I wake to a complete absence of sound in a world biding its time before coming to life. Enclosed by darkness and sky, I lie with my eyes directed like conduits toward the great expanse, but there is nothing there, not even air. In the midst of the vast silence my chest begins to tremble and shake. The waves intensify; something growing inside threatens to force its way out. My ribs are pried apart like the bars of a cage. There is nothing I can do except submit to this formidable force, like a child groveling on the floor at the feet of an enraged father, never knowing when the next blow will strike. I am that child. I am that father.

Before the world is fully formed, I rush out into the dawn with my knapsack on my back and the hand orged ax in my fist. A short distance from the low barn I stop and shelter at the edge of the forest, pretending to busy myself with my clothing in case someone should see me and start to wonder; I wind a shoelace round and round, empty my cap of invisible lice, pretending to shake them onto the swarming anthill at my feet. All the while I watch the farmyard out of the corner of my eye. The first smoke of the morning rises from the cabin stove, signaling that the household is astir.

And then she emerges. Empty pails swing from her hands. Her headscarf stands out, white like a winter ptarmigan; her face is a circle of light, her eyes bright, her brows dark. I imagine the smoothness of her cheeks and her small rosy lips singing softly, shaping tender little words. The cows, their udders taut, low in response and expectation when she opens the heavy barn door and slips inside. It all happens at such speed, far too fast, and I try to keep my senses sharp, to hold this picture so that I can summon it again and again. And yet it is not enough. I have to see her tomorrow as well. Her swinging hips under the apron, the gentle round of her bosom, the hand that grips the latch on the barn door. I steal closer, almost breaking into a run across the farmyard as if I were a thief, and at the door I stop. I let my hand close round the handle. My rough, sinewy hand on the place where hers, so small and soft, has just been. Inside, her fingers squeezing the cow’s large teats, squirting white jets into the pail. For a split second I pull on the handle as if to enter, but I promptly turn and hurry away, afraid someone will have seen me. But I keep it in my hand for the rest of the day. The warmth from her skin.

*

At mealtimes i always wait until last. i hold back in the corner while the pastor’s wife places the heavy cauldron of oatmeal on the table. It is smoking and black as death on the outside, as though fetched straight from the devil’s inferno. But inside, the porridge is light and golden, slightly grainy, creamy where it sticks to the wooden ladle. Brita Kajsa stirs with the broad wooden spatula, digging down to the bottom and then up again, breaking the skin that has formed on top and filling every corner of the cabin with the aroma of hay and pollen. The children and hired hands sit waiting; I see their pale faces, a silent wall of hunger. Her expression stern, she takes the bowls and gives large scoops to the older and smaller dollops to the younger ones; she serves the workers and the visitors who have dropped in. When they all have received their share, heads are lowered and fingers intertwined across the table. The pastor waits until there is quiet, then he too bows his head and gives heartfelt thanks for everyone’s daily bread. They eat in silence, apart from the sound of chewing and the licking of wooden spoons. The older want more, and more is given. The breaking of bread, the eating of cold boiled pike with deft fingers, bones piling up on the table like shiny pins. When everyone has almost finished, the mistress will chance to cast an eye toward the corner where I sit.

I see the master turn as well. His eyes are glazed; I detect the pain in them and how he struggles to conceal it.

“Come and eat too.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“But come and sit down. Make room for Jussi, children.”

“I can wait.”

I see the master turn as well. His eyes are glazed; I detect the pain in them and how he struggles to conceal it. A brief nod from him brings me to the table. I hold out my guksi, the wooden cup I crafted myself up in Karesuando, the one that has accompanied me on my life’s journey. At first it was white as the skin of a suckling babe; over time it has darkened with sun and salt and a thousand washings. I feel the weight when the mistress empties her ladle and I watch her scrape the sides to gather more, but I am already back in my corner, cross egged on the floor. The sticky, barley-tasting porridge I devour has cooled by now to the same temperature as my mouth. I feel it slip down my throat, then enclosed by my stomach’s muscles. There it grows into the strength and warmth that will help keep me alive. I eat like a dog, ravenous and watchful.

“Come and have some more,” the mistress urges.

But she knows I will not come. I eat only once. I take my allotted portion, never more.

I might leave at any moment. As a wanderer does. I am here now, and the next thing you know I am somewhere else. I get to my feet, grab my knapsack, and walk. That is all.

