Tom Bissell Talks Hollywood, Adaptation, and Feeling Like an “Actual Writer”

The Author of Creative Types Speaks With Jane Ciabattari

Tom Bissell has built a career on being a master of the literary pivot. He has written eight books of nonfiction (including The Father of All Things: A Marine, His Son, and the Legacy of Vietnam, in which he and his veteran father return to Vietnam together, and The Disaster Artist, co-authored with Greg Sestero), countless features, essays and cultural criticism for magazines like Esquire, The New Yorker, Harper’s, The New York Times Book Review, and The New Republic; video games (Gears of War: Judgment, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, Battlefield Hardline), books about video games (Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter, The Art and Design of Gears of War), and the 2021 TV series, The Mosquito Coast, based on the Paul Theroux novel. Talk about versatile.

But he is, at his core, an off-the-beaten-path writer of short stories that transmute human behavior into strange yet familiar moments. “The short story seems the right form for him,” Pankaj Mishra wrote in a NYTBR review of his first collection. God Lives in St. Petersburg: and Other Stories (2005). “…Bissell reveals himself to be not only a subtle craftsman but also a mordant observer of a new generation lost in a complex and dangerous world.” Two of the six stories in that first collection inspired films. “Aral” was the basis for Werner Herzog’s 2016 eco-thriller Salt and Fire, which spurred critics to engineer phrases like “mealy-mouthed mini-chamber piece,” “vast, impenetrable reams of aphoristic waffle,” and “the worst film Werner Herzog has ever made (but it’s still kinda interesting).” Bissell’s story “Expensive Trips Nowhere” became The Loneliest Planet, the highly regarded 2011 indie film about a couple backpacking in the Caucasus Mountains, scripted and directed by Julia Loktev and honored with multiple film festival awards, including the Grand Jury Prize at the AFI Fest in Los Angeles,

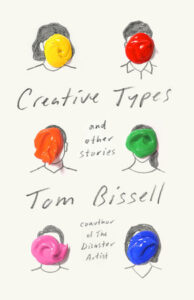

Bissell again shows his transformative genius in Creative Types, his second collection. “I do a lot of work for hire in my writing life, which means people engage me to write things whose shape we roughly agree on beforehand,” Bissell told me. “But my short stories are entirely self-generated and -motivated. Whenever anything good happens because of one of my stories, it feels like something akin to a miracle—makes me feel like I’m an actual writer, rather than a work-for-hire carpenter, no matter how diligent and artful a carpenter I try to be.” Our conversation via email took place in the California time zone, during a brief pandemic lull the week the Omicron variant was announced.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have the last two tumultuous and uncertain years been for you? Where have you been living? Writing?

Tom Bissell: The last two years have been fairly challenging, professionally speaking, but they’ve also been personally rewarding, in that, for 18 months straight, I got to spend 24 hours a day with my daughter and partner. That was and is wonderful—for me and the lady, anyway. Can’t speak for the kiddo. (I suspect she’s tired of us but is too polite to say so.)

Whenever anything good happens because of one of my stories, it feels like something akin to a miracle—makes me feel like I’m an actual writer.

We live in Los Angeles, which has had its Covid peaks and valleys, to say the least. Right now, things here seem to be stuck in a virological stalemate. Not precisely great but not quite terrible either, with no notable signs of improvement. With regard to pandemic writing, I’ve cranked out a fair number of pages, but not nearly as much as I’d once hoped I would. It’s a bit easier to write now that everything has settled into a version of reality that feels roughly like it did before, only shittier.

P.S. A day or two after I sent off these answers to you, me and my entire family came down with Covid. I’m on Day 7 now, and getting a little better, but holy shit Days 3 through 6 were hard. Hit me worse than my partner or daughter. The kiddo has sniffles for two days. I, meanwhile, felt like a building had been dropped on me.

JC: You’ve written short stories from the beginning. Does the short story form still work for you? Why? How has your sense of the form evolved?

TB: The short story form is the only type of prose fiction writing that does work for me, it turns out. I wrote several (unpublishable) novels in my 20s, and I’ve started multiple novels since then, but the sad day came on all my novel projects where I just sort of lost interest in the world I was making up. I don’t have the novelist’s long, steady stride. Fiction wise, I’m more of a sprinter, and just about every short story I start I manage to finish. I used to grieve that I couldn’t finish a novel, but the only novels that should be written are the novels that must be written—and I’ve never had a such a novel inside me. Which is okay. If I can’t finish my novels, why would anyone want to read them?

Stories, for me, are very pure things. I don’t write them to get paid or published—though both outcomes are certainly hoped for!—but rather because some situation or character or scene or voice gets lodged in my head, and the only way to pry it free is to start writing. I’ve been agitated by certain story ideas literally for years.

