This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

I have a lot of bad ideas. For instance, remember way back when I started this essay by saying I have a lot of bad ideas? That was probably a bad idea.

I bring up my bad ideas because the act of writing satire — something I do between stretches of deciding whether I’ll ever write again — hinges on the patience to discern bad ideas from ideas that really work. But this raises two questions: 1) What does it mean when a piece of satire writing “works?” and 2) If a piece of satire “works,” should it look into unionizing?

To answer the former and, like any great leader, ignore the latter, let’s start off with two simple rules: 1) There are many ways to write satire, and 2) There is also only one way to write satire.

To make sense of those diametric statements, I will invoke the philosopher Albert Camus while using the word “diametric,” so that I might sound like I know what I’m talking about. In short, I believe it is the job of satire “not to be on the side of the executioners.” Or, rather: If satire is on the side of the executioners, it is not satire at all. And so long as satire is not on the side of the executioners, it can be anything. Although it really should be funny.

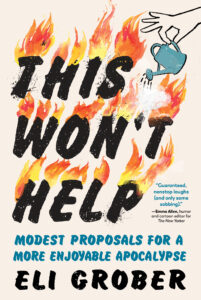

Satire dances on a knife’s edge between comedic commentary and complete disaster. To that extent, I’d like to speak to the origin of a specific piece in my forthcoming essay collection, This Won’t Help: Modest Proposals for a More Enjoyable Apocalypse.

One day, not too long ago, I found myself barricaded in a supply closet during a shelter-in-place as a gunman was on the run near the building where I work. We had very little information from the outside, but I had cell service. (I will not name the provider, as I don’t do unpaid promotions. Reach out, young wireless reps!)

The group I was hiding with and I were all texting with our families. I decided to try and tune in to a local police scanner to get more accurate information. I found one, and when I went to play it, I was forced to listen to a two-minute ad. Perfect — American capitalism at its finest.

A couple hours after it began, the shelter-in-place ended. Nobody in the building was hurt, and now it’s almost as if nothing ever happened. But that day, after leaving that closet, I couldn’t sit down for hours. My adrenaline was at an all-time high. I sat with the experience for weeks—and eventually found release in writing a piece for my book called “Thank You for Calling the Active Shooter Hotline. There Are [EIGHT] Customers Ahead of You in Line. Please Enjoy This Message from Our Sponsors.” As a means of getting my head back after that incident, writing that piece did, at least a little bit, help.

Satire is a reaction to being alive and aware of the world at-large. And because history tends to repeat, satire sometimes feels like a prediction — months, years, decades, even centuries after it was written. Satire can speak truth to power. It can be a defiant act. It can deliver new ways of thinking about the world. It can reinforce community and remind people they’re not alone. But at its core, it is catharsis. It is an immediate and tangible way to grapple with the hardness and weirdness of life and of being a human.

In many places around the world and at many times throughout history, writing satire could get you banished from society — or, worse, a job in politics. Luckily, so far, I have avoided both of those fates. And I feel fortunate to live in a time and a place where I can write something like the above chapter in my book and be relatively confident that I will not be forced into exile. But we’re certainly headed in a direction that makes me less confident every day that a book like mine won’t be banned or, turning Bradbury into Nostradamus, burned. Perhaps that’s how you know a piece of satire really works — when it’s been set on fire.

It’s often said, in our age of absurdity, that satire is dead. It died when Kissinger won the Nobel Peace Prize. Or it died with Trump. Or it died yesterday, suddenly, in its sleep, and we’re just barely too late to revive it. Sometimes I try to stop writing satire altogether. I think to myself, I should just write a movie in which Tom Cruise has to run somewhere. That would do well. Who do I get in touch with about that?

But then I put pen to paper. Or, much more often, fingers to keyboard. And, of course, much less often, quill to parchment. And when I do that, even when I’m writing in new structures or longer works, I find it almost impossible to center my writing — if only by way of a subtle nod — anywhere other than satire.

Out of curiosity, I googled the word “satire” before writing this essay. Now’s a good time to remind you that I have a lot of bad ideas. For instance, it may have been a bad idea to tell you I googled something to write these final paragraphs.

In my ensuing search, I found that among ancient humorists like Aristophanes and Zhuangzi, one of the earliest and most explicitly satirical collections was written by a Roman poet named Juvenal who lived about two thousand years ago. (I say all this, once again, to look like I know what I’m talking about.) It turns out Juvenal had the same disease I do, since my google search told me he once wrote the following, roughly translated:

“It is difficult not to write satire.”

Some things never change.

_______________________________________

This Won’t Help: Modest Proposals for a More Enjoyable Apocalypse is available now via The Experiment.