The afternoon that Jacob called, the Yitzhak Bloom Senior Curator of Modernist Paintings came down to Rachel’s office in the basement of the Museum of Jewish Art and asked her, as he sometimes did, if she wanted to go to lunch.

Rachel worked alone, in a room with a desk and a phone. It was a setup out of East Berlin, the interrogation chamber from every spy movie: bare floor, neon light tubes affixed to the ceiling, a metal desk in which all the drawers were locked, and two chairs, one she sat in and one she faced, though that one was always empty, and she was never sure whether she should feel like the prisoner or the interrogator. Beyond this, she had only a map of the galleries and a chart providing each painting on display with a numeric code. At first there had been a Monet print on the wall, as well as a framed Ansel Adams photograph leaning in the corner, so that the room felt less like an interrogation chamber than a high school guidance counselor’s office, but they both disappeared during her first week, and the room reaccrued its essential character. Several times she had moved the empty chair into the closet down the hall where the coffee machine was kept —if everything else could vanish, so could a chair—but it was always returned by the next day, sitting across from her, bare, somehow recriminatory, vaguely expectant.

So having another person in her space was always a little surprising, even if the curator, gazing at her with his usual mix of mild reproach and gauzy concern, seemed not abundantly different from the empty chair. Also, he would not cross into the room. He hesitated on the threshold as he asked her to lunch, brisk, polite, a little genteel and a little sweaty, dressed totally in seersucker.

For lunch they got sushi. “Who could eat anything hot in this weather?” the curator said, every time, no matter the season. Perhaps she was supposed to derive something meaningful from this. She did not like sushi that much, but enjoyed how long it took the curator to eat it. He was a precise man and he separated the chopsticks with a single clean snap, rubbed them together, locked them between his fingers and never once put them down or had to readjust them during the meal. He was dexterous and blond, fortyish, his face changed colors as he spoke, went from sallow to florid, his name was Simon, and because he had to avoid getting soy sauce on his seersucker suit, he took forever to eat.

He liked to ask her questions about her aspirations. “Would you want to work back upstairs?” “Did you ever intend to go into academia?” “Have you considered digital platforms?” Between questions he dipped his fish in soy sauce, raised it vertically, and then at the very last moment, in ridiculous slow motion, leaned in with his mouth already open like an ancient tortoise and closed his teeth around it. He didn’t much listen to her answers, but in her experience with curators, it was rare enough that he even asked the questions. After Trump’s election he had started coming by more often, ostensibly to check that she was doing all right, that this had not been the final blow. “You know,” he said. “The straw. The camel. After the year you’ve had.”

He’d hired her originally—she supposed—because they hit it off talking about Cubism in her interview, and she’d long ago noticed that his syntax matched his interests. He was a Cubist conversationalist. All fragment and implication. She liked it. The tenuous logic, the straight-on side-eye of a simple sentence. The way he referenced her grief only in euphemisms. She could pretend not to know what he meant.

This time, Rachel ordered miso soup and udon noodles. He looked concerned. “Deviation is the heart of progress,” she said and smiled and slurped soup and wiped her chin and then watched his eyes. Beneath Simon’s precision lurked, she felt sure, a simmering prissiness.

“Are you looking forward to our Lurio exhibit?” he asked.

Rachel had managed to ensnare a noodle with her chopsticks, but it was a very long noodle, and caught between sucking it slowly into her mouth while he watched or biting it, she chose to bite it. The severed half plopped limply back into her bowl. She smiled. Lurio was her specialty. A chapter from her dissertation on his depiction of desire, what she had called “subject-object intimacy,” in his early Paris portraits had been well published. Their standing collection and the coming show and all the opportunities for study and scholarship were originally why she had wanted to work at the museum. But since she’d been hired, over a year ago, no one had mentioned it, and it was only two years out. Did he imagine she’d stay in the basement for all that time, content and unconsulted?

