Tom Verlaine was the Strand’s Best Customer

Booksellers Remember the Coolest Celebrity “Cart Shark” of Them All

Every bookstore has regulars, but no bookstore has such a wide and eccentric cast of recurring characters as New York’s Strand. To work there, as I did for one memorable year, is to know them: the sellers, the hagglers, the unyielding optimists checking in at the information desk for the esoteric titles they requested over a decade ago. The guy who checks out five minutes before closing every week with 70 paperbacks, or the ambiguously arty-looking person who comes in at the end of each month to sell old monographs to make rent. But no regular was as consistent or beloved as the punk-rock legend Tom Verlaine, the patron saint of the dollar carts, who died after a short illness on January 28.

Verlaine was best known as the guitarist and vocalist of the band Television, whose short run in the ‘70s influenced generations of acts from Joy Division to the Strokes. Following his death, critics have praised the way his sensitive guitar work shaped the punk scene and music at large. His friend, collaborator, and one-time lover Patti Smith wrote a remembrance for The New Yorker.

In addition to his musical legacy, though, Verlaine was a fixture in a small corner of the New York book world. Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore pointed to it in a tweet:

Went by the book stalls outside Strand yesterday thinking I’d see you as usual, have a smoke, talk about rare poetry finds for a couple of hours, downtown NYC racing by our slow meditations on music, writing – gonna miss you Tom. TV Rest In Peace.