My view of the story’s form hasn’t changed much in the last 20 years. I was and remain in awe of how various and capacious the so-called short story can be. I like how few “rules” there are when it comes to writing them. Stories might be the least professionalized form of writing left. A good short story can accommodate just about any type of voice or experience or experiment. Probably my favorite contemporary short story is Edward P. Jones’s “Old Boys, Old Girls.” It breaks virtually every rule they teach you in writing school—and in such a low-key, unflashy way. It’s a masterpiece. I like to reread “Old Boys, Old Girls” to remind myself how much life there is in the ancient, hidebound thing we call the short story.

JC: How have 21st century advances in video games influenced these stories? How are video games continuing to change the ways in which stories are written? And ingested by readers? And how do addictions like video games (and cocaine, as in “Love Story with Cocaine,” one of stories in this collection) influence today’s cultural offerings, in terms of content as well as form?

TB: Video games weren’t much of an influence on these stories. Neither were drugs, which I’ve been happily free of for many years now. Effective screenwriting and effective video-game writing and effective prose writing have a few things in common, but these things are all basic and foundational—the way one quadruped resembles another. In fact, I can’t say my game work has had any impact on my literary prose, other than possibly having made it significantly worse. All that said, the culture of video games definitely creeps into these stories, because I’m part of that culture and very interested and invested in that culture.

I go back and forth on how games are affecting our wider understanding of stories. I once believed—and publicly proclaimed—that games were going to cause a seismic shift in how we understood the methods and purpose of storytelling and realign the relationship between story and storyteller. I still sort of believe that, but I’m less excited about it these days. Every new advancement or technology begins in hopeful revolution and ends up as just another way to make money.

That said, there have been a lot of “literary” games in recent years; I’ve worked on a few myself. I’d urge you or anyone to check out Disco Elysium, which is genuinely brilliant, funny, and literarily compelling. At the same time, I often find playing “literary” games, even Disco, to be a bit of a chore. If I really want to approximate the experience of reading a great book, shouldn’t I just, you know, read a great book? I don’t necessarily want my games to resemble my reading experiences, or vice versa.

JC: “The Fifth Category” is a chilling story that reads like a mash-up of a video game and a war crimes trial. (Or a new installment in Gears of War; Judgment, the fourth installment, which you authored, revolves around a war-crimes tribunal.) John, a law professor involved in writing the DOJ opinions that opened the door to torture by the CIA in 2002, including Guantanamo, wakes on a plane to find everyone else is gone. He is on his way home from an international law conference in Estonia, where he has been treated like a pariah. The ending is terrifying. As is the narrator’s hyper-rational tone. What’s the research behind this story? I can’t get it out of my mind.

TB: I was living in Tallinn, Estonia, and during one of my return trips, I had a nightmare in which I woke up on an empty passenger plane. It haunted me for weeks. One day I thought, That would make a great opening for a horror story. I’d never written a horror story before, but was always interested in doing so, if only because Stephen King’s work was a huge deal for me when I was just getting hooked on reading.

I used to grieve that I couldn’t finish a novel, but the only novels that should be written are the novels that must be written—and I’ve never had a such a novel inside me.

So that vague wish—I should write a horror story–was just sort of sitting there in my head, like a potted plant. Then I wound up watching the Frontline documentary Bush’s War, which led to my reading War by Other Means, John Yoo’s appalling and self-justifying account of his role in the war on terror, which in turn led me to Phillipe Sands’s Torture Team, and so on. I made my way through a tranche of Bush administration torture stuff, growing more and more furious that more people weren’t furious. It wasn’t like this stuff was being kept secret! It was out there, everyone knew, and no one cared. I remember thinking to myself: How does John Yoo sleep at night? How can he possibly justify to himself having let the genie out of the torture bottle? Then I remembered my weird empty plane nightmare, which ultimately gave me the staging ground to explore the questions I wanted answers to.

I wound up doing a lot more research … on Yoo, on how the government functions, on international law. I had a couple hundred pages of notes before I wrote the first word of the story qua story. At one point I contrived a reason to fly to Stockholm from Tallinn, just so I could see the what the flight attendants’ private area looks like in a Finnair passenger jet. Pro tip: Be very, very careful while walking around a commercial airplane and jotting things down in your little black notebook. People have a tendency to get the wrong idea.

I’m very glad to know you thought the ending was effective. It scared me a little, too, writing it. It was one of those moments where you’re less writing something than seeing it. It’s really hard to freak yourself out while writing. But that ending freaked me out.

JC: Your story “My Interview with the Avenger” is framed as an article for Esquire magazine, a form you know well. Have you ever experienced such a follow-up with an interview where the tables are turned? Why do you think the concept of the “superhero” is so important today?