“Of course,” she said. “I haven’t seen Juliet Goldman or Jewess on the Eve since I was a grad student.” These were both on almost permanent display at the Prado, where, as a student, she’d been given a three-month summer fellowship. She never knew just how much of her CV to remind him of in these conversations where the power dynamics remained inscrutable.

“Oh, those,” he said. “We’ll have them. Bit of concern where to put them. Wallwise. I don’t think we’ll go chronologically, but they’ll need some different backing. Early and all. Very red.”

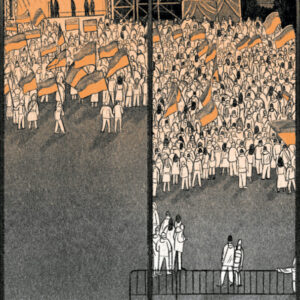

“What are you thinking for themes?” Rachel had been curating the exhibit in her head for months now. Simon would insist, of course, on a thematic organization of his own devising, but for Lurio a chronological display would actually make sense: his fin de siècle affectations, followed by the period of silence and then, almost overnight, his sudden passionate adoption of what he’d been hiding ever since he changed his name from Lurtz: his eastern European Judaism. They could end with the last few works done in Canada after the war. The sequence of Enoch among the heavenly hosts, violent, shattering with Blakeian geometry and color. If these were, as most scholars claimed, the mournful eulogy to a lost world, she didn’t see it. In all of them Enoch, witness to the divine machine, seems struck not by wonder, but rage. Yes, she always thought of Blake; whatever hand or eye dreamed up the world must be monstrous. Enoch confronts the celestial hosts, all wearing capes of swastika red under an oppressive horizon of jutting lightning and glaring orange mountains. It’s supposed to be heaven, but if he believed in it, she couldn’t imagine how else Lurio would fashion hell.

“What are you thinking for themes?” she asked again. For the previous ten seconds, a huge green piece of a caterpillar roll had required the curator’s entire attention.

“Oh, right. Well, it’s early days you know. But probably going with Devotion and Temperament. Inner Storm, Outer Order. The Artist’s Journey. That kind of thing.”

Lurio had been into absinthe and hashish while in Paris, though he quit when it began hurting his health and slowing his output. Still, it was what everyone focused on. The Bohemian excess, the booze, the drugs, the naked muses.

Rachel put down her chopsticks. Here was something she had learned when she started volunteering at NextSteps, a support group for young people trying to leave their ultra-Orthodox communities: Give someone a beautiful particular, and they saw only the ugly generality. She had tried the particular, the peculiar, she had taken Samuel’s hand and led him out of his father’s house. She had tried love. But she had not tried it gently enough. She had believed that the storm of Samuel’s leaving his community, the passion of exodus would protect them in the world. She had not warned him how fast the world could change. One day you could be one of the Haredim, ultra-Orthodox, speaking Yiddish, living in a Brooklyn anachronism of fanatical rigidity, and the next you could have a reform wife in Manhattan, you could be severed from three hundred years of tradition, you could abandon your family, you could shave your beard, you could laugh at the Law, you could be eating a cheeseburger, you could, as he was, be dead. Or you could be Rachel. One day you could save the man you love, with your heart usher him into freedom and stand by and watch as he so badly misunderstands what that means, you could be married, you could be a widow, you could be grieving and then past grief and into what—what is on the other side of grief? Just the silly inanity of daily life: a tasteless curator, a slave to cliché, a man who, where he deviated from cliché, was even worse. For Rachel, there was never an escape from the particular: what kind of Jew wears seersucker?

She asked a question of her own. “Aren’t you afraid of mercury poisoning?”

He was like a sea creature himself. A cuttlefish sweeping along the reef. His face seemed to flash through colors, his cheeks rouged, then went pink, then yellow. There goes his liver, Rachel thought.

He pointed a chopstick at her. “Did you know Lurio’s name was originally Lurtz?”