— Thurston Moore (@nowjazznow) January 28, 2023

Article continues after advertisement

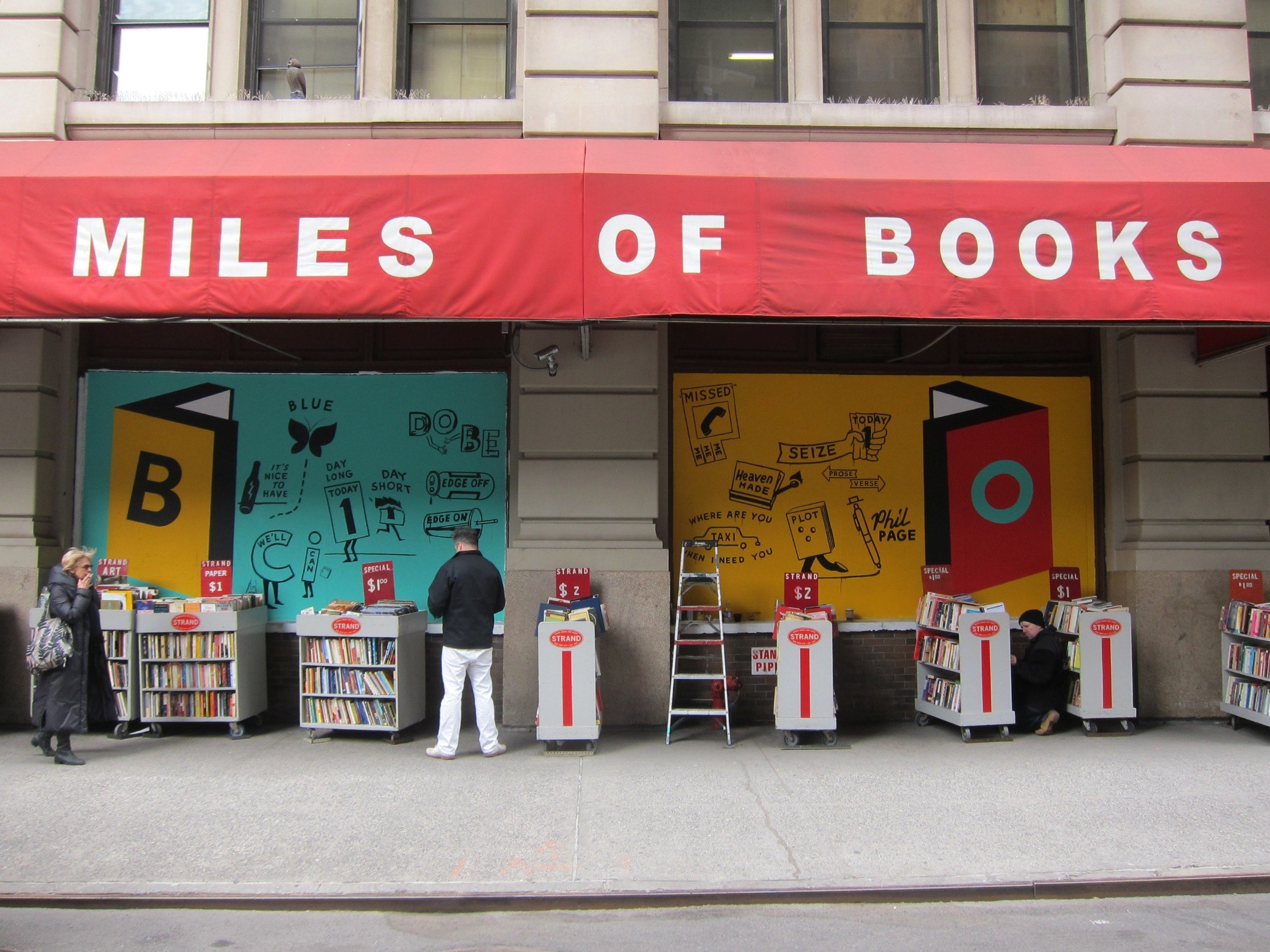

Moore isn’t alluding to some kismet encounter between rock stars in the street. If you swung by the carts that line the Strand’s exterior, where all the books cost $1-5, odds were good that you’d run into Verlaine, searching for grails that had been shunted out to the street. “Pre-COVID? He was there every day. For at least an hour or so,” said Peter Calderon, a Strand employee of more than 15 years. A former employee, Alice Richardson, described him as most employees remember him: “He’d be quietly browsing the dollar carts at night, smoking in an overcoat.”

Strand and Verlaine had a long history. He was one of the store’s most famous alumni, along with Smith, fellow Television founder Richard Hell, and Sam Shepard. When the store’s owner Fred Bass died in 2018, Verlaine eulogized him for the New York Times. But his gig in the shipping department was just a blip compared to his decades-long tenure as unofficial Carts Captain.

“Everyone who worked there knew he was a regular,” said Christopher Pirsos, another former bookseller. “I don’t think he ever bought a book from inside. He almost exclusively bought cart books.”

Among the Strand regulars, the cart-exclusive customers are an especially fierce and quirky breed. Employees have a few different nicknames for them, some more flattering than others, but “cart sharks” is a classic that captures their spirit. They’re bargain hunters, emphasis on “hunt.” Some people bring URL scanners to quickly run ISBNs and see if they can flip a book on Amazon. Others are less interested in value and more excited by the prospect of finding a diamond in the rough. Verlaine was definitely the latter. More importantly, he was a bridge between the cart sharks and booksellers who hauled out fresh books to feed them.

Calderon saw the way Verlaine influenced the carts firsthand. “That dude was awesome,” he said. “He innovated the way we work on the carts.”

“Whenever there would be a little empty space on the carts, he’d move the books over and fill up that area to create a bigger space. It was a way of letting the people know inside, ‘Yo, you got space, bring stuff out.’ It was Tom who started doing that, but after a while everyone else started doing it too.”

Whether or not Verlaine was the first to do this, it’s definitely telltale cart shark behavior that persists today. If you swing by and see someone clearing off shelves to make room, don’t get in their way, they’re a pro. Not all employees love this (I didn’t, it made more work) but Calderon finds it helpful. “For everyone working on the carts, it made their job so much easier. Because now I know I have this much space, I can bring out this many books.”

In addition to clearing space, Verlaine kept the peace and cultivated the vibe. “The cart sharks, the people out there looking for their money, a lot of them get aggressive,” said Calderon. “Tom was always cool. He always made it a point to not be annoying to whoever was working.” He was friends with other regulars and always willing to point towards an interesting find.

Not that he was never pushy. “Every once in a while, you’d be putting books out there, and he’d hover just behind you, waiting, super hyped,” said Pirsos.

But even if he was pushy, you didn’t care, because it was him. He was a bona fide rock star, and better yet, he was nice. Garrett Karrberg, another former employee, remembered encountering Verlaine for the first time. “I was doing carts and someone told me that it was Tom Verlaine out there and I didn’t believe them. Like, there was no way.”