TB: Thankfully, I’ve never had an interview turn overtly hostile on me, though I’ve definitely had to work to win some people over. The most difficult interview I’ve ever done was probably with actor-director Tommy Wiseau, whom I (sort of) profiled in Harper’s in 2009, when I wrote an essay about the phenomenon of The Room. (That later, of course, led to me writing The Disaster Artist with Tommy’s costar, Greg Sestero.) Tommy was saying the most bananas, unhinged stuff imaginable, and not answering any of my questions, but I wound up just rolling with it. It’s amusing that there was a time in my life when I believed I could talk to Tommy Wiseau without conversational implosion.

And now the “superhero” piece of your question…. When I wrote “My Interview with the Avenger,” it was, oh gosh—2007 or 2008, I think? Long before the onset of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and long before the average civilian had ever heard of the Avengers, much less seen them in filmic action. I never imagined a future in which my made-up superhero’s name would be shared with the most successful movie franchise of all time.

I thought about changing the name of my low-fi superguy for the story’s republication in Creative Types, but that meant changing the name of the story, too. The problem was I couldn’t think of another superhero name that didn’t sound stupid. But then all superhero names, without question, are stupid. Say Batman to yourself five times. Say Spider-Man. Say Superman or Wonder Woman. The reason we don’t burst out laughing is we’re numb to their ridiculousness.

I was a comic-book kid, so superheroes always meant a lot me, growing up. The characters I spent hours drawing and thinking about as a ten-year-old have now conquered the world. Not sure how I feel about that, to be honest. I’m not a Scorsese-level scold when it comes to superhero movies or anything. I like plenty of superhero movies, and even love a couple of them. But I do find it—let me phrase this delicately—concerning, I’d say, that so many adults find these stories so emotionally compelling. But we live in unheroic times. It could be we need such stories right now.

What I tried to do in “My Interview with the Avenger” was think through the actual nuts-and-bolts ramifications of what being a working superhero would be like. And of course my superhero is kind of nuts—and not in a particularly sympathetic way. Spider-Man’s Uncle Ben famously tells him, “With great power comes great responsibility.” I think it’s likelier that with great power comes great derangement.

JC: The opening lines of “The Hack” nail the set-up: “It would remain a subject of vigorous debate: How exactly did a hack joke wind up in James’s SNL monologue when Sony had sent specific word not make any hack jokes?” Daniel, the narrator, is assistant to James (inspired by James Franco?) in an intimate star/gofer relationship that puts him in charge of everything, including making sure the bread in James’s tuna sandwich doesn’t grow soggy. Daniel understands that Real Hollywood is “pure game theory…a game played alone, behind your eyes, second by thrilling second. It was chess and juggling and Dungeons & Dragons all at the same time…” How much of your own observation of today’s Hollywood is distilled into this story?

TB: Not as much as you might think! I’ve actually been pretty lucky in my Hollywood associations, in that I have yet to interact in an extended manner with a stereotypically monstrous slime-ball. Ninety-five percent of the agents, managers, producers, directors, actors, and crew people I’ve met or worked with have been almost disappointingly normal. I know the slime-balls are out there, though, so I remain on watch.

My goal in “The Hack” was twofold: To write a fly-on-the-wall, insider-Hollywood story that employs the assistant character, Daniel, as the audience surrogate. We’ve seen these stories before, right, so we know what to expect: our audience surrogate will inevitably discover that the inner world of Hollywood is a cesspool of ego and abuse. But I wanted to invert that. The deeper you read into “The Hack,” the more you see that the celebrity characters are all more or less sane, whereas Daniel, the audience surrogate, is a sociopath. I suspect the story grew out of my suspicion that Hollywood corrupts only those who secretly long to be corrupted.

My other goal was to capture the moment before everything in our culture and politics changed. The Sony hack was the bellwether event for so much of the awfulness to come. People thought it was hilarious that this company’s dirty laundry was being aired—but it wasn’t hilarious at all. It was, instead, Pearl Harbor for a new kind of warfare, and rather than react with alarm and concern, as we all should have, we kind of collectively sniggered and rubbernecked. I sometimes wonder if we’re not karmically paying for that misjudgment now.

JC: The title story gives us another glimpse of Hollywood. Reuben, a writer, and his wife Bren, executive producer on a reality TV series, hire Haley, an escort, for a threesome to jump-start their sex life, which has waned since their son was born the year before. Your take on this situation makes it more about class and aspiration than sex (“…virtually everything Reuben said to servers and valets was later subjected to Bren’s undergrad-Marxism rhetorical analysis”).What was the biggest challenge in the story? Making all three characters equally flawed human beings? Turning the tables?

