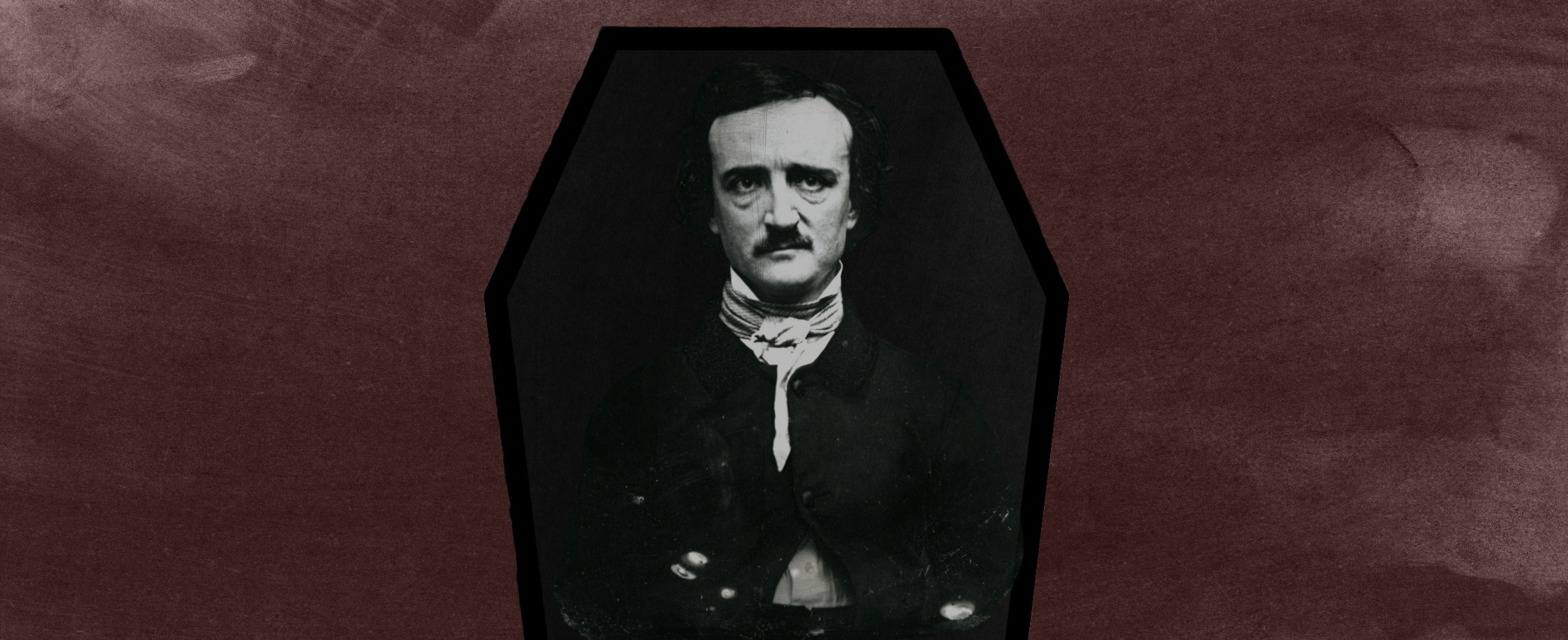

To Haunt and Be Haunted: On the Exhumation of Edgar Allan Poe

Ed Simon Explores the Terror of Being Buried Alive and Americanism in Poe’s Work

Imagine that you’ve been buried alive.

Don’t question the specifics, whether you’ve been kidnapped or unfortunate enough to fall victim to poorly trained pathologists and morticians, for either way you’ve been entombed in the cold earth while still breathing. Just imagine it—you’d abruptly awaken in the darkness, a blackness that’s so all-consuming that your eyes could never adjust beneath the earth’s chill frost line.

Deprived of the sense of sight, but able to hear the shifting of ground on the other side of the coffin’s thin wood, you’d of course panic, but you wouldn’t be able to sit up, or even necessarily raise your arms. You’d fruitlessly knock and scratch at the hard maple less than a foot, maybe only a few inches, from your face. The six feet of dirt separating you from the fresh air of freedom could weigh as much as fifteen thousand pounds so that even if you tried to break through it would be futile.

At best you’d breach the lid, and all of that dirt would cave in and suffocate you quickly, which might be merciful. A person could survive between five and six hours after being buried alive, though panicked scrambling and hyperventilating would deplete the available oxygen quickly.

Eventually, assuming that you didn’t have a heart attack, you’d be suffocated by the increasing carbon dioxide. All of that dirt wouldn’t entirely dampen the sound of your screaming, so there’s always the chance some benevolent gravedigger could save you. Unless he’s the one who buried you to begin with.

There was, as with many of those living in the gloaming aesthetic twilight of Romanticism, a tendency to confuse the characters with their creator, a narrator with the author.

“There are certain themes of which the interest is all-absorbing, but which are entirely too horrible for the purposes of legitimate fiction,” wrote Edgar Allan Poe in his 1844 short story “The Premature Burial,” first printed in The Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper. Poe himself wasn’t buried alive. A common misconception, of the sort that was spread about the cadaverous-appearing Southerner by Rufus Wilmot Griswold, rival writer and self-appointed literary executor, who fervently maligned Poe in his obituary.

