To Write a Revolution on the Sky: On the Radical Legacy of Curtis Mayfield

Ayana Contreras Considers How the Soul Legend’s Sound Is Still Relevant Today

Years ago, I found a lovely promotional 45 rpm record—Curtis Mayfield’s “We Got to Have Peace.” Grooves ghostly white. The single is taken from Mayfield’s Roots album, released in 1971. Roots was released months before the Superfly soundtrack, and it is just as wonderful. Released on Chicago’s Curtom Records, the rare promotional record was crafted of creamy white wax. Colored vinyl from this period, 45s in particular, is quite rare. Colored vinyl records were generally created to make people (DJs in particular) stop and take notice; even some 40 years later, notice I did.

In the year following the epic 1970 album Curtis, Mayfield mounted a campaign to fully express himself as a solo artist in ways he could not as a member of the soul group the Impressions. As early as the mid-60s, some of the Impressions’ most beloved songs (including “Keep on Pushing” [1964] and “People Get Ready” [1965]) were implicitly political, intended to inspire listeners. “I had the love thing very strong,” Mayfield recalled in 1975:

We had songs like “Keep on Pushing,” and “Amen.” Even “It’s All Right” was a song of inspiration to me. You know:

When you wake up early in the morning

Feeling sad like many of us do

Hum a little Soul

Make life your goal

And surely something’s got to come to you.

Mayfield further reflected:

I think a lot of that came from my grandmother [a minister at the Traveling Soul Spiritualist Church], and I guess even as I slept through many sermons they kind of piled up in my head. That was where “Keep on Pushing” and “Choice of Colors” came from. Every once in a while, I felt it was important to say something more than just “shake your shaggy shaggy” or “do wow,” you know?

According to poet and soul singer avery r. young, the ministry inherent in Mayfield’s music was no accident. To the contrary, Chicago soul music hash gospel music DNA coded deep within its bone marrow. young argues that Black Chicago’s topology produces a unique mix of gospel and soul, the sacred and the profane:

Chicago Soul music is… merging of two gifts that Chicago has given the world: the Blues and the Gospel. And what happens in most spaces, particularly the South, you have the church that’s by itself and then you have the juke joint… usually in separate spaces in a town or a city. But, in Chicago on a given street, the tavern and the church house are next-door neighbors.

And what happens, when anybody passes there, right at the gangway [or alley], there’s usually a bleed of what’s coming from the church house and what’s coming from the tavern. And that is the crux of soul music.

There’s one thing where the preacher is saving souls, and I believe Pops Staples and Mavis [Staples] was specifically about saving humanity. Encouraging folks to be humane to each other. Which is a very different ministry. Not watered down, but a very different ministry.

Curtis Mayfield, what he wanted to do with that bleed, he wanted to make it real pretty. I don’t think Baba Curtis ever wrote on a sheet of paper. He wrote on the sky.

Mayfield frequently worked heavenly themes into his music. In “People Get Ready,” Mayfield announced that all manner of freedom was near, riding the metaphorical train commonly found in Black spirituals such as “The Gospel Train.” He understood that “the Train is somewhat of a symbol of God Himself coming to take on and bring all the people who have somewhat gotten themselves together and may possibly be able to venture over to the other side of the world… or heaven.”

But, despite the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the same social struggles (such as poverty, injustice, and blight) were omnipresent in the Black community through the end of the decade. Mayfield wanted to share messages of uplift that were more insistent and urgent, and he needed more than a metaphor to get his messages across. One of his first political records was “We’re a Winner,” recorded at RCA’s Chicago studios in 1967 (studios Mayfield later bought). The session included a lively audience that added encouraging whoops and hollers to the recording. Before the song fully lifts off, a woman distinctly calls out “sock it to me, baby!” in the lull between horn stabs. These lines—

I don’t mind leaving here

to show the world we have no fear

Cause we’re a winner

and everybody knows the truth

We’ll just keep on pushin’

Like your leaders tell you to.

—allude to a more pointed, assertive stance. Yet the lyrics still maintained some sense of conservatism, suggesting that listeners acquiesce to leaders. Mayfield had long been interested in the business side of recording, stating in 1975 that he had “always respected [Black-owned Chicago record label] Vee Jay and all the independent companies… especially Motown and their ability to do great things in the business.”

In 1968, after years of recording for ABC-Paramount and writing and producing for other artists on a variety of labels (Okeh and Constellation among them), Mayfield put his money where his mouth was and opened his own label at 8141 South Stony Island Avenue in partnership with his then-manager, Eddie Thomas. Curtom Records was in fact his fourth foray into independent labels; Mayfield Records, Thomas Records, and Windy C Records all came before, but his Curtom label had much higher stakes.

While his earlier labels produced other performers (most successful of which being the Five Stairsteps), the lion’s share of Curtom’s production centered on his compositions. It would then become the home of his group, the Impressions. Armed with a freshly inked distribution deal from Neil Bogart at Buddah Records, he was gambling with the Impressions’ ten-year track record of success, leaving ABC-Paramount (a major label) to chart his own path to industry success.

“This Is My Country” (1968) was one of Curtom Records’ first releases. The song’s political message was even more pointed than “We’re a Winner,” with lines like these:

I’ve paid 300 years or more

Of slave driving, sweat, and welts on my back

This is my country

Too many have died in protecting my pride

For me to go second class

We’ve survived a hard blow and I want you to know

That you must face us at last.