The cup is empty. I wipe my thumb like a swab round the curved surface and pass my tongue over it; I lick and suck until it is all clean. It slides gently into my pocket. The cup is what provides me with food, drawing to it the edible things that happenstance delivers. Many times, weak with hunger, I have been close to collapse. But whenever I took out my cup, it was filled with a fish’s head. Or a reindeer’s blood. Or with frozen berries from a mountain slope. Just like that. And I have eaten and regained my strength. Enough to withstand the day. This is all I hope for and this is how I have survived. This is why I sit down on the floor, for never would I assert myself or make demands, never snatch like a raven or snarl like a wolverine. I would rather turn aside. If no one sees me, I stay in the shadows. But the mistress, she sees me. I ask for nothing, but she provides nonetheless. Her brusque kindness, the same concern for all beings, for cows, for dogs. All living things need to survive. That is about the size of it.

*

I might leave at any moment. As a wanderer does. I am here now, and the next thing you know I am somewhere else. I get to my feet, grab my knapsack, and walk. That is all. When you are poor, you can live like this. Everything I own, I carry with me. Clothes on my back, knife in my belt, fire striker and cup, horn spoon, pouch of salt. Their combined weight is almost nothing. I am agile and fleet of foot, in the next river valley before anyone misses me. There is hardly a trace of me left behind, no more than an animal’s. My feet tread on grass and moss that spring back up. When I build a fire I use old firepits, and the ash I make settles, invisible, on the ash others have made. I answer the call of nature in the forest, lifting up a clod of earth and replacing it afterward. The next traveler can place his foot right on top without noticing a thing; only the fox can detect a faint human scent. In winter my ski tracks fly across the pillowy skies of snow several cubits above the ground; and on spring’s arrival all the pockmarks left by my sticks will melt away. It is possible for humans to live this way, without damaging, without disturbing, without really existing: being like the forest, like a host of summer leaves and autumn detritus, like midwinter snow and myriad buds opened by the sun in spring. When it is finally time to leave, it is as though you have never been here.

__________________________________

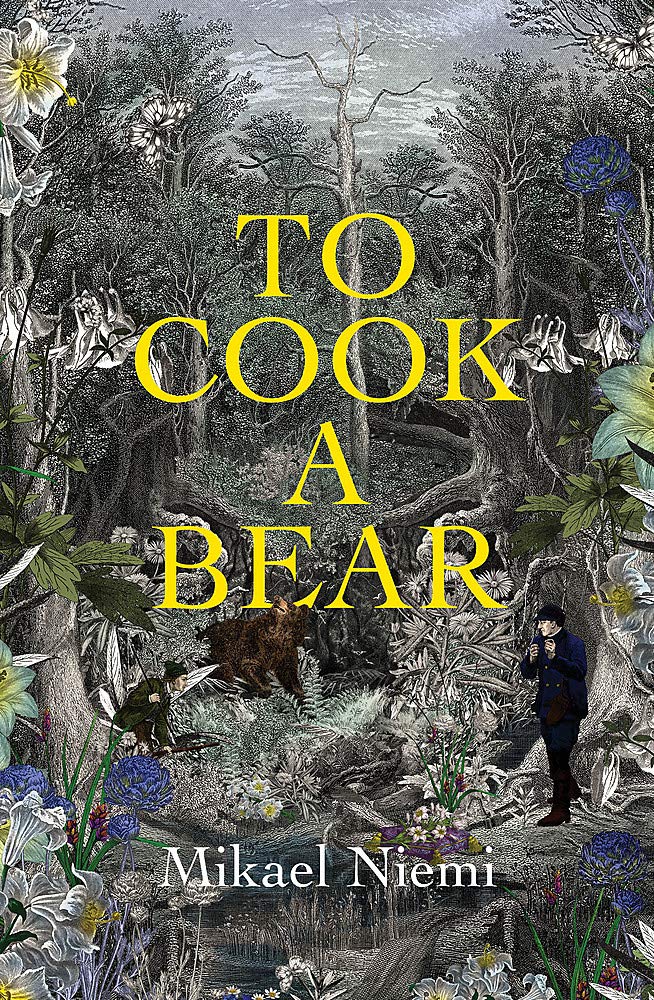

Excerpted from To Cook a Bear by Mikael Niemi (trans. Deborah Bragan-Turner). Excerpted with the permission of Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Mikael Niemi.