“Edgar Allan Poe is dead” wrote Griswold in an 1849 edition of the New-York Daily Tribune, “but few will be grieved by it.” The author of “The Raven” and “The Bells,” of “The Masque of Red Death” and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” portrayed as an incurable dipsomaniac married to a child who also happened to be his cousin, a fevered laudanum addict, an itinerate madman wandering the streets of Baltimore.

There was, as with many of those living in the gloaming aesthetic twilight of Romanticism, a tendency to confuse the characters with their creator, a narrator with the author. Griswold writes that Poe’s work illustrated a “morbid sensitiveness of feeling, a shadowy and gloomy imagination, and a taste almost faultless in the apprehension of that sort of beauty most agreeable to his temper.” Suddenly Poe was no longer a professional writer, but he was Roderick Usher, or the doppelganger-murderer William Wilson, or the anonymous sociopath haunted by the beating of his victim’s heart. With such easy elisions between author and work, it’s no wonder that many assumed he suffered the same fate as “The Premature Burial,” but Poe’s corpse is not his corpus.

There have always been inconsistencies around the circumstances of Poe’s death, however. Hypotheses have been proffered from the moment that Poe turned up in Ryan’s Tavern on October 3rd, 1849 in that morose city of dark rowhouses, his family’s native Baltimore. Disheveled and delirious, while dressed in a stranger’s clothes, Poe was committed to the Washington Medical College where he died five days later. The attending physician, whose story had a tendency to change, provided little in the way of material evidence as to what caused Poe’s death and why he showed up “rather the worse for wear… [and] in great distress” in the rare bar where nobody knew him.

More than 175 years later the answer to what killed Poe—or who?—remains unsolved. Syphilis, meningitis, or epilepsy; cholera, apoplexy, maybe poisoning; hypoglycemia, diabetes, heart disease—even rabies, have all been proposed.

Just as fascinating are Poe’s burial and his reburial 26 years later, an exhumation that adds to his mystique, even if the raw particulars of that reburial do nothing to justify the urban legend of his living entombment. Appropriate to the popular conception of the morose genius, Poe’s initial 1849 funeral, held amidst the October gloom, was sparsely attended. His coffin was simple and his grave unmarked. The presiding minister elected not to deliver a funeral sermon; dirt was shoveled on top of the mahogany box only three minutes after the service began. An impressive marble monument paid for by a relation had been destroyed when a train derailment near the masonry yard pulverized the marker, so Poe received a number on a sandstone grave. The few mourners walked away beneath the crooked, treeless oaks and hickories of the Westminster Presbyterian burying ground.

By 1875, Poe’s critical fortunes had improved. With much ceremony, he was to be exhumed and reinterred at a more prominent location in the same graveyard, a large, marble monument finally marking Poe’s final repose. When the gravediggers hoisted the decayed coffin aloft, they didn’t find a cracked lid with boney fingers jutting out or any panicked scratches on the underside of the coffin, but they did drop the box, which splintered apart (some relic-stealing lollygaggers filched moldy, rotted fragments of the wood), the poor condition of the coffin possibly contributing to the dark rumor about the author’s supposed premature burial.

For as much as Poe is often reduced to the macabre, he was a stunningly diverse author, arguably an early creator of science fiction, and most certainly the inventor of the detective story.

While the cemetery sexton discovered that Poe’s skeleton, still wearing those preserved mourning clothes and with a few greasy locks of black hair clinging to his pate, was in relatively good condition, there was a strange sound coming from inside his skull. As they shifted the corpse from the ground, some small and hard artifact clanged about as if a rattle. It’s been hypothesized that it might have been a calcified tumor left behind as the rest of the soft, grey tissue of his brain decomposed, the last remnant of his thinking reduced to this stony nugget that very well may have been responsible for the erratic nature of his final days. Perhaps some accidental truth in the contemporary obituary from the Richmond Semi-Weekly which claimed that Poe perished from “congestion of the brain.”

Adequately hoisted from the earth then, on an autumn morning 150 years ago today Poe was reinterred into the Maryland ground, now marked by a memorial decorated with a bronze frieze depicting the author. An unsigned article in The New York Herald celebrated this “Tardy Justice to the Memory of One of America’s Greatest Poets.” A ceremony was held a month later; civic leaders and family attended, while many prominent poets were invited but only Walt Whitman showed up (Alfred Lord Tennyson sent a dedicatory verse).

Regardless, Poe’s physical slumber has remained undisturbed for the past century-and-a-half even while he remains a disquieting figure in American culture, perhaps still our most popular canonical writer, though his vision is at odds with that strain of national utopianism which is maybe our most cursed affliction.

For as much as Poe is often reduced to the macabre, he was a stunningly diverse author, arguably an early creator of science fiction, and most certainly the inventor of the detective story. Even his gothic tales explore the grimmest of themes in all their multiplicity, whether in the beat of a disembodied heart pulled from the ribcage of a mutilated corpse or the haunting specter of death cursing aristocrats gathered in the penitential sepulcher of their castle. Which is why it’s even more notable that the cold suffocations of the ground are such an idee fix for Poe.

