The young Mrs. Rimon had approached him fleetingly as they were leaving the synagogue, and had asked him for a private meeting. “I’d like to bring my son to you,” she’d said hurriedly, under her breath. Rabbi Bonfiglioli had been a little surprised. He seemed to remember that the boy was just a kid, certainly not old enough to be preparing for his Bar Mitzvah. In any case, the Rimons were nothing special. They were a good family but they were not particularly observant; tepid at best. Sure, they came to services en masse for the obligatory festivals—Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur—always with a motley gang of relatives in tow, but that was it. He had seen the mother there on her own every now and again, always in a newly-tailored dress, but she looked more like a polite spectator than a woman of fervent faith. There was one thing that had caught the rabbi’s interest, however: the prayer book she clutched in her hand. The print looked ancient and the cloth binding with big floral patterns on it was well worn. He would have paid anything to be able to take a look at it, but he didn’t know the woman well enough to ask. “I wonder whether she’ll bring it when she comes to the appointment?” He only allowed himself to indulge in frivolous thoughts of this kind on the Sabbath.

The boy was more or less as he remembered: a bright-looking child who was not even remotely intimidated by the heavy furniture that made his office so oppressive. Imagine, the rabbi himself sometimes had to step out of that room in order to lift his spirits a little; even if only to dive into the corridor.

Without waiting to be invited, the boy sat himself down in a low chair next to his mother. The gesture was entirely natural, without a hint of arrogance. It was as if he were already conscious of the fact that—wherever he was in the world—there would always be a place for him.

“What’s your name and what grade are you in?” That was the script, and Rabbi Samuele Bonfiglioli was not about to alter it.

His name was Alessandro. He only used his full name; he didn’t like nicknames and neither did anyone else in his family. He was eight years old, and this coming October he would be going into fifth grade.

The rabbi was bewildered, again. The script was not right.

“Fifth grade at eight?” he asked.

“Yes, but I turn nine in February.” The boy seemed apologetic. “I’m two years ahead,” he murmured quietly, almost inaudibly.

“Good lad,” Rabbi Bonfiglioli answered mechanically, while his thoughts were beginning to wander.

Why had he been asked to meet the child? He remembered something he had heard through the grapevine about a Jewish boy—a little genius—who had skipped a couple of grades in public school because he’d already learned everything on his own.

What does a rabbi have to do with educational acrobatics of this kind?

He had better things to do. His task in life was to study the Torah and pass his knowledge on to the next generation. Getting boys ready for their Bar Mitzvah was his calling. When his eyes chanced upon a pupil’s expectant gaze, the joy made his heart miss a beat.

There was a long silence. The boy rocked in his chair and then got up to observe the furnishings and objects in the room. It was as if he were taking ownership of them. The rabbi could see that his curiosity had been fired by the heavy brass paperweight on his desk, a globe held up by four muscular figures, which was actually an inkwell filled with black ink. He was, indeed, fascinated. He wondered whether the powerful figures might be Cyclopes but then decided that, given they were in a rabbi’s home, they had to be replicas of Samson.

“Rabbi, Sir.” Emilia Rimon was hesitantly trying to start a conversation. “I asked for an appointment because I needed to ask you a question.” Her son, the boy in front of him, had announced a few days earlier that he only believed in God sometimes. “This seems like quite a serious matter for a Jew, don’t you think?” she added hastily.

Rabbi Bonfiglioli wasn’t at all keen to answer. The woman’s fumbling attempt to reel him in had not been effective. She didn’t look like a woman who was overflowing with religious zeal. Apart from anything, she hadn’t even brought the prayer book he had been so interested in. Her tentative question felt like a pretext she had hurriedly pulled out of thin air. The vague impression that he had had on their first encounter must have been correct, after all.

Emilia Rimon was simply driven by an irrepressible urge to show off this child prodigy: a boy who was so intelligent that he had become the family’s pride and joy. Somehow, though, the idea that the legend of this brilliant kid might somehow have already reached the ear of the Chief Rabbi of the entire Genoa community tormented him.

Was he supposed to answer the woman’s spurious query? The rabbi was an uncomplicated kind of person, a teacher who loved the Torah. Nothing more. The kind of maxims some of those “wonder rabbis” might come out with—false prophets and preachers all—were simply not his thing. He was one for straight talk, and preferred those humble words which had been handed down since the beginning of time. Soon, however, before he was even aware of it, he felt his irritation dissolve into a wave of indulgence. This was the way it always went. Human weakness ended up moving him.

“Good boy,” he said, in a tone of voice that was so bland it could have been used in any number of situations. “I understand that you like learning. It will soon be time for you to study the Torah.”

Then he bent over the boy and whispered in his ear, “You say you only believe in God sometimes. You should know, though, that God believes in you always.”

*

Alessandro hadn’t wanted to go to the rabbi; it was his mother who had dragged him there against his will. Now, however, he had to confess, that phrase the old man had spoken into his ear struck him as beautiful.

Perhaps even true.

*

It felt as though Marc had been lurking behind the front door waiting for them. He opened it wide before his wife had time to put her key in the lock.

“You took Alessandro to the rabbi? Why would you do that?” he asked, as soon as they came in. He had had no idea; it was Nonno Luigi who had told him.

“Well,” Emilia improvised, “I realized the rabbi had never met our son. Alessandro never comes to synagogue with me on the Sabbath.”

“That’s because he’s at school on the Sabbath!” Marc shouted, no longer bothering to hide his irritation. Then he stopped suddenly, turned on his heels, and strode out of the house setting off for the laboratory. His wife was always so harsh with him; there was really no need to stoke the flames.

__________________________________

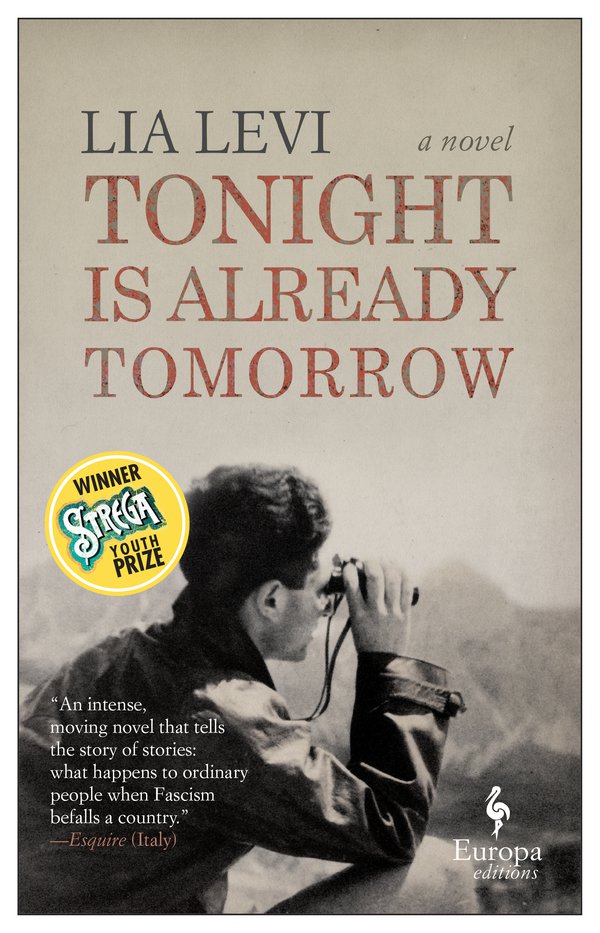

Excerpted from Tonight Is Already Tomorrow by Lia Levi, trans., Clarissa Botsford. Excerpted with the permission of Europa Editions.