*

Later, walking back to work, she mentioned the Lurio sketch found in Maine.

“Actually, I’m the one who authenticated it,” he said.

“You never told me.”

“Went all the way up to Maine. To this estate on an island.”

“They’re holding an auction next weekend, right?”

“In Maine,” he said and then whistled the way children do, by sucking in. “How does anything get there?”

Even in the wake of Sam’s death, she could not totally escape the routines of her old life in the city (drinks, brunches, the occasional coffee), and in these situations—although people rarely ask questions of the grief-stricken—she told people that she worked at the Museum of Jewish Art, which she did, but the museum was more than its galleries, and if you have a PhD in Art History and a Masters in Museum Studies, people expect that when you say you work at an art museum that you work with, or near, or in some way in view of, the art.

But Rachel worked in the basement. Beside each painting in the gallery was a small placard with the code that corresponded to her chart and with the number to the phone in her office. If anyone had a question about the work before them, they could call it, and Rachel, sitting in a room three to five floors below them, alone, a little cold, immune by now to the smell of mildew, would answer. Previously the museum had educators on site, in the galleries, available for questions, but no one ever asked them anything except whether they were allowed to take photos of the paintings, to which the educators only had to point to the sign saying no flash allowed. To the museum board, this seemed like a poor allocation of resources; certainly the guards or docents could instruct people on flash usage. Gesturing wordlessly to a sign did not require a staff with PhDs. But when, after culling their ranks and muddying their titles, they moved the “adjunct education and curation staff” down to the basement and made their expertise both invisible and a service you could access with your phone, people began to take advantage. To be fair, after the first hectic weeks of an exhibit’s opening, not many did, but enough to keep Rachel her job, especially since, by the time she was hired, all the others had quit.

So when the phone rang and Jacob asked for her by name, she was surprised, both because he was asking for her personally and because he was asking anything at all. For the most part, men didn’t call the “question line,” and the ones who did didn’t ask questions. Sometimes they were on dates and were having a disagreement about the work with their girlfriends. These phone calls began, “Isn’t it true…” As in “Isn’t it true Diane Arbus was the Anne Sexton of the photography world?” Usually, though, if a man called, it was, by the sound of his voice, an older gentleman who wanted to tell her about the painting. These calls would start with a quiz: “Do you know how many children Lucien Freud fathered?” or “Can you tell me in which massacre Anna Klein was executed?” If she paused, she usually got a chuckle, then a hint. “I’ll give you a clue. It was in Lithuania!” Because the museum monitored call volume and length, Rachel stayed on the line. At first she tried to show that yes, she knew the answers, or address the premise of the statement specifically, or suggest that perhaps this trivia was not quite verifiably correct. But any of this—her knowledge or disagreement—did not go over well, so she just took to playing her own game, acting surprised and mispronouncing as many names as she could, either with syllable emphasis or vowel sound, until the caller became confused or uncertain of the pronunciation himself and stopped talking. Then she said, “Thank you!” more brightly than they expected and hung up.

Women called more often. Usually mildly insane, pill-addled art students who were looking to theorize, to share their revelations, to describe to her something they saw in the painting and, always—and this is what made their theorizing different from the men’s—to ask her if she saw it too. They were all in some kind of pain and they were all a little afraid. They believed she was perched in a security booth and was watching them through the cameras. When they asked, “Can you see me?” she learned to say yes, to tell them they were beautiful, to agree, through her own tears, that, “Yes, yes, looking at the painting this way does make it feel better.” As best she could, she cleared her mind in these conversations. She had no idea how to take care of another’s pain; her track record here was perfectly miserable. Pain was not an emotion. If they were feeling pain, she could not tell them otherwise. She had tried that at first with Sam’s sister, Rivkah; afterward, with Samuel, she had been more careful. Both strategies had been wrong. The best thing was to show these people that the rest of the world was not so bad, the rest of the world was beautiful, well composed, full of light, full of love. She knew she was lying, but only about herself. It was the least she could do.