Five years before publishing “The Premature Burial” Poe describes the accidental entombment of the cataleptic Madeline Usher with her skin’s “faint blush” and “suspiciously lingering smile;” in 1846’s “The Cask of Amontillado” presents an intentional interring as Fortunato is imprisoned by his supposed friend behind a wall of bricks. “Berenice,” published in an 1835 edition of the Southern Literary Messenger, is the earliest exploration of Poe’s macabre fixation, and arguably the most disturbing, wherein an entranced protagonist pries his wife’s teeth (with which he had an unnatural obsession) from her head after she was accidentally buried following a seizure.

Realizing what’s happened, the character drops a bedside ebony box that shatters on the floor revealing “some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with many white and glistening substances that were scattered… about the floor.” But it’s with a fascinating intermingling of fact and fiction where Poe most fully explores this theme in “The Premature Burial,” a chimera of essay and story that in addition to a first-person account of its very subject also presents past tales of those who awaken in terror six-feet-under.

“That it has frequently, very frequently, so fallen will scarcely be denied by those who think,” writes Poe, and though premature burial might not exactly have been common, it’s also unheard of. In an era absent contemporary standards of funerary practice, there were substantiated accounts of those who were buried while still alive. A decade after Poe’s reburial, there was a gentleman named Jenkins from Buncombe County, North Carolina of whom an unsigned 1885 account from The New York Times described what the bereaved family discovered when his corpse was to be transferred to an ancestral plot. “[T]o the great astonishment and horror of his relatives the body was lying face downward, the hair had been pulled from the head in great quantities, and there were scratches of the finger nails on the inside of the lid.”

Fundamentally, taphephobia concerns the stubborn endurance of that which we thought we’d buried. They’re ghost stories about being haunted and being the haunting.

In 1886, another unsigned missive (what journalist worked that beat?) describes how the exhumation of an Ontario woman revealed that “Her shroud was torn into shreds, her knees were drawn up to her chin, one of her arms was twisted under her head, and her features bore evidence of dreadful torture.” There are many other examples, mostly from the nineteenth and occasionally the early twentieth-centuries, but some from years that distressingly begin with a “20.”

Taphephobia—the fear of being buried alive. The reality of that terrible predicament was common enough that multiple solutions were proposed, from grave-side alert bells deployed from within the coffin to catacomb escape hatches, but despite the lurid examples given by Poe (and myself) it’s a vanishingly unlikely fate, most of us already a bit ripe before we’re given over to vermiculation. Despite that, Poe’s contemporary authors shared his reservations about mortuary mishap. Hans Christian Anderson slept with a card embossed with the helpful statement “I only appear to be dead;” Wilkie Collins did the same. Nikolai Gogol’s will specified that his corpse must show visible signs of putrefaction before burial.

For these authors perhaps there was the fear of losing control of one’s work, of the author’s metaphorical entombment (after all, Griswold was the final gravedigger for Poe, and on the former’s terms). No wonder it was that great reader of Poe the French philosopher Roland Barthes who in 1967 could describe in corpuscular terms the way in which a literary work is nothing more than a “tissue of quotations,” and how readers need to have “buried the author.”

Or, perhaps, there is the uneasiness surrounding fiction itself, how inert marks can so fully imitate life, like the blush on a body’s cheek, until there is uncertainty around what is real and what is fake, what is alive and what is dead. “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague,” writes Poe, “Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?” A fair appraisal of the writer’s uncanny art.

Fundamentally, taphephobia concerns the stubborn endurance of that which we thought we’d buried. They’re ghost stories about being haunted and being the haunting. The author was variously a citizen of gothic New York and red-bricked Philadelphia, the novice poet who signed his debut collection after his place of then-residence simply as “By a Bostonian,” and he has since become identified with Baltimore, though of course he was foremost a Southerner.

Yet despite being our first great national writer, there is little of America in Poe. His work is often set in some fantastical Old World locale, a fantasy of manor homes on the moors filled with antiques and rare books, an Anglophile and Francophile’s fantasy of Europe. No New York or Philadelphia, no Baltimore or Richmond in Poe’s writing. How could there be? Poe despised didacticism, he spurned the Transcendentalist and abolitionist pens from Emerson’s to Longfellow’s that wrote against our national shame, but there is no true American book if it doesn’t address genuine monsters.

Here is the paradox, for in his silence Poe was actually the most American, exemplifying our national talent at sublimation and repression. Edgar Allan Poe, adopted son of a Virginian enslaver; Edgar Allan Poe, who managed the sale of a human being owned by his mother-in-law. “No early American writer,” notes Toni Morrison in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, “is more important to the concept of American Africanism than Poe.” A writer who, as with the best of them, always said more in what he didn’t say, obsessed with that which was too horrible to contemplate. Such history can be buried, but it’s buried alive. The scratching at the lid is incessant.

Ed Simon

Ed Simon is the Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and the editor of Belt Magazine. His most recent book is Devil's Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, the first comprehensive, popular account of that subject.