Toni Morrison is More Hemingway Than Hemingway Himself

On Adverbs: Is Less Really More?

Though it’s long been received literary wisdom that adverbs should be used with a more-is-less approach, an in-depth look* at hundreds of canonical titles—sourced from assorted “Great Books” lists—shows us that the standout books indeed rely on fewer adverbs. And even within each author’s own works, the books that use the least adverbs have been the most successful.

But there was one more question on my mind: What about the rest of us?

Before I’d be satisfied, I wanted to find out how great writers compare to the average writer when it comes to adverb use or abuse. Do Hemingway’s “laws of prose” apply across the whole of the literary universe, from the award winners and bestsellers to the amateurs? I set up one final showdown to find out.

I downloaded more than 9,000 novel-length fan-fiction stories (of 60,000-plus words) from fanfiction.net. This would be my “amateur” group, consisting of all stories written between 2010 and 2014 in the 25 most popular book universes (ranging from Harry Potter to Twilight to Phantom of the Opera to Janet Evanovich’s books). People writing stories this long are committed to their work, and many of them are strong writers. But on average, they’re not at the level of the bestsellers or the award winners of the literary world. So I compared the fan-fiction sample to all of the books that have ranked number one on the New York Times bestseller list since 2000, and also to the 100 most recent winners of major literary awards.*

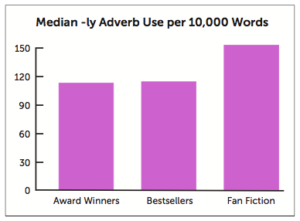

When set side by side, the difference is clear. The median fan-fiction author used 154 -ly adverbs per 10,000 words, which is much higher than either of the professional samples. The 300-plus megahits in the bestseller category averaged just 115 -ly adverbs per 10,000 words. And the 100 award winners have a median of 114 -ly adverbs. It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison, but the novels that sell well in bookstores come in with 25% fewer adverbs than the average novel that amateur writers post online. Less than 12% of all number one bestsellers had more than 154 adverbs, even though half of all fan fiction does.

The results of this chapter are one half common sense and one half mind-blowing.

Most writers and teachers will tell you that adverbs are bad. This is not a controversial stance to take. In many ways, the statistics presented above are just a confirmation of what we already knew.

But the fact that their use is somehow correlated with quality on a measurable level—even when just the best writers are being examined—is still shocking. It might not be a surprise that some beginner writers use adverbs as a crutch more often than professional writers, and that these traits may sometimes be noticeable. But even when looking at the life’s work of the best writers, the effect is present.

A statistical correlation, of course, does not imply causation. Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby used 128 adverbs per 10,000 words while his lesser-known The Beautiful and Damned used 176. If you picked up The Great Gatsby and stuck in 200 more adverbs, a bit less than one a page, it would have a higher rate than The Beautiful and Damned. Would this version of the book still be celebrated? What if you trimmed down the adverbs from The Beautiful and Damned? Would Leonardo DiCaprio be ready to suit up for the role of Anthony Patch?

The answer of course is that it’s not so simple. Adverb rate alone could not have such a direct impact on the success of a book. There are thousands and thousands of other aspects of writing in play. The Hemingway adverb stereotype may be true, but there are notable counterexamples—authors who have written successful books when increasing their adverb usage. Nabokov’s Lolita, for instance, has more adverbs than any of his other eight English novels.

One possible explanation for the overall trend we’re seeing is that adverbs are an indicator of a writer’s focus. An author writing with the clarity needed to describe vivid scenes and actions without adverbs, taking the time to whittle away the unnecessary words, might also be spending more time and effort making the rest of the text as perfect as possible. Or if one has a good editor, these words may be weeded out.

The “focus” hypothesis finds some support from the true master of writing without adverbs. And it’s not Hemingway.

The numbers revealed an overlooked champion. Combing through a large number of authors, there was but one author on the list of “greats” who outdid Hemingway: Toni Morrison. She may be a Nobel and Pulitzer Prize winner just like Hemingway, but her place at the height of concise writing isn’t often cited in English classrooms. Her adverb rate of 76 edges out Hemingway’s 80, and puts her well ahead of others like Steinbeck, Rushdie, Salinger, and Wharton.

Morrison has said in multiple interviews that she doesn’t use adverbs. Why? Because when she’s writing at her best, she can do without: “I never say ‘She says softly,’” Morrison tells us. “If it’s not already soft, you know, I have to leave a lot of space around it so a reader can hear that it’s soft.”

There you have it. And while I have no hard evidence that the logic of adverb usage carries over to wacky statistics-based prose, I went through the text of this chapter to search for -ly adverbs after writing 5,000 words on how awful they were. I found that in most cases they were unneeded. They often blunted the impact of my sentences. I deleted all -ly adverbs that were not used when quoting or citing others.

As a result, if you excuse the ones in quotes, you will find no -ly adverbs in this chapter. This makes for a usage rate of 0 per 10,000 that would rank this text ahead of (or tied) with all other texts ever written. Does that make this chapter, regardless of content, a step above average? Here we’ve found the limits of our statistics. But when trying to write standout prose, it can’t hurt to deliberately avoid the troublesome part of speech.

*As shown in the first chapter of Nabokov’s Favorite Word is Mauve.

From Nabokov’s Favorite Word Is Mauve: What the Numbers Reveal About the Classics, Bestsellers, and Our Own Writing by Ben Blatt. Used with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright 2017 by Ben Blatt.

Ben Blatt

Ben Blatt is a writer and statistician. He is the co-author of I Don’t Care if We Never Get Back and the author of Nabokov’s Favorite Word is Mauve.