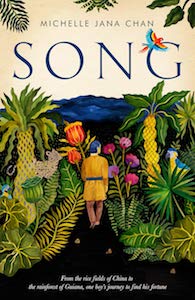

Too Close To Home: Writing a Book That Your Parents Won’t Read

Michelle Jana Chan on the Power of Family to Shape Your Own Narrative

I remember this journey so well:

Morning slowly colored the dark river. The depthless water lightened to a pearly grey. The smudge of trees began to create patterns of green. On the bank a family of capybara came to drink, their coarse hairs silvery through the layer of mist. They lapped at the water, eyeing the narrow boats that glided past. Above, a lonely indistinguishable stork sailed against the light. Song felt like he immediately belonged to this mystical place he’d always called “upriver.”

Not exactly this journey, which is a fragment of fiction lifted from my novel. But the description was based on a real boat journey I took with my dad up the Demerara, one of the great rivers of Guyana, where the forests feel vital, harboring multitudinous but largely unseen wildlife, and the giant trees growing are monumental.

The trip to Guyana had been more than a vacation. This South American country—the setting of most of my debut novel—happens to be my dad’s homeland, my heritage. This boat journey took place on my first ever visit, and a return for him after several decades of absence. The adventure prompted me to write Song. As I put down this passage of the book, years before it was published, I imagined my dad reading the words one day, bringing the book to his chest, holding it close as he recalled our trip together.

It would not only be the book’s geography that would be familiar to my dad. The story was loosely based on family history, the details of which remain elusive to us. In the post-slavery era, when colonial powers needed cheap labor to replace free labor, they lured their subjects around the world with the promise of a better life; we would have had forefathers caught up in those mass migrations of the late 19th century.

I wrote Song because I wanted to tell the story of that moment in history in that particular part of the world. I had a kernel of a fictional tale germinating, and as a journalist, I had long wanted to take on a long-form project. But perhaps, above all, the most compelling reason to write this book was for my dad to read it.

Except he never has.

I remember allowing myself a stab of pride when I told him about my book deal. When Song was published in hardback, he bought several copies. He sent out an email to his friends with an online bookstore link. At the launch, he told me how impressed he was with the generous speech by my publisher, John Mitchinson, founder of Unbound, who had said it was “not only an excellent book, but an important book.”

In the months that followed, I received feedback on Song from unknown readers. Some had questions, some had praise. But I heard nothing from my dad. I noticed the copy of Song on his bookshelf appeared uncracked. His silence was stinging.

One day, I asked him directly if he’d read my book. Not sharply, not accusatorily.

He hesitated. “No.”

I had suspected as much, but I was still taken aback.

“Oh,” I said. “Why not?”

He paused. “It feels a bit close.”

A part of me wanted to scream: “It’s fiction! It’s set over 100 years ago! I made it up!”

Instead, I said, absurdly gently, craving approval: “I’d like you to read it.”

“Okay,” he replied. “I will.”

As much as I didn’t want to make excuses for him, I conceded to his point that it might feel close. Close to the bone, I think he meant. The subject matter addresses issues that our family has been forced to confront as a minority: colonial history and morality; the intersectionality of race, class, and gender; identity and belonging. Yet isn’t that the rub of life, of fiction? And wouldn’t those be reasons to read a book, not resist it? For the echoes, the trigger of memory, for the resonance and unearthed pain.

I berate myself now for letting the book be shaped by him, by my musings on how he might feel when he read it. I included his favorite foods: roti and curry, pine tarts, crab backs; the taste of pepper pot, like my grandmother used to make it. I paraphrased bedtime stories he once told me, inserting them as tokens of affection: “He remembered the tree where he had hit a gecko with his slingshot and cried himself to sleep that night; the canopy where he had sheltered from the rain and was so late home Amalia walloped him… ”

Also, excruciatingly, as a woman pushing 50 years, I found myself cutting or toning down sex scenes after I landed the book deal. Envisioning my dad with a newly published book in his hands, I edited out some of the details. (Some might not believe me, as there’s still plenty contained, from Song losing his virginity, to underage sex, to paid sex, to rape, to adulterous sex, to incest).

I also named characters in the book after members of our family, as an homage. Most were long passed, such as Flo, his beloved grandmother, for whom I named the purposeful young woman who appears towards the end of the novel. Enthusiastic readers have asked if I will be writing a sequel with Flo as the protagonist. But not my dad. He doesn’t even know that there’s a Flo in the book.

I berate myself now for letting the book be shaped by him, by my musings on how he might feel when he read it.

I sometimes wonder what he says when people ask him what he thought of his daughter’s debut. Does he admit to never having read it? Or does he just gloss over the question? I don’t completely rule out that he has read Song and couldn’t bear to tell me he hated it, but he’s the honest sort; I think he would have said so.

When I confided in a friend, the author of a dozen or so books, that my dad hadn’t read Song, she shrugged. “My parents haven’t read my books either. They’re on their coffee table in the living room, but they haven’t read them.”

“None of them?” I asked incredulously. “Don’t you care?”

“Not really. They’re not really readers. They like to show them off to their friends, but that’s about it.”

But my dad is a reader. He chooses to read other books over mine. Does that burn? Yes, it burns.

“Let it go,” my friend advised.

*

Before I wrote this piece, I felt I should ask my dad one more time—in the name of research—if he’d read Song. After all, it’s not like he hasn’t had time, with a pandemic raging, to sit on the sofa and pick up a book.

Of course, I knew the answer before he opened his mouth. I hear the echo of my friend’s counsel: let it go. I’m trying to, but I can’t help but hope he’ll one day take Song down from his shelf, leaf past the dedication to him and our family, turn to the first chapter and begin.

Since Song, I’ve struck a publishing deal for my second book. It’s contemporary; it opens around 9/11 and spans 40 years, speculating two decades into the future. The story is about a friendship between two women. Surely this subject matter won’t be “too close.” I do explore themes that will make my dad feel uncomfortable, just like in Song, but that friction, that torment, is nothing more than a reason for literature’s very being. So, why is it my book is too close? Perhaps because it’s my book, that his “too close” excuse isn’t about geography or identity, but his and my closeness. The bond of a parent and child, there’s nothing more inextricable; it can, in fact, be too much to bear. And if it is that closeness he meant, then perhaps his choice to leave my book unread is entirely natural, and only human, and I can finally let it go.

__________________________________

Song is available from Unbound. Copyright © 2021 by Michelle Jana Chan.

Michelle Jana Chan

Michelle Jana Chan is an award-winning journalist and travel editor of Vanity Fair in the UK, where she presents the magazine’s digital Future Series. Formerly, Michelle was a BBC TV presenter, news producer at CNN International, and reporter at Newsweek. She was a Morehead-Cain scholar at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her fiction debut, Song, is out now from Unbound. @michellejchan