The phrase “This is my country” is still loaded for a multitude of reasons 50 years after the Impressions laid it down on wax. African Americans, a population with a long, multigenerational lineage in the United States, are a unique tribe: we are in many ways alienated from other non-Black Americans (as evidenced in “This Is My Country”). A couple of radio stations banned the song in late 1968; some disc jockeys and radio executives considered the song too radical. In response to that idea, Todd Mayfield (son to Curtis) posed to me the following question: “What is radical? One person’s radical is another person’s revolutionary. It just depends on what side of the line you’re on.”

Mayfield wanted to share messages of uplift that were more insistent and urgent, and he needed more than a metaphor to get his messages across.

In April 2018, 50 years after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on that balcony at the Lorraine Motel, and nearly 50 years after the release of “This Is My Country,” I discussed the idea of “just Blackness” with Naomi Beckwith. At the time, Naomi was Manilow Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. She curated 2015’s The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now, a multimedia exhibition built around the legacy of Chicago’s AACM, and in 2018 she co-curated a gorgeous survey of the work of Howardena Pindell, among other brilliant shows. She is also a Black Chicagoan, raised in Hyde Park.

AYANA CONTRERAS: We were talking about this idea of “just Black” not being valued in the same way [as Black people with backgrounds directly connected to countries outside the United States].

NAOMI BECKWITH: Well, exactly. You know, I’ve been in communities where people always ask about international origin. Where you came from.

AC: They want you to be Jamaican, or something?

NB: Jamaican, Dominican, Haitian. Trinidadian is a big one [laughs]. And, you know, all that’s wonderful and fine. One should really find some pride in one’s national origins. Chicago is not an immigrant community in that way.

Not to say that it doesn’t have people of Black descent or African descent who are immigrants, but its sense of belongingness is about belonging to this community in the US. We are not ex-pats. We are not from elsewhere. We are not trying to make distinctions between ourselves and other folks who look like us and even those who do not. [We are] trying to be together.

People often would ask when I was in New York, “Where are you from?” And I would say “Chicago.” And then they would ask, “But, where are your parents from?” And I would say, “Chicago.” And then, they would say, “Bu-Bu-But, your grandparents?!”

There was a sense that one could not be a Black person in the US and… have a long heritage in this country. And my upbringing in Chicago taught me this place is mine, and that I have to claim that.

Because that question of “Where are you from?” isn’t just about “What kind of special Black are you? What do you want to brag about that isn’t about being a basic American Negro?,” which has its own class implications. But it is also about not feeling like you belong here. And some people take that as a romantic notion, but to me that’s not cute. You really need to be effective where you are.

Back in the 1960s, the message of “This Is My Country” resonated with its target audiences and it was a hit on Black radio. However, Fred Cash and Sam Gooden (the other members of the Impressions) were becoming more and more uncomfortable with Mayfield’s increasingly edgy material. Though he continued to write and produce material for the Impressions, Mayfield began his solo career in 1970, which allowed him to voice his most personal and dogmatic ideas without having to deal with group politics; his first solo single was “(Don’t Worry) If There’s Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go.”

An apocalyptic Afro-Latin-tinged funk romp, the recording was his boldest message to date. In his initial solo outings, Mayfield’s songs were markedly longer, the basslines were funkier, African percussion became prominent, and the horns were a bit jauntier. Albums were bound together with loose themes. Though he had acquired great mastery of the three-minute radio-ready single track, Mayfield enjoyed using the album format to more fully express his artistic vision. Commenting on record industry conventions in the 60s, he noted in 1975 that “usually you put all your B sides on an album, along with the single records you had put out.

Very few people ever thought of recording an album as a complete concept, a story to tell from the first cut to the last to a point that even if you just read the titles of the songs they would just about make up their own paragraph.” Mayfield exhibited an unwavering commitment to exploring the full spectrum of Black experiences through his songs and their political messaging. Mayfield was particularly keen to express the voices of urban Black men: those who struggled, scratched, loved, dreamed, and believed.

Despite this focus, he wrote nuanced compositions from women’s perspectives, as well (for instance, cuts from the soundtracks to Claudine [1974] and Sparkle [1976]). His political soul sound is still relevant today, wrought with an eloquent and earthy simplicity. “Move on Up” is a Black cultural anthem. “We Got to Have Peace,” the soul composition etched into my ghost-white vinyl record, presents a bassline so much larger than life it might be misclassified as menacing save for the jubilant message holding the center:

And the people in our neighborhood

They would if they only could

Meet and shake the other’s hand

Work together for the good of the land

What happens, though, when a cultural artifact is no longer revered? Initially, I counted it a privilege to hold that ghost-white vinyl. To bear witness to an artifact; a moment in time, captured and etched. One day years later I proudly showed my creamy-white 45 rpm record to Todd Mayfield. He quipped that, as children, he and his siblings used to use copies of the record (not a chart-topping success by any means), as Frisbees.

__________________________________

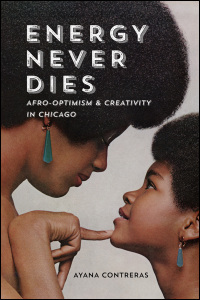

From Energy Never Dies: Afro-Optimism and Creativity in Chicago by Ayana Contreras. Copyright 2021 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

Ayana Contreras

Ayana Contreras is a radio host/producer at Chicago Public Media, a founder/blogger at darkjive.com, and a columnist and reviewer at DownBeat Magazine.