When Jacob called, she answered the basement phone, and the ringing continued. This was a dream she had now, trying to answer a phone that wouldn’t stop ringing. But it was her cell phone that was ringing, and she answered it this time, as she always did now, even though she didn’t recognize the number. He told her why he was calling, how he’d met Baer and what Baer had asked him to do. He was polite, but not apologetic. When she agreed immediately, without him needing to convince her or spell his last name, he sounded surprised. She also said she’d drive.

“Great,” he said. “I’ll bring CDs.” It was only a slightly stupid thing to say.

After he hung up, she called Baer. She thanked him for finding Jacob. She said, “Can you do dinner tonight?” Silence, static, a fault on the line: he was on his cordless phone, shaking his head. “Uncle?” she said. He was her cousin, but she called him uncle.

He barely muttered, “No.” “Nights are not good,” he said.

She waited for more. Nothing. “I can bring something over? I can get takeout?”

Again he said, “Nights are not good.”

“Tomorrow then? How about lunch?”

“At the cafeteria?” He sounded almost hopeful. There would be other old ghosts there. He despised them all. But he could, as he usually did, pretend that she was his granddaughter.

“Tomorrow,” Rachel said. “Tomorrow, the cafeteria, noon.”

Baer assented and the line went dead. She checked her watch. Two in the afternoon. Above her, she could almost feel the museum’s emptiness. The tread of the guards sweeping through the galleries, the hum of the central air, the golden light falling unwitnessed through the great glass windows in the lobby. She had the sensation, strange, but not for the first time, that the silence originated in this room, with her. It wasn’t the slumberous silence of above, but sudden and dull, like in an airplane, the muffled quiet of altitude. There was something to be heard, but she couldn’t hear it. Her dreams of late had all been like this, trying to pack without a bag or leave the house without her keys, trying to read without her contacts. Clearly, her absurd office dredged its barrenness from her. It would be good to get away this weekend. To see the Lurio sketch. To try to force an accounting. Against a wider perspective, it was a simple enough thing to make right, and once she did it, her life would begin to change.

In the meantime, she could scream. She could accumulate clothes with colored feathers attached; she was thirty-two, in the first months of Trump, and grieving—hysteria was expected, but she felt terribly sane. Which might be a problem this weekend, where they were going. She would need to practice at neurosis. Tomorrow perhaps, she could ask the curator out for a drink and then spill wine on his suit. She would stare at the stain and say, I’ve touched the back of the page where Lurio’s pencil scratched. She’d say, Nothing goes unmarked. She could say, By now your thighs are damp. She would slap his soft and sallow, stupid face and sneer, What kind of name is Simon?

*

As usual, Baer was at the cafeteria before she was. In the past she had tried getting there early, fifteen, twenty, thirty minutes, but he was always already there. She saw him too rarely, she knew that, but he would not allow her to visit his apartment, and she had the feeling that to meet her out, to make a noon appointment, was a cause of significant anxiety for him. He would arrive hours early, just to make sure that he could arrive at all.

She saw him through the glass of the front window, and then through the glass of the door; he was facing the street, staring out over his coffee. His eyes were unblinking and vacant. He looked old, he looked slack, he looked like someone failing to recover from a shock, he looked like everyone else in the cafeteria.

There used to be many similar places on the Upper East Side where, just after the war, the Jewish refugees and immigrants, the lucky ones who survived by coming over before the catastrophe and the unlucky ones who did not and survived anyway, would meet to chat, to eat stewed prunes, or chicken soup, to read the Yiddish papers. This one was the last of its kind. It smelled of grease and soap. The food was heavy, generally tasteless, mostly gray. Everything was available with a side of jarred horseradish.

