, it’s to recognize someone else beyond the veil of culturally and economically enforced solipsism. Goodness remains radical, it remains strange, and yet it’s very much real. By making angels symbolic of goodness, there is a union of metaphysics and ethics, so often kept philosophically distant, and yet intrinsically connected. To say that angels are symbols of transcendence and of ecstasy must not be purchased with an ignorance of goodness, for such mystical reveries are only masturbation unless they also acknowledge the idea of goodness, the idea of the sanctification and sacredness of other consciousnesses.

Religion is sometimes situated—not entirely consciously—as riven between the metaphysical and the ethical, between questions of ultimate meaning (“What is reality? What is the universe?”) and issues of how we best take care of one another (“What does it mean to be a good person? How do I best care for my fellow humans?”). The brilliant Chicago-based alt-country band the Handsome Family, composed of wife and husband Rennie and Brett Sparks, whose lyrics often touch on the gothic and the mad, describe this dichotomy in the spiritually aptly titled song “Weightless Again,” off of their 1998 album Through the Trees. Brett asks in the song “which is more important/To comfort an old woman/Or see visions of the heavens/In the stumps of fallen trees?”

That’s always been the two vocations of the spiritual; to be mendicant, anchorite, mystic, ascetic, stylite, or rather to work as the missionary, the cleric, the evangelist, the healer, the saint. What angels suggest is that as properly understood, these are all the same thing. The structure of reality, those visions of heavens in the stumps of fallen trees, are visions of goodness. If they are intuited properly, understood properly, reverenced properly, then it’s not a question that you will comfort the old woman. To comfort the old woman in hopes of reward, in desire of heaven, is, of course, not to really do good at all. Rather what angels as conduits of pure goodness threaded throughout existence function as is a symbolic reminder that we do good not because of the punishments of heaven and the pleasures of hell but rather because to do good is an inviolate law of reality, as real as gravity. A command not in reference to some instrumental bottom line, but an end unto itself. The entire, utter, and total whole thing.

__________________________________

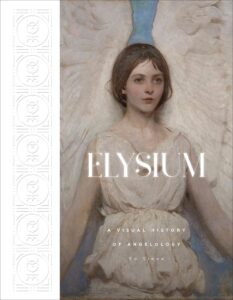

Excerpted from Elysium: A Visual History of Angelology by Ed Simon. Copyright © 2023. Available from Abrams Books.

Ed Simon

Ed Simon is the Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and the editor of Belt Magazine. His most recent book is Devil's Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, the first comprehensive, popular account of that subject.