But it was true, he was there, you could talk to him. Not everyone did, but if you wanted to, he was approachable. He would make small talk with people about back pain and movies, and, of course, books. He didn’t really talk about music, and almost never about himself. If he did, it was only in the most oblique way. “He’d be gone for a long time and you’d be like, ‘Oh no, did something happen to him?’” said Karrberg. “Then he’d come back and say ‘Oh I was on tour in Australia with my band.’”

What did he read? It feels indiscrete somehow to reveal a person’s book shopping habits, but Verlaine’s taste was so varied that it feels impossible to give anything away. He was seemingly interested in everything. He gave an interview in 2006 to Dusted Magazine (at Strand, naturally) where he namechecked some real deep cuts: a spiritual biography of Beethoven from 1927, a collection of Zen texts, Ananda Coomaraswamy’s Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art. “He would buy weird math textbooks and Japanese books,” Karrberg said. “He always wanted stuff in Japanese.”

It feels indiscrete somehow to reveal a person’s book shopping habits, but Verlaine’s taste was so varied that it feels impossible to give anything away. He was seemingly interested in everything.

A better question, maybe, is what the hell he did with all the books. He must have accumulated thousands, maybe tens of thousands, over a lifetime of cart-scouring. At the time Karrberg wondered about it. “Did he keep all these books? Does he read ‘em? He’s here all the time so he doesn’t have that much time to read them.” In the Dusted interview, he mentions a storage locker and occasionally selling off a box or two, but whatever drew him to Strand every night, it was not a financial project. “It wasn’t like he cared about the value of the book. It was always something that was interesting to him,” said Karrberg. “Like the math textbook, he was looking at it.”

The simplest explanation seems the best. He just loved books. “There’s no obsession with ‘books’ per se,” he told Dusted, but I (and probably anyone who ever encountered him at Strand), would beg to differ. He picked through the carts with such obvious care and curiosity that many booksellers recognized in themselves.

That was the secret, I think, of what made Verlaine so special to Strand. The store sees plenty of celebrities and notable New Yorkers, but no one came up through it and remained so deeply entwined with it like him. If you worked there, you got to see him nearly every day, talk about poetry with him for a minute, and wonder, for just a moment in the back corner in your mind, if you could become him—maybe not a full-blown icon, but someone so effortlessly cool, comfortable, and immersed in a life of words and music. Or maybe he’d just ask you to bring out more books

I only have one real memory of Tom. I had moved to New York from Illinois for an internship that went nowhere, and passed Strand’s little matching test to land my first job in the city, slinging fiction on the first floor and working the registers. Someone pointed Verlaine out to me early on (my manager Cale, I think) with a nudge— “You know who that is?” I did. Mostly I tried to stay out of his way, and I certainly didn’t try to talk to him.

One night though, as we were coming on closing time, he came in from the carts and the cigarettes to my register, wearing his usual overcoat. I said hello, trying very hard to seem casual. “How’d you do out there?” or something like that. He shrugged with a smile and slid the results of an hour’s searching across the counter: a small, old book of Buddhist poetry and a gardening manual, $3 worth of books in total. He paid in cash, and that was it.

Really it was nothing, but I remember in the moment thinking, “You’re here. You just sold Tom Verlaine a gardening manual. Things are okay.”

Things have not felt okay at Strand of late. The store has suffered many hard losses in the past five years. Fred Bass is gone, and Ben McFall, the veteran bookseller who was like a father to generations of booksellers, died at the end of 2021. The pandemic brought layoffs, and the employees still there feel unheard and unsupported by management. Tom Verlaine wasn’t an employee of the Strand, but he felt like a part of it, and his death marks another loss for a beloved but beleaguered New York institution.

Most of all, I’m sad for the carts. Verlaine was the human embodiment of what makes them special. You can’t expect to find anything in particular, but if you look hard and often enough, you’ll find something—or someone—extraordinary. The bargains will be there and the sharks will still be in the street, but Verlaine won’t, and it will never be the same.

Colin Groundwater

Colin Groundwater is a writer based in London. His work appears in GQ, Vanity Fair, and Highsnobiety.