TB: My first run at the actual threesome part of “Creative Types” devolved into something fairly predictable. It became a story about jealousy and hurt feelings, which wasn’t satisfying at all. When I was rewriting the story, I asked myself: What would be a hard, weird thing to go for in a story with so much overt sexual content? Pretty quickly I had my answer: A threesome story that’s actually about the ineradicable love we feel for our children. So I gave myself the challenge of trying to write a story that’s totally filthy but also . . . kind of warm-hearted and sweet? Even good-natured? It’s not my place to claim that I succeeded, but I will confess to dearly loving the story’s escort character. I didn’t want her to become the prototypical hooker with a heart of gold, but I did want her to be the story’s most admirable, clear-sighted character. I guess rather than equally flawed, I wanted them all to be equally lovable. Then again, people sometimes complain that my characters are unlikable. But when I read or write fiction, the last thing I’m thinking about is whether the characters are likable. Literature isn’t a dating site.

JC: Two of the stories from your first collection, God Lives in St. Peterburg, were made into films as was your 2013 book with Greg Sestero, The Disaster Artist. Any TV/film projects in the works for these stories? Which would you like to see transformed?

TB: I’m still sort of attached to The Mosquito Coast, which I co-developed with Neil Cross. In late 2019, I shot a pilot that adapted David Kushner’s nonfiction book Masters of Doom for NBC/Universal, a project that unfortunately died of Covid-19. I’m currently working on an adaptation of a J. G. Ballard novel for a studio and worked for a while on an adaptation of a T. C. Boyle novel that for various reasons I can’t name. I do a lot of adaptation work, which I really enjoy. There’s something deeply satisfying about ripping apart someone else’s book and reimagining it. Which is probably why I’d never, ever want to adapt my own stuff. Dentists don’t give themselves root canals!

I don’t want any formal role when my own stuff gets adapted: If it’s bad, it doesn’t matter, because I had nothing to do with it. But if it’s good, I can still take all the credit.

There’s another reason I don’t want any formal role when my own stuff gets adapted: If it’s bad, it doesn’t matter, because I had nothing to do with it. But if it’s good, I can still take all the credit.

JC: Six of these seven stories previously appeared in small press publications—Agni through Zyzzyva–and were selected for Best American Short Stories, Best American Mystery Stories, and The Pushcart Prize Anthology XLII (2018). What is the value of small literary publications and “best of” anthologies to literary culture in these times?

TB: One of the great mysteries of my career, from my point of view anyway, is why I can’t seem to publish my stories in big glossy magazines, despite writing nonfiction for big glossy magazines pretty consistently. God knows I’ve tried. Little magazines are where my fiction lives, and I’m intensely grateful to every single one that’s ever published me. I donate money to small press publications, I subscribe to them, I read them. I wouldn’t claim that the stories in small press publications are consistently better than, say, the stories that appear in The New Yorker, but I do think the fiction that appears in small press publications tends to be … I dunno … more variegated, maybe? There are a million exceptions to that, God knows—“Old Boys, Old Girls” first appeared in The New Yorker—but by and large I think it’s true. American literature would be impoverished without small press publications.

I’ve been a full-time professional writer for 20 years now. I’ve been immensely lucky in my career and have had a lot of good stuff happen to me. But I’m still thrilled to my atomic core whenever one of my stories (or essays) gets selected (or even honorable mentioned) for Best American. I read Best American Short Stories, BA Essays, and BA Travel Writing cover to cover virtually every year and have done so since I was a senior in high school. I’ve discovered so many great writers through Best American. The day I’m asked to be a Best American guest editor is the day I can die content. Which is probably why I’m doomed to die a wan and disappointed wraith.

JC: What are you working on now? Will you continue to write short stories? Why?

TB: Other than the aforementioned J. G. Ballard thing, I’ve got a couple television projects in the offing. Whether or not they actually happen is beyond my ability to predict. Screenwriting amounts to a strange kind of writing life: Getting paid for things that don’t happen. I’m also working on what I suspect will be the last video game I’ll ever write, the main character of which is, among other things, a beloved and globally recognized literary character. I wish I could say more but cannot. Finally, I’m writing a nonfiction book about the history, theory, and practice of literary adaptation. One of the chapters from my adaptation book was recently published in Lolita in the Afterlife, a wonderful essay collection Jenny Minton edited about Nabokov’s infamous and indelible novel.

As for more short stories, I recently finished a new one that will appear in the spring issue of Zyzzyva, and I’m hoping I can convince my publisher to allow me to insert it into the paperback edition of Creative Types. I expect to write stories till the day I die. So when the dire hour comes and I learn I’m not much longer for this earth, I know what I’m going to do, which is immediately start writing a short story, if for no other reason than being reasonably certain I’ll actually finish it. Brevity is literature’s most underrated virtue—and life’s most overrated virtue.

__________________________________

Creative Types by Tom Bissell is available now from Pantheon.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.