She stepped inside, the bell on the door chimed, a few people turned to watch her enter—she was about sixty years too young. They squinted and stared. The sheer human devastation witnessed by the half-dozen people pretending to eat their lunch in here could nullify any legitimate emotional experience within twenty city blocks. She felt, as she always did, the sickening throb of self-disgust: against theirs, her sorrow was nothing, her guilt was nothing, her grief was a joke. She could not even relate to their world with the communal righteousness of a fellow Jew; her parents did not practice and she had come to her religion intentionally in college. Intellectually she knew that grief masqueraded as unwarranted anger, but she still felt the shame of her resentment. You people don’t own loss, she thought, looking around. And it’s true, they didn’t. Loss owned them, and in this she felt another permutation of her grossness—she still coveted her wound, she clung to it as to Samuel himself.

When they first met at NextSteps, when she first saw him looking up from the handout she had made on dating in the secular world, when she saw his smile run aground as he raised his hand to ask a question in an impossible Yiddish accent, she had known the world would not accommodate someone who entered it so uncertainly and she had reached out to ease his passage, yes, but also to feel the vicarious tremor of his awe. She had opened her heart even as she thought, Here is heartbreak. You only had to spend a single afternoon with Samuel, with his sister Rivkah, with any of the Haredim looking to break free of their communities to know that their pain would never wholly disappear. At the time it seemed perfectly melancholy, letting her life be defined by another’s sorrow, but now, confronted by her own loss and then seeing it dwarfed by the cataclysm of incurable grief in this room, she could only think of Lurio’s Enoch apprehending the cosmic revelation with his perfect human disgust.

Baer saw her and he smiled and waved. She swept into the room and took his hands and kissed his cheeks—one, two—as they did in her family. She sat and tried to exchange pleasantries. He wasn’t really interested. He was looking over her shoulder and fidgeting with the handle of his coffee mug. She got up and ordered them some soup. It was both easy to eat and not too hot.

“Uncle,” she said, “tell me the truth. How are things?”

“I’m fine,” he said. “I’m always fine.”

“I’ve talked to the people at HUD and at Yad Vashem. I’ve got some apartments for you to look at.”

“Can I afford them?”

“I don’t know. Did the social worker call you back?”

He shrugged. The soup was ready. They called her name and she went up and got it. Baer cupped his hands around the bowl, pulled it close to his chest, and hunched forward as he ate.

“Do you need any groceries?” Rachel asked. “I can get groceries.”

“It’s not a problem,” she said. “We can go after lunch. I’ll have time.”

He didn’t look up from his soup. “That boy, Jacob, he left me herring. And then brought bagels. Apparently I am that pathetic. To see me is to know.”

“I’m sure he was just being kind. He was probably just worried about you. We all are.”

“Listen to her,” Baer shouted into his soup. “She’s a widow. Her husband was a suicide. And she’s worried about me?” He dropped his spoon and covered his mouth. “I’m sorry,” he said in a whisper. “You know my moods.” He pointed at an old woman sitting in the corner reading the paper. “Sophie also has to move. And she can hardly walk. She needs a new wheelchair. She came over here with no one, she still has no one. She has had no one since she was six years old.”

Rachel looked down at her soup and then up at Baer, at Sophie. She watched the woman slowly begin to fold the paper.

“My point is that there are people who deserve help more than me,” Baer said.

“Uncle, when you say ‘deserve,’ what could you possibly mean?”

“Nothing,” Baer said. “Gornisht.”

They sat in silence for a few minutes. Baer called over to Sophie, “Come meet my granddaughter!” but she just waved.

“Are you ready for the weekend in Maine?” he said to Rachel.

“Not really,” she said. “Is Alex Baruch as much of a charlatan as everybody claims?”

“How should I know? Who cares?”

“How can you say that?”

He reached down into his lap for his napkin and dabbed his chin. “Maine,” he said. “I’ve never been.”

“Rednecks with boats.”

“Stop,” he said. “Some sea air will be good for you.”

“An abandoned sanitarium on the coast? Sounds creepy.”

“Stop.”

“Who even still has a sanitarium? Will there be lepers?”

“Lepers do not go to sanitariums.”

“Of course not,” she said. “Because there are no more lepers. Just like there are no more sanitaria.”

Baer grabbed the arms of his chair and began to stand. “Come on, granddaughter,” he said. “Let’s go bother Sophie.”

*

Before she went home, Rachel went to the cemetery.

She waited until after six. At five, the cemetery was still congested like everywhere else: crowds on their way home, stopping to do their grieving. People stood as if they were waiting for the subway, or sat chatting by graves, bags of groceries at their feet, cell phones out and playing music as if they were at home in the kitchen with their loved ones. Sometimes this community, its blunt everydayness, made her feel better, and other times it was crushing. A lie they were all telling themselves, sitting in grass, mumbling to nothing.

It was almost seven when she arrived. Dusk, and with it a wind out of the east and the smell of the river, rich, domestic, a smell from childhood: the wet, mulched yard after a thunderstorm. They’d be closing the gates soon to keep teenagers out. Already, on her way in, she saw four of them leave, heads down, hoods up despite the heat, backpacks on badly, only one strap in use and upside down. It was desperate, and she felt, as she always did, a pang of tenderness for the desperate. They bristled with anger and masculinity—their shoulder-rolling walk, their hands in pockets, the one who, seeing her, turned aside to spit—and yet they couldn’t even carry a backpack. She had smiled and said, “Hi” as they passed, and they didn’t respond but they slowed, as if surprised, as if on the verge of speech, like they might actually have something to tell her, before hustling out of the graves and into the summer street.

The cemetery was divided in two by a windbreak of giant elms. Passing through them on the path, she always felt like she was back at college, walking down the quad from the library to her dorm. In those days, late at night when the elms’ leaves silvered under light from the globes of lamps, when the whole quad, the grass and leaves and bushes shimmered as if with frost, she had believed, had known even, that she was finally entering the life she had always imagined, approaching its threshold, walking a line that with one more step would reveal full-formed the sensual world, the sensual life, her own future body and soul in total clarity. Here in the cemetery, the elms triggered a shiver of this old pleasure, though in feeling it she was in fact experiencing its opposite. These trees, this graveyard, her walk among them mocked that memory. Her beautiful life, her possibility and longing, the things she had to say to the world and the love she had to give, had come to this. Which was what she was thinking when she broke through the windbreak and stepped into the back half of the cemetery and thought for a moment that she was lost, that she’d taken a wrong turn and entered a construction zone or an area of intentional refurbishment.

At her feet: broken stones, flowers torn apart, everywhere slurs sprayed in candy pink paint. Her hand was over her mouth. She was off the path and scrambling among the graves, among the petals, the mourners’ stones kicked into the grass, where she also was on her knees, rubbing at random at names—GREEN, HERSCH, KOPPLEMAN—trying to rub the paint off them, the KIKE and JUDEN and YID and the swastikas and iron crosses and slogans of ADOLPH LIVES and ZYKLON-B, all in neon pink balloon letters. Like a joke. Like the scribbled notes of teenage girls in the margins of a notebook. She was laughing. And swearing. She was a crazy person in the park. And then she was on her feet again. There must be somebody to alert. Or more importantly: somebody to protect. She looked over her shoulder. The teenagers were gone, but there might be a mourner. Some poor soul wandering in after work to say a Kaddish. Someone who should not stumble into this, who should not have to see the grave of her loved one defaced. She turned, wildly, again. Because of how Samuel died, the rabbi said she should not rend her clothes. She was rending them now. She slipped and stood again and her skirt caught on the row of tended rosebushes lining the path. She saw someone on the other side, near the gate. She could stop them from looking. She took off her shoes. She ran toward her.

__________________________________

From The Tavern at the End of History by Morris Collins. Used with permission of the publisher, DZANC Books. Copyright © 2026 by